Many people remember the solar storm of May 2024, which saw auroras spread into areas that very rarely get to see them. But while millions were watching the skies, astronomers were watching the Sun itself.

For more than three months, a pair of observatories, positioned on either side of the Sun, managed to track an active region on the solar surface almost continuously from birth to death. That marks a new record, and the achievement could help improve predictions of space weather.

Related: The Most Violent Solar Storm Ever Detected Hit Earth in 12350 BCE

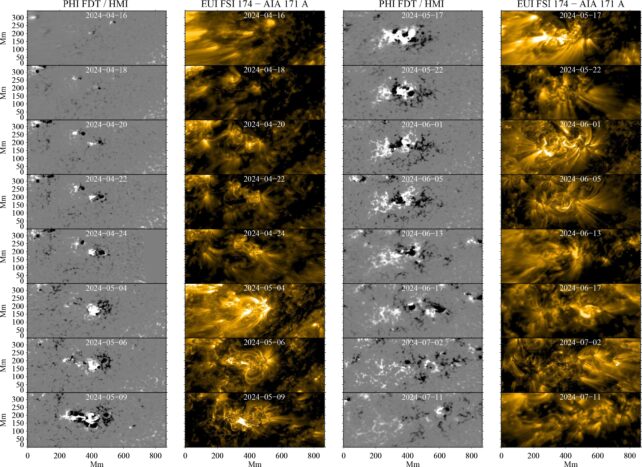

This active region, designated NOAA 13664, was born on the far side of the Sun on 16 April 2024, before rotating to face Earth in May, triggering the strongest geomagnetic storms in decades. It rotated out of view on 18 July 2024, and the region seemed to have calmed down by the time it became visible again.

Astronomers managed to observe NOAA 13664 almost non-stop for those 90-odd days in between, losing it only briefly between April 26 and 29.

"This is the longest continuous series of images ever created for a single active region," says Ioannis Kontogiannis, a solar physicist at ETH Zurich in Switzerland. "It's a milestone in solar physics."

Normally, astronomers only get about two weeks at a time to study active solar regions – the Sun rotates once every 28 days, meaning any given region is only visible from Earth for half that time.

But in this case, two spacecraft managed to watch it from different positions simultaneously. The Solar Orbiter, launched by the European Space Agency (ESA) in 2020, was observing the far side of the Sun when NOAA 13664 was born, while NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory maintained its vigilance from Earth orbit.

Thanks to these two eyes in the sky, researchers were able to watch how the active region's magnetic fields developed over time, and how those changes drive solar activity.

Solar storms don't just bring us stunning light shows – they can damage satellites, electricity grids, and communication systems. That's why it's so important to better understand them and predict when they might strike.

The research was published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.