Scientists have confirmed in the largest study of its kind that bacteria, not fungi, are the major culprit in auto-brewery syndrome, a rare medical condition where people become intoxicated after eating, despite not consuming any alcohol.

Analyzing stool samples from 22 patients diagnosed with ABS, and their unaffected household partners, researchers identified two common bacterial species that are more abundant in people with the syndrome, reinforcing the findings of a 2019 study.

Cases of auto-brewery syndrome are rarely diagnosed, and there is no consensus on how to treat the condition, so even though the study is small, it represents a meaningful number of patients who have been rigorously tested for ABS – and whose gut bacteria produced high levels of ethanol when cultured in lab experiments.

Related: Mysterious, Rare Syndrome Causes The Human Body to 'Brew' Alcohol

"Many patients will visit multiple medical centers only to be dismissed as surreptitious drinkers and leave without a diagnosis," the team, led by infectious disease expert Elizabeth Hohmann of Massachusetts General Hospital and gastroenterologist Bernd Schnabl of the University of California San Diego, writes in their published paper.

The surging levels of ethanol in their bodies often cause liver damage, not to mention serious social, family, and legal problems.

The new study came about after microbiologist Jing Yuan of Beijing's Capital Institute of Pediatrics was flooded with calls from patients desperate to be tested for ABS.

It was 2019, and Yuan (who was not involved in the current study) had just published research implicating the bacterium Klebsiella pneumoniae as the likely cause of ABS rather than commensal forms of yeast as some suspected. She referred the callers to Schnabl, who began recruiting patients for a follow-up study.

Comparing gut microbes from ABS patients to those of people they live with, the new study effectively controlled for environmental and dietary factors known to influence gut microbiomes.

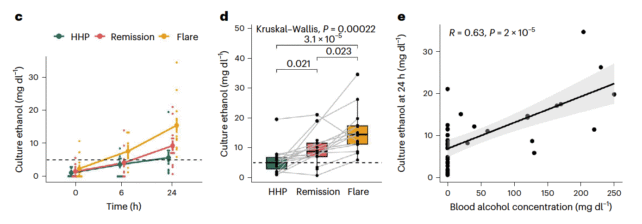

Schnabl and colleagues found that bacterial cultures from patients experiencing 'flare-ups' – symptoms of intoxication – produced more ethanol than microbes from those in remission or from household members unaffected by the condition. This correlated with blood alcohol levels measured during the same period.

K. pneumonia and Escherichia coli, two bacterial species known to produce ethanol, were both more prevalent in ABS patients, and E. coli was particularly overabundant during ABS flares.

One patient's symptoms markedly improved after he received two stool transplants from an unaffected donor to reset his gut microbiota. The man remained in remission for more than 16 months after the second dose, and his family says his normal behavior has "essentially returned".

The findings suggest relief for ABS patients might lie in promoting or introducing, through dietary changes, stool transplants or probiotics, other strains of gut bacteria that readily metabolise ethanol. Although Schnabl doesn't rule out the possibility that some cases of ABS may be caused by fungi or yeast.

Potential treatments may also be able to target bacterial genes involved in metabolic pathways that the researchers found were more active during periods of remission, helping to resolve symptoms.

The team also notes that ABS patients in this study had "extreme" imbalances in their gut microbiomes. Other studies have reported low levels of ethanol production in patients with diabetes and implicated ethanol-producing gut microbes in fatty liver disease, the most common liver disease globally.

"This raises a broader question of how prevalent gut microbial ethanol production is in the general population and how widespread the pathological implications could be," Schnabl and colleagues write.

"In addition, our study highlights the importance of the gut microbiome and microbial metabolites to human health," they conclude.

The study has been published in Nature Microbiology.