As we get older, chemical marks on our DNA slowly shift. Now, a study reveals this 'drift' in gut stem cells is fueled by inflammation and disrupted cell signaling, and it may help explain why our risk of colorectal cancer rises with age.

The international team of researchers has called this process Aging and Colon Cancer-Associated (ACCA) drift, and it involves shifts in DNA methylation that can 'switch' genes on or off without altering the DNA – called epigenetic changes.

In this case, the drift leads to the gradual silencing of genes that help suppress tumor formation, allowing cancer risk to build up in more and more cells across the gut, long before tumors appear.

Related: Just 3 Days of Binge Drinking Triggers Rapid Gut Damage in Mice

"We observe an epigenetic pattern that becomes increasingly apparent with age," says molecular biologist Francesco Neri, from the University of Turin in Italy.

Starting with what was known – that epigenetic drift has been linked to cancer, and that colorectal cancer risk rises with age – the researchers studied tissue from both healthy human colons and colon cancer tumors, looking for common methylation patterns.

They found similar patterns of gene silencing in older individuals and in cancerous tissue, suggesting a common underlying process.

Further experiments on mouse models and organoids (mini-guts grown in the lab) helped the researchers establish what was driving the drift and how it was spreading, and confirmed that it was unique to the intestines.

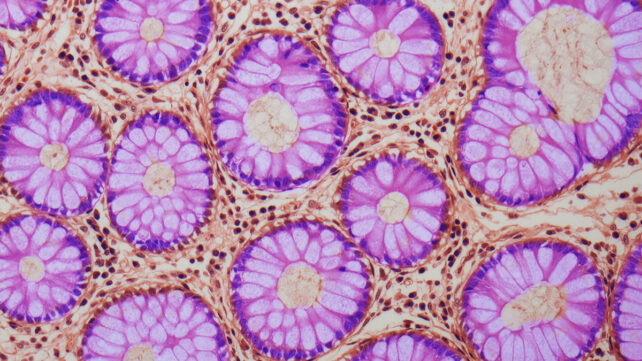

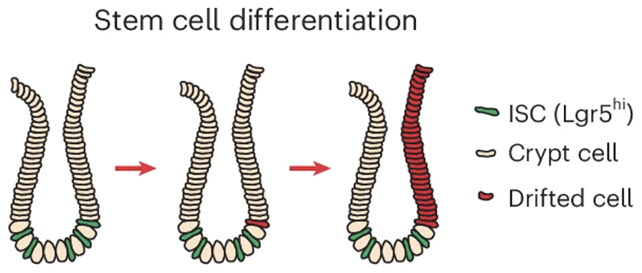

The focus was on intestinal crypts, small pockets in the gut lining that house stem cells that renew the intestinal lining. Experiments showed that ACCA drift originates within these stem cells and then expands as crypts divide and spread.

Here's what's happening: increased inflammation, reduced growth signaling, and reduced iron levels in intestinal crypt stem cells combine to disrupt the processes that tidy up methylation, leading to genes being deactivated – in a way that potentially allows cancer to develop.

"Over time, more and more areas with an older epigenetic profile develop in the tissue," says molecular biologist Anna Krepelova, from the University of Turin. "Through the natural process of crypt division, these regions continuously enlarge and can continue to grow over many years."

"When there's not enough iron in the cells, faulty markings remain on the DNA. And the cells lose their ability to remove these markings."

As stem cell-driven crypts divide and multiply, patches of tissue with older, cancer-prone epigenetic profiles gradually expand. This creates more unhealthy pockets throughout the gut over time.

Inflammation, iron imbalance, and lower growth signaling can accelerate epigenetic drift, meaning the aging process and increased vulnerability to cancer can happen earlier in the gut than previously thought.

These danger zones will vary between people, as does cancer risk, but now we know more about how colorectal cancer gets more opportunities to start as we age.

Encouragingly, in organoids, the researchers were able to slow and even partially reverse epigenetic drift by boosting iron uptake or restoring specific cell growth signals.

"This means that epigenetic aging does not have to be a fixed, final state," says Krepelova. "For the first time, we are seeing that it is possible to tweak the parameters of aging that lie deep within the molecular core of the cell."

The research has been published in Nature Aging.