Scientists in Japan have discovered a previously unknown giant virus, offering new insight into this enigmatic category of viruses – and possibly also into the origins of multicellular life.

The virus was found infecting an amoeba in a freshwater pond near Tokyo, the researchers report. They named it "ushikuvirus" after the pond, Ushiku-numa, located in Ibaraki Prefecture.

Giant viruses were largely overlooked during the first century of modern virology, with initial discoveries often misidentified as bacteria due to their size. Yet while we barely knew they existed until recent decades, we've since learned giant viruses are all around us.

Related: Hundreds of Mysterious Giant Viruses Discovered Lurking in The Ocean

Viruses in general are considered the most abundant biological entities on Earth, and some of the most perplexing. Little is known about the evolutionary history of viruses, and there is still ambiguity about whether they qualify as living organisms.

Even if they are not living, viruses clearly wield enormous influence over all forms of life, including us. That includes not just hijacking a host's cells and causing illness, but also occasionally meddling in its evolution.

Viruses can facilitate horizontal gene transfer among living things, and some – known as retroviruses – insert their DNA into the genome of host cells. If that happens in a host's germline, viral DNA can be passed on to its offspring.

In fact, ancient retrovirus remnants now comprise up to 8 percent of the human genome, which has its perks. Retroviral DNA might have given early vertebrates the ability to make myelin, and it was key for the evolution of the placenta.

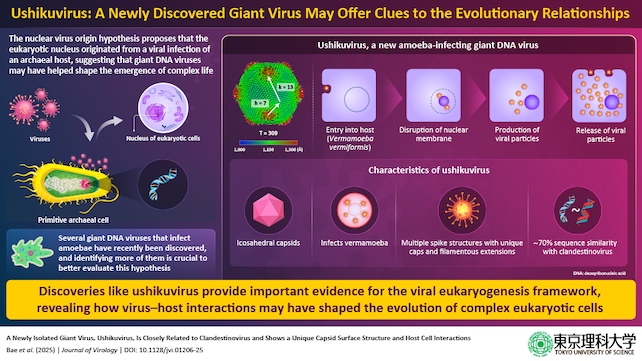

Much earlier, viruses may have sparked an even bigger, more mysterious innovation: the evolutionary leap from prokaryotes, or single-celled organisms, to eukaryotes, or multicellular organisms.

Eukaryotic cells typically have a membrane-bound nucleus, representing a "chasm in design" from their nucleus-free prokaryotic forebears. It's unclear how such a dramatic change occurred, but one intriguing theory suggests that nuclei were a gift from viruses.

Known as viral eukaryogenesis, this idea was first proposed in 2001 by Masaharu Takemura, a molecular biologist at the Tokyo University of Science. He suggested the nucleus of eukaryotic cells arose from a large DNA virus, like a poxvirus, that infected some prehistoric prokaryote.

Instead of causing trouble, the virus made itself at home in the cell's cytoplasm, eventually acquiring important genes from its host and gradually transitioning into a cellular nucleus.

This theory gained traction with the 2003 discovery of giant viruses containing DNA, which form structures called "virus factories" inside host cells. These factories are sometimes enclosed in a membrane and tend to look and function a lot like the nuclei of eukaryotic cells.

Scientists have since found a variety of these giant viruses, including species in the family Mamonoviridae and the closely related clandestinovirus, which infect certain types of amoebae. Giant viruses are highly diverse and difficult to isolate, though, so a new find like ushikuvirus is a big deal.

Takemura is still investigating viral eukaryogenesis a quarter century after he introduced the idea, and was part of the team that identified and described ushikuvirus in the new study.

"Giant viruses can be said to be a treasure trove whose world has yet to be fully understood," Takemura says. "One of the future possibilities of this research is to provide humanity with a new view that connects the world of living organisms with the world of viruses."

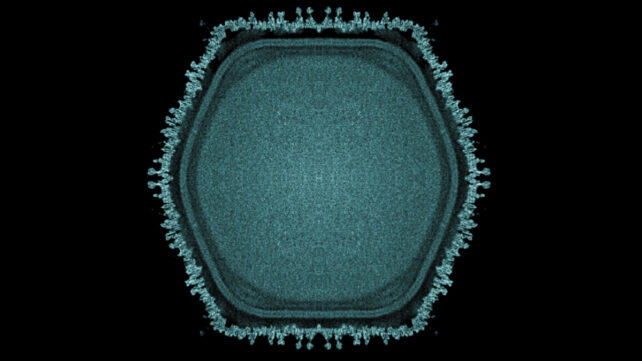

Ushikuvirus infects amoebae known as vermamoeba (Vermamoeba vermiformis), a habit it shares with clandestinovirus; while its shape and spiky capsid surface resemble those of medusaviruses.

It also stands out from other giant viruses, however. It forces its host cells to grow abnormally large, for example, and its capsid spikes have unique caps and fibrous structures.

Rather than preserving a host cell's nucleus and replicating inside, as clandestinovirus and medusaviruses do, ushikuvirus instead forms a viral factory and destroys the host's nuclear membrane.

These similarities and differences can be vital clues, helping scientists piece together the evolutionary history of giant viruses. Takemura and his colleagues hope to learn how and why these viruses diversified so much, as well as what role they played in the rise of eukaryotes like us.

"The discovery of a new Mamonoviridae-related virus, 'ushikuvirus,' which has a different host, is expected to increase knowledge and stimulate discussion regarding the evolution and phylogeny of the Mamonoviridae family," Takemura says.

"As a result, it is believed that we will be able to get closer to the mysteries of the evolution of eukaryotic organisms and the mysteries of giant viruses," he says.

The study was published in the Journal of Virology.