Just as Earth's skies can be darkened by cloud and smog, the oceans too can be shrouded in darkness.

These prolonged periods of darkness aren't just passing shadows; they can take over parts of the ocean for months, with devastating effects on the ecosystem below.

Now, scientists have developed a framework for understanding a concept they call 'marine darkwaves' – temporary, but potentially disastrous events that can severely impact light-dependent marine life.

Related: Mysterious 'Dark Oxygen' Discovered at Bottom of Ocean Stuns Scientists

"Light is a fundamental driver of marine productivity all the way up to the upper food chain, yet until now we have not had a consistent way to measure extreme reductions in underwater light, and this phenomenon did not even have a name," says marine scientist François Thoral of Waikato and Canterbury Universities in New Zealand.

"Marine darkwaves allow us to identify when and where these events occur, shedding new light on a critical but often overlooked phenomenon."

For many years now, scientists have tracked a phenomenon called ocean darkening – a long-term, gradual drop in water clarity that limits the amount of light that can penetrate the water column associated with declining kelp forests, delayed phytoplankton blooms, stressed coral reefs, and shrinking seagrass meadows.

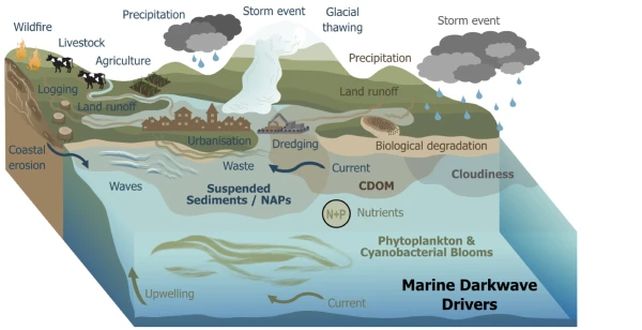

But that's a slow, steady change that has been marching on for decades. It doesn't include the short, intense, episodic periods of darkness driven by storms, algal blooms, and sediment deposition, often following natural events such as wildfires, cyclones, and mudslides.

These intense periods of darkening – the marine darkwaves – can be just as damaging as the slower long-term dimming, the researchers say.

The new work gives scientists a tool for identifying these shorter-term events by adapting the frameworks they use to detect other episodic ocean events, such as marine heatwaves and cold spells. They used this to set the defining parameters for a marine darkwave, such as minimum duration, the degree of light loss relative to a seasonal baseline, and the depth at which the loss occurs.

The team then applied the framework to 16 years of underwater light measurements previously collected from the California coast and 10 years of data from New Zealand coastal sites in the Hauraki Gulf (Tikapa Moana). These measurements were taken at depths of 7 and 20 meters. They also applied their framework to 21 years of satellite-sensing of seabed light in the waters off New Zealand's East Cape.

Between 2002 and 2023, between 25 and 80 marine darkwaves were detected off East Cape, typically lasting between 5 and 15 days on average. The longest event persisted for 64 days.

Many of these events were associated with storm conditions, including Cyclone Gabrielle in 2023. Coastal moorings in the Firth of Thames, a bay in the north of New Zealand, also recorded other storm-related darkwaves. Other causes included topsoil pollution from deforestation, wildfire runoff, and plankton blooms, and potentially dredging and coastal construction work.

In extreme cases, at the peak of some darkwaves, the degree of dimming can make for literally some of the darkest days these patches of ocean see at any given time of the year.

The paper did not quantify the effects this had on marine life directly, but it did point to other, previously published works showing that a drop in light levels can affect entire ecosystems, from kelp forests to macroalgal communities to jellyfish.

"Even short periods of reduced light can impair photosynthesis in kelp forests, seagrass, and corals," Thoral says. "These events can also influence the behaviour of fish, sharks, and marine mammals. When darkness persists, the ecological effects can be significant."

Further work will be needed to identify different types of events – a phytoplankton bloom and a sediment dump may affect light quality in different ways – and to quantify the level of habitat damage that can be attributed to these marine darkwave events.

However, now that the basic framework is in place, future work has a solid basis to build from.

"Coastal ecosystems are increasingly exposed to storm-driven sedimentation and higher climate variability," says coastal scientist Chris Battershill of the University of Waikato.

"Marine darkwaves help us understand when these systems are under acute stress. This framework will be invaluable for iwi and hapū, coastal communities, and marine conservationists who need accurate information to guide decision making."

The research has been published in Communications Earth & Environment.