An enzyme known to regulate inflammation throughout the body has now been found to also act as a master switch for genes associated with neurodegeneration, with broad implications for Alzheimer's disease and brain aging.

Researchers from the University of New Mexico and the University of Tennessee conducted a series of experiments on human tissue cultures, measuring the effects of knocking out an enzyme called OTULIN.

When OTULIN activity was blocked in cells, the researchers found that the level of a protein closely linked to Alzheimer's disease called tau was reduced. When the gene producing OTULIN was removed completely, tau disappeared – it was no longer being produced at all.

What's more, this tau removal didn't seem to affect the health of the neurons.

Related: Switching Off One Crucial Protein Appears to Reverse Brain Aging in Mice

Neurons from a donor with Alzheimer's were compared with neurons grown from stem cells taken from healthy donors, which showed that both OTULIN and tau were more abundant in the neurons affected by the disease.

"Pathological tau is the main player for both brain aging and neurodegenerative disease," says molecular geneticist Karthikeyan Tangavelou, from the University of New Mexico.

"If you stop tau synthesis by targeting OTULIN in neurons, you can restore a healthy brain and prevent brain aging."

The idea of disrupting or removing OTULIN as a treatment to slow brain aging is unfeasible, at least for the foreseeable future. Both the enzyme and tau play key roles in our body's functions.

As the researchers point out, any kind of OTULIN restriction would need to be carefully managed in order to avoid causing damage elsewhere.

"We discovered OTULIN's function in neurons," says Tangavelou. "We don't know how OTULIN functions in other cell types in the brain."

That said, these are interesting and rather surprising findings that could prove incredibly useful in future research. One of our best chances at treating Alzheimer's seems to be in removing the harmful protein build-up that comes with it. Now we have a new route through which that might be done.

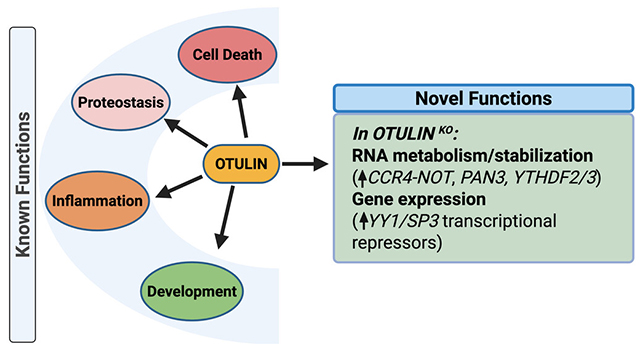

The team went further, using RNA sequencing to look at the broader effects of OTULIN removal. Not only was tau production stopped, but the activity of dozens of other genes was impacted, too.

These genes were mostly associated with inflammation, the researchers found, suggesting that OTULIN can play a key role in neuron stress, and wear and tear on the brain when it's not operating as it normally should.

Again, this all has to be tested in animal and human models, but scientists now potentially have another target to aim at when developing treatments for Alzheimer's and other related diseases. What's more, it's not the only enzyme that researchers are paying close attention to.

We know that one of the jobs that OTULIN does is helping to regulate the clearing away of waste from cells – including tangles and clumps of excess proteins such as tau – and when it malfunctions, problems start to pile up.

"This is a great opportunity to develop many projects for further research to reverse brain aging and have a healthy brain," says Tangavelou.

The research has been published in Genomic Psychiatry.