In Earth's highly radioactive hotspots, life can get pretty strange – from fungus that seems to thrive to an explosion of vertebrate diversity in the absence of human interference.

A different story has emerged at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station in Japan. There, in the torus room below the reactor, a community of microbes has been quietly nesting in the dark ever since an earthquake flooded the facility with seawater in 2011.

Elsewhere in the world, lifeforms exposed to radiation tend to develop subtle new traits. What makes the Fukushima microbial communities so remarkable, scientists found in 2024, is that they appear to have no special adaptations.

Their story is one of endurance facilitated by a set of traits that allow them to survive in conditions where other organisms might fail.

Related: Chernobyl Fungus Appears to Have Evolved an Incredible Ability

The Fukushima nuclear accident of March 2011 was the direct result of an underwater earthquake off the coast of Japan that sent a tsunami surging into the power plant on the coast of the town of Ōkuma, in the Fukushima Prefecture, flooding it with water and triggering core meltdowns.

The town was evacuated immediately and has since remained largely depopulated, with only limited numbers of residents returning in recent years alongside scientists and cleanup crews.

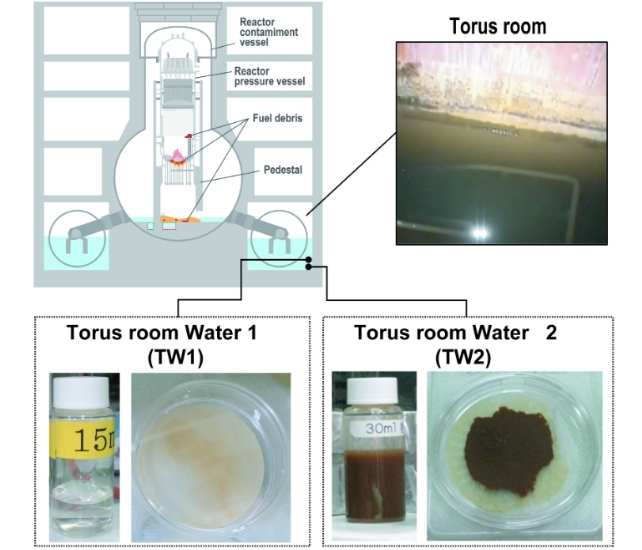

But inside the reactor buildings, a new problem emerged. Huge amounts of radioactive water accumulated, and in that water, engineers noticed, were growths that looked a lot like microbial mats.

This is not an idle concern. Decommissioning a nuclear power plant is a complicated and decades-long project that, as scientists found after the 1979 Three Mile Island nuclear accident, can be seriously hampered by microbes, which can accelerate metal corrosion and even reduce visibility in water, complicating cleanup operations.

With this concern in mind, a team of scientists led by biologists Tomoro Warashina and Akio Kanai of Keio University in Japan sampled the highly radioactive water of the torus room – a safety chamber beneath the reactor, designed to absorb steam pressure – and ran the samples through genetic sequencing to identify which microbes were present.

Based on prior studies, and microbes found at sites like Chernobyl, they expected to find a swathe of radiation-resistant species, such as Deinococcus radiodurans – one of the most radiation-resistant organisms known – and Methylobacterium radiotolerans.

Instead, they found something surprising. The dominant organisms belonged to the genera Limnobacter and Brevirhabdus – chemolithotrophic bacteria normally found in marine environments where they oxidize inorganic compounds such as sulfur and manganese. A smaller proportion of the bacteria belonged to the Hoeflea and Sphingopyxis genera, which oxidize iron.

The water itself was highly radioactive, but compared to communities found elsewhere, these species had no special radiation resistance. This suggests that the level of ionizing radiation was not sufficient to prevent the growth of the microbial communities over time in a way that promoted survival of radiation-resistant species at the expense of others.

There's one other crucial piece of the puzzle. The microbes were likely living in biofilms – 'mats' of microbes protected by a slimy extracellular matrix, which may have conferred a level of protection against the ionizing radiation in the chamber, the researchers said.

This is worth paying attention to. Biofilms can accelerate metal corrosion, and if biofilm-building microbes are the ones most likely to survive in radioactive waters, then that presents a predictable complication to consider during nuclear power plant decommissioning.

And these bacteria didn't need any biological tricks to do it, either. Radiation didn't force life into strange new survival strategies here or require extremophile abilities; rather, it created an extraordinary environment where quite ordinary life could nevertheless eke out an existence.

That's quite marvelous, even if it now poses a problem we can't afford to ignore.

The research was published in Applied and Environmental Microbiology.