The high-fat, low-carb ketogenic diet has been growing in popularity in recent years, following claims of rapid weight loss. But new research in mice suggests there are some seriously concerning side effects too.

"I would urge anyone to talk to a healthcare provider if they're thinking about going on a ketogenic diet," says physiologist Molly Gallop, lead author of the study.

Led by a team from the University of Utah, the research found that while mice on a keto-like diet did indeed lose weight, they also developed fatty liver disease and showed signs of poorer blood sugar regulation.

These findings have yet to be replicated in humans, but they suggest that the biological effects that the keto diet is designed to trigger may not all be beneficial to the body's metabolism.

Related: We Were Wrong About Restrictive Diets, Decades of Research Says

"We've seen short-term studies and those just looking at weight, but not really any studies looking at what happens over the longer term or with other facets of metabolic health," says Gallop.

The keto diet gets its name from ketosis, the metabolic state that it triggers. This means your body starts burning more fat as fuel, rather than glucose, and inducing it requires eating foods with increased levels of fat and reduced levels of carbohydrates.

In the new study, the researchers analyzed mice on four different diets for at least nine months: a high-fat (Western-style) diet; a very-high-fat, low-carb (keto-style) diet; a low-fat, high-carb diet; and a low-fat diet with protein levels to match the keto-style diet.

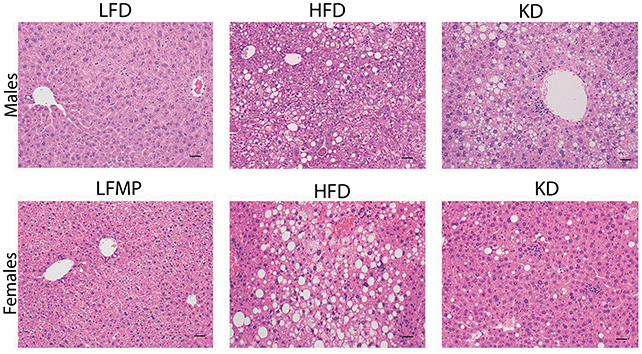

Compared to the standard high-fat diet, the mice on the keto diet gained significantly less weight. However, the male mice on the keto diet developed fatty liver disease and were shown to have impaired liver function – signs of metabolic disease.

"One thing that's very clear is that if you have a really high-fat diet, the lipids have to go somewhere, and they usually end up in the blood and the liver," says University of Utah physiologist Amandine Chaix, senior author of the study.

Both male and female mice on the keto diet had low levels of blood glucose and insulin, within the space of two or three months. Further analysis showed that this was a problem with regulation – cells in the pancreas weren't producing enough insulin.

While further research is needed to understand the mechanisms at work – and to determine why the liver problems depended on sex – the team suggests that an overload of fats (or lipids) in the blood are stressing pancreas cells and impairing insulin production.

There is some positive news: blood sugar regulation returned to normal in mice taken off the keto diet, indicating that these issues can be reversed.

The ketogenic diet was originally developed for epilepsy, and is still used to treat it today. Ketosis mimics some of the metabolic effects of starvation, forcing the body to switch to using fat instead of sugar for fuel. Researchers suspect this low sugar availability also reduces seizures.

When it comes to other applications of the diet, this study and previous research show that the increased risk of other health problems may not be worth the potential upside of weight loss.

The research has been published in Science Advances.