Osteoporosis is a bone-weakening disease that afflicts tens of millions of people, and much-needed new treatments could be on the way after researchers discovered a key mechanism behind how exercise strengthens bones.

Knowing this previously hidden process means scientists might be able to adapt it to combat the bone fragility caused by osteoporosis. While it's been well established that exercise boosts bone health, until now it wasn't fully clear how.

The researchers, led by a team from the University of Hong Kong, identified a specific protein that acts as an 'exercise sensor' for bones. When activated, it promotes bone growth and reduces fat buildup.

"We need to understand how our bones get stronger when we move or exercise before we can find a way to replicate the benefits of exercise at the molecular level," says Xu Aimin, a biomedical scientist at the University of Hong Kong. "This study is a critical step towards that goal."

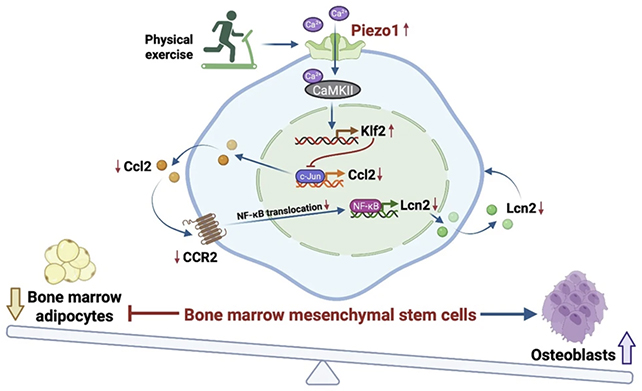

The research focused on bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMMSCs). In their initial form, they can go in two directions: becoming bone-forming cells called osteoblasts or fat cells called adipocytes.

The path BMMSCs take is determined by a variety of factors, including growth signals, hormones, inflammation levels, and – importantly for this study – the physical forces induced by exercise.

It was already known from experiments with lab-grown cells that mechanical forces tip the balance towards bone growth and away from fat, but the researchers wanted to find out why. They studied a protein called Piezo1, shown in earlier studies to produce biological signals in response to pressure and other forces such as mechanical strain and stress.

When Piezo1 was removed from cells in mice, the animals exhibited lower bone density and reduced bone formation. What's more, the number of adipocytes in the mouse bone marrow increased. Further tests showed that mice without Piezo1 didn't get the same bone-strengthening benefits from exercise.

The researchers also identified the exact signaling pathways used by Piezo1, revealing how its absence leads to inflammation and fat growth. Importantly, these changes were reversible if Piezo1 was activated or its downstream effects were restored. If future drugs are to be developed that mimic Piezo1, this knowledge is key.

"We have essentially decoded how the body converts movement into stronger bones," says Aimin. "We have identified the molecular exercise sensor, Piezo1, and the signalling pathways it controls.

"This gives us a clear target for intervention. By activating the Piezo1 pathway, we can mimic the benefits of exercise, effectively tricking the body into thinking it is exercising, even in the absence of movement."

Our bones typically weaken as we get older, and the risk of osteoporosis increases. For many people, including the elderly and the frail, regular exercise is difficult or impossible. A treatment that could mimic some of exercise's biological benefits might help protect these groups from bone loss.

Such a treatment is still a long way off. This study was carried out in mouse models rather than in humans, and aiming at a target like Piezo1 needs to be done very cautiously – it performs many roles throughout the body. Trying to manipulate its effects could cause even more damage.

Nevertheless, this research and studies like it substantially improve our understanding of how osteoporosis develops. With the elderly population continuing to grow, there's a real need to find ways to stay healthier for longer.

Related: Exercise Is Emerging as a Powerful Treatment For Depression

"This offers a promising strategy beyond traditional physical therapy," says mechanobiologist and senior author Eric Honoré, from the Institute of Molecular and Cellular Pharmacology in France.

"In the future, we could potentially provide the biological benefits of exercise through targeted treatments, thereby slowing bone loss in vulnerable groups such as the bedridden patients or those with limited mobility, and substantially reducing their risk of fractures."

The research was published in Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy.