To consolidate memories, our brains replay them during periods of rest as a kind of 'replay mode'. A new mouse study suggests that disruptions to this process could contribute to the memory loss that accompanies Alzheimer's disease.

According to the research team from University College London, these findings could lead the way towards opportunities to diagnose Alzheimer's at an earlier stage and to treat the associated brain damage.

"Alzheimer's disease is caused by the build-up of harmful proteins and plaques in the brain, leading to symptoms such as memory loss and impaired navigation – but it's not well understood exactly how these plaques disrupt normal brain processes," says neuroscientist Sarah Shipley.

"We wanted to understand how the function of brain cells changes as the disease develops, to identify what's driving these symptoms."

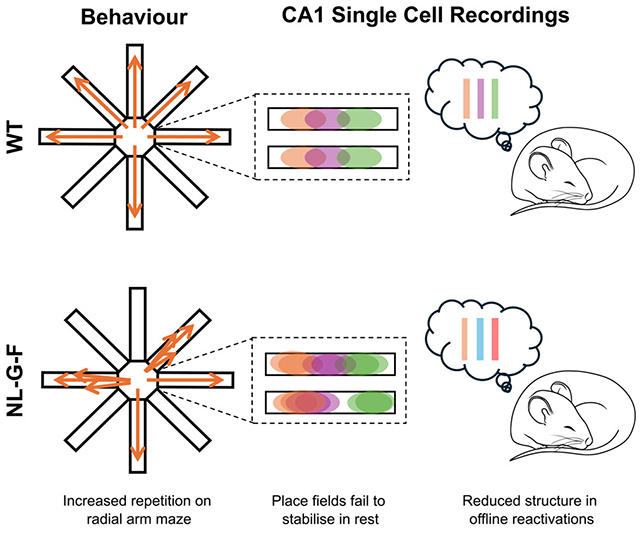

The mice in the study were given an Alzheimer's-like condition, with toxic build-ups of amyloid-beta protein in their brains. When navigating mazes, the test animals showed signs of being unable to lock a spatial map into their memories.

Both during the maze challenges and while the mice were at rest between sessions, Shipley and her colleagues monitored activity in their hippocampi, a region of the brain containing location-memory neurons known as place cells.

For the mice to recall where they've been, these cells must fire in a particular order. As the memories are 'saved' for longer-term storage, that sequence of activation repeats, like a replay.

The frequency of these replays didn't change in mice with amyloid-beta plaques in their brains, but the ordering of the sequences did. It was as if the memories were scenes in a mini-movie, which were chopped up and stored in different places.

This was seen in maze behavior, too, with the affected mice often forgetting which parts of the maze they had already visited, even in the same session. The place cells also became less stable over time, with the cell-to-location mapping becoming messed up.

Although this study used a model of Alzheimer's in mouse brains, there are good reasons to think the same kind of breakdown is happening in humans with the disease – something that could be confirmed through future studies.

"We've uncovered a breakdown in how the brain consolidates memories, visible at the level of individual neurons," says neuroscientist Caswell Barry.

"What's striking is that replay events still occur – but they've lost their normal structure. It's not that the brain stops trying to consolidate memories; the process itself has gone wrong."

Alzheimer's disease is a complex condition with multiple risk factors. There are various potential causes and numerous impacts on the brain, which may be working together or separately.

Part of the difficulty for researchers comes in trying to work out what's driving the progress of Alzheimer's, and what's happening as a consequence of it – and there's that uncertainty around amyloid-beta build-up too.

Related: Bacteria at The Back of Your Eye May Be Linked With Alzheimer's Progress

Studies like this add pieces to the overall jigsaw, letting us see more of the 'big picture' of Alzheimer's – and how all these causes and consequences fit together as brain functionality degrades over time.

Each new discovery means that we might be able to spot signs of the disease earlier – giving more time for treatments and support to be put in place – and develop treatments to target certain parts of Alzheimer's.

In this case, that might be drugs that help to sharpen replay activity in the hippocampus's place cells. However, that won't be possible until more research can specifically identify the processes at play and how they can be safely tweaked.

"We hope our findings could help develop tests to detect Alzheimer's early, before extensive damage has occurred, or lead to new treatments targeting this replay process," says Barry.

The research has been published in Current Biology.