A common bacterium usually found in the respiratory system appears to be linked to cognitive decline and Alzheimer's disease when it's present in the retina.

Chlamydia pneumoniae – often responsible for pneumonia and sinus infections – has previously been spotted in brains affected by Alzheimer's. Now, a new study has detected C. pneumoniae in the vision-generating tissue that lines the back of the eye, at higher levels in people with Alzheimer's.

Led by a team from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in the US, the research provides fresh insight into the biological processes that may worsen Alzheimer's progression – and could inspire new approaches to slowing the disease.

As well as potentially contributing to the cascade of mechanisms that lead to Alzheimer's, the presence of C. pneumoniae in the retina could also one day be used to detect cognitive decline and dementia – though that possibility wasn't directly tested here.

"The eye is a surrogate for the brain, and this study shows that retinal bacterial infection and chronic inflammation can reflect brain pathology and predict disease status, supporting retinal imaging as a noninvasive way to identify people at risk for Alzheimer's," says neuroscientist Maya Koronyo-Hamaoui, from the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

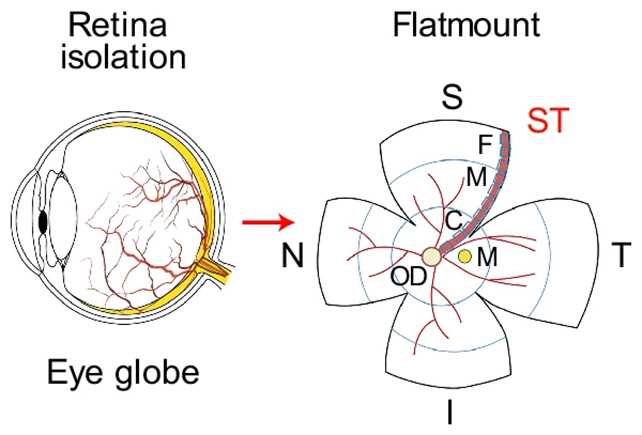

To begin with, the team analyzed eye and brain tissue from 104 people after death. Some had Alzheimer's disease, some had mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and some hadn't reported any cognitive problems.

They found a clear association between the presence of C. pneumoniae in the eye and brain and having a diagnosis of Alzheimer's. Higher levels of the bacterium in tissue were linked to more severe cognitive decline.

People with APOE gene variants linked to Alzheimer's risk also had higher levels of the bacterium in their tissues. However, the differences between people without cognitive impairment and those with MCI were much less clear-cut when it came to C. pneumoniae.

Next, the researchers ran tests using lab-grown neurons and animal models to determine what C. pneumoniae might be doing biologically. These experiments showed that infections with the bacterium led to increased inflammation, greater cognitive decline, and more nerve cell death.

The presence of C. pneumoniae was also associated with increased amounts of amyloid-beta protein in the brain, which is known to clump together in dangerous ways in the brains of people with Alzheimer's.

"Seeing Chlamydia pneumoniae consistently across human tissues, cell cultures, and animal models allowed us to identify a previously unrecognized link between bacterial infection, inflammation, and neurodegeneration," says Koronyo-Hamaoui.

There are still unanswered questions, and the findings are only a strong suggestion that C. pneumoniae could contribute to (and be a sign of) Alzheimer's disease – not conclusive proof.

However, if infection by the bacterium is indeed leading to inflammation that extends to the brain and accelerates neurodegenerative processes, then we may have a new target for future treatments.

The researchers describe C. pneumoniae as a potential amplifier rather than a primary trigger, which aligns with growing evidence of just how complex Alzheimer's is. It's likely there are multiple contributing factors that may differ between people.

What's more, the team identified a specific inflammation pathway that C. pneumoniae targets, possibly worsening the damage already being done by Alzheimer's. Further studies will be required to confirm this mechanism, but the signs are there.

Related: A Common Sleeping Pill May Reduce Buildup of Alzheimer's Proteins, Study Reveals

Scientists continue to identify multiple ways the eyes and the brain are linked. In this case, the findings could prove valuable to society's ongoing efforts to combat Alzheimer's and other forms of dementia.

"This discovery raises the possibility of targeting the infection-inflammation axis to treat Alzheimer's," says biomedical scientist Timothy Crother, from the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.