Our episodic memory – the ability to recall past events and experiences – is known to decline as we age. Exactly how and why has remained something of a mystery, and a recent study goes some way towards solving it.

Researchers led by a team from the University of Oslo in Norway wanted to see whether this memory loss affects everyone equally, or if it might be driven by individual risk factors, such as the APOE ε4 gene linked to Alzheimer's disease.

The scale of their analysis is impressive. The scientists combined data from 3,737 cognitively healthy participants, tracked over several years, including 10,343 MRI scans and 13,460 memory assessments, from multiple long-running studies.

Related: We May Now Know Why Alzheimer's Erases Memories of Our Loved Ones

"By integrating data across dozens of research cohorts, we now have the most detailed picture yet of how structural changes in the brain unfold with age and how they relate to memory," says neurologist Alvaro Pascual-Leone, from the Marcus Institute for Aging Research at Harvard Medical School.

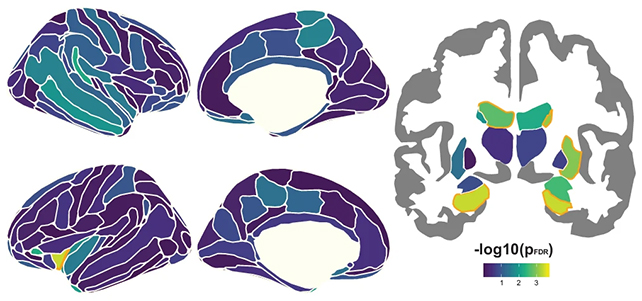

The results showed a complex picture. While the hippocampus – a brain region central to memory and learning – was most significant here, as expected, memory decline was not linked to changes in a single area alone.

Reductions in brain tissue volume were linked to poorer episodic memory, which was not surprising, but the association was far from uniform. It became much clearer with age, especially in those older than 60, and was strongest in participants whose brains were shrinking faster than average.

Among those carrying the APOE ε4 gene, the researchers observed a more rapid loss of brain tissue volume and decline in memory compared to other participants, but the general trajectory was the same.

"Cognitive decline and memory loss are not simply the consequence of aging, but manifestations of individual predispositions and age-related processes enabling neurodegenerative processes and diseases," says Alvaro Pascual-Leone.

The findings raise plenty of questions and offer some answers, but overall they suggest that memory loss isn't necessarily a separate process from aging – and that the older we get, the more brain changes matter for memory.

There are also implications for treatments to slow or prevent memory loss: They'll need to target multiple brain areas, and may be most effective if started as early as possible. The good news is that the same therapies are likely to work for those with or without the APOE ε4 gene, as the underlying mechanisms appear to be shared.

Related: Scientists Found an Early Signal of Dementia Hidden in Terry Pratchett's Novels

It's becoming clear that a variety of different factors can influence memory loss in later life, as part of a broader set of cognitive capabilities. The more we learn about those factors, the better our chances of managing them.

"These results suggest that memory decline in aging is not just about one region or one gene – it reflects a broad biological vulnerability in brain structure that accumulates over decades," says Alvaro Pascual-Leone.

"Understanding this can help researchers identify individuals at risk early, and develop more precise and personalized interventions that support cognitive health across the lifespan and prevent cognitive disability."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.