Some brain cells can resist the toxic processes associated with Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia. Scientists have now identified the "cellular hazmat team" that keeps neurons healthy.

Neurodegenerative diseases like dementia are characterized by proteins that aggregate in the brain and kill neurons. Tau proteins are one of the main culprits, but they're not always villains.

In their functional state, they help to stabilize brain structures and facilitate nutrient transport. But misfolded tau proteins clump together, and a higher degree of clumping indicates more advanced neurodegenerative diseases.

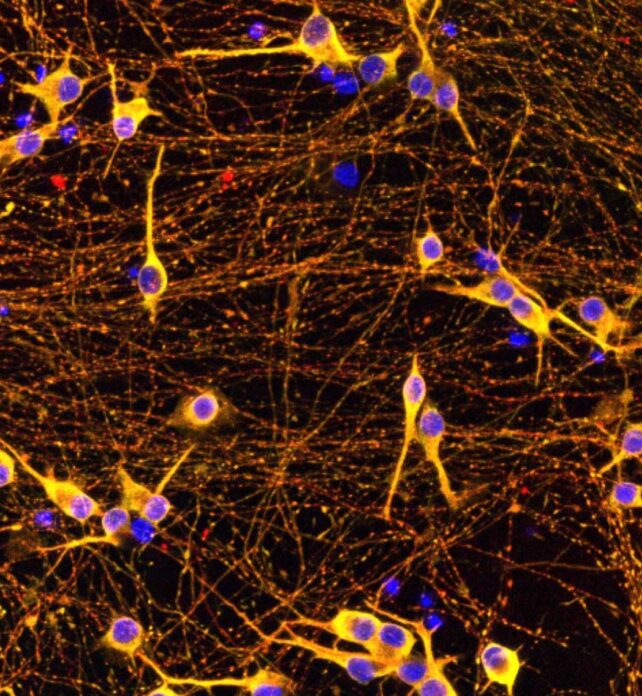

In a recent study, researchers from UCLA Health and UC San Francisco used CRISPR-based screening to explore tau accumulation in lab-grown neurons derived from human stem cells. But there's a uniquely relevant twist.

"What makes this study particularly valuable is that we used human neurons carrying an actual disease-causing mutation," says Avi Samelson, assistant professor of neurology and biological chemistry at UCLA Health and the study's first author.

"These cells naturally have differences in tau processing, giving us confidence that the mechanisms we identified are relevant to human disease."

The disease-causing mutation, MAPT V337M, leads to increased aggregation of tau proteins that adopt a harmful shape known as the "Alzheimer fold".

In the past, researchers have combed the human genome to uncover the factors that modify disease risk, but not their underlying molecular mechanisms. Others have described differences between neurons, but lacked the experimental basis necessary to pinpoint causality.

"It's the first time we've been able to screen human neurons for genes that determine their resilience to tau," says Martin Kampmann, professor of biochemistry and biophysics at UC San Francisco and the study's senior author.

Using CRISPR, the researchers systematically screened "nearly every gene in the human genome".

They knocked down or inactivated 20,000 individual genes in the in vitro human neurons to determine how each gene affects toxic tau protein clumping. Overall, more than 1,000 genes were implicated in the buildup of brain-harming clumps.

Additional screening identified a key player, a protein complex called CRL5SOCS4, that helps brain cells resist toxic tau accumulation. CRL5SOCS4 does so by attaching a molecular tag to tau proteins, which marks them for destruction by proteasomes, the "garbage disposal" units of cells.

To ascertain if in vitro findings match observations in actual cases, the researchers consulted the Seattle Alzheimer's Disease Brain Atlas, a compilation of data derived from the brain tissues of deceased patients with Alzheimer's. Accordingly, the researchers found that the brain cells with higher CRL5SOCS4 expression showed greater survivability.

Toxic tau components can also result from mitochondrial dysfunction. As many may know from science memes, mitochondria are the powerhouses of the cell. And when the researchers knocked down genes that affect mitochondrial function, they triggered the generation of tau protein fragments.

These fragments are small but similar to a highly accurate biomarker present in the blood and spinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer's. Cells appear to produce this tau fragment in response to oxidative stress, a form of stress that occurs during energy production and increases with aging and neurodegeneration.

As a result, dysfunction in mitochondrial genes can make tau more "sticky" and likelier to clump.

Overall, this study highlights how genetic screening methods can reveal unknown disease mechanisms. For example, the researchers found some very interesting new pathways that control tau levels, though it is uncertain how they work.

Additionally, clinicians must find ways to translate these findings into actionable treatments. The researchers suggest two therapeutic options. The first is to enhance CRL5SOCS4 activity, leading to more effective removal of tau proteins before they clump.

One way to achieve this is to find molecules that strengthen the interaction between CRL5SOCS4 and tau. Treatments may also aim to protect proteasomes from oxidative stress, because a stressed proteasome cannot properly process tau proteins.

Related: Daily Caffeine Could Reduce Your Risk of Developing Dementia, Study Shows

As with other diseases, human biology has perhaps already achieved the most effective treatments through evolutionary trial and error.

"Maybe a future therapy could enhance the body's natural mechanism for avoiding neurodegeneration," says Kampmann.

This research is published in the journal Cell.