Deep inside the Greenland ice sheet, radar images have revealed strange, plume-like structures distorting the layering deposited over eons.

Now, more than a decade after their discovery, scientists think they have figured out what causes these structures, and it's a real hum-dinger. According to modeling, the plumes are a striking match for convection: the roiling upward transport of heat more commonly linked to the fiery, molten rock churning beneath Earth's crust.

"Finding that thermal convection can happen within an ice sheet goes slightly against our intuition and expectations. Ice is at least a million times softer than the Earth's mantle, though, so the physics just work out," says glaciologist Robert Law of the University of Bergen in Norway.

"It's like an exciting freak of nature."

The Greenland ice sheet, which covers 80 percent of the island, is one of our planet's biggest reservoirs of frozen water, and is forecast to play a major role in rising sea levels as it melts into the ocean. Understanding the physics inside it is vital for predicting how the ice sheet will change over time.

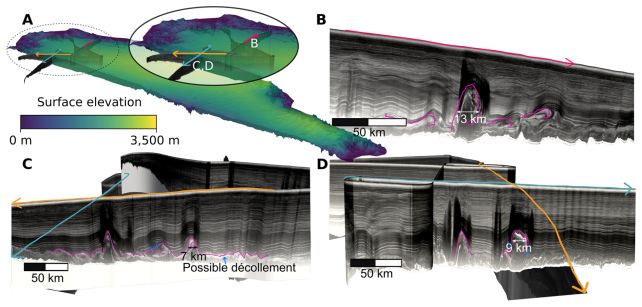

This is why scientists use ice-penetrating radar. Radio waves pass through the ice and reflect back differently as they encounter internal layers – snow that fell long ago and was compacted into ice as more snow piled on top. Each of these layers has its own characteristics – slightly different acidity levels, for example, and variations in dust, ash, and chemical content.

In a 2014 paper, scientists described strange structures these radar images had revealed deep inside the ice in northern Greenland. These large, upward-buckling features were unrelated to the topography of the bedrock below, presenting a puzzle researchers have been trying to solve ever since.

Previous efforts suggested that mechanisms such as glacial meltwater freezing onto the underside of the ice sheet, or migrating slippery spots, may be responsible for the structures. One idea that had not been tested, however, was that thermal convection may take place within ice sheets.

To test the idea, Law and his colleagues turned to computer modeling. They built a simplified digital slice of the Greenland ice sheet and asked a simple question: If the base of the ice is warmed from below, could convection form structures that match what radar sees?

They used a geodynamics modeling package normally used to simulate convection in Earth's mantle to model a slab of ice 2.5 kilometers (1.6 miles) thick. They tweaked variables such as snowfall rate, ice thickness, how soft the ice is, and how fast the ice moves on the surface.

Under the right conditions, the model began producing plume-like upwellings – rising columns of ice that folded the overlying layers into shapes strikingly similar to those seen in radar images.

In the model, plumes only formed when the ice near the base was warmer and significantly softer than standard assumptions allow, suggesting that if convection is responsible, the real ice at the base of northern Greenland's ice sheet may also be softer than previously thought.

Meanwhile, the heat required to produce these convection upwellings in the model was consistent with the heat continuously flowing from Earth, generated by the radioactive decay of elements within the crust and by residual heat from Earth's formation as it gradually cools over billions of years.

This effect is tiny, but over time, and under a giant slab of insulating material, it could build up enough to warm and soften the ice above it.

"We typically think of ice as a solid material, so the discovery that parts of the Greenland ice sheet actually undergo thermal convection, resembling a boiling pot of pasta, is as wild as it is fascinating," says climatologist Andreas Born of the University of Bergen.

Related: World's Deepest Gas Hydrate Discovered Teeming With Life Off Greenland

Now, that doesn't mean the ice is slushy. It's still solid ice, flowing only on timescales of thousands of years. It also doesn't necessarily mean that it will melt faster. Further investigation into the physics of ice, and the effects of convection on the evolution of the ice sheet, is required to determine what this means for the future.

"Greenland and its nature is truly special. The ice sheet there is over one thousand years old, and it's the only ice sheet on Earth to have a culture and permanent population at its margins," Law says.

"The more we learn about the hidden processes inside the ice, the better prepared we'll be for the changes coming to coastlines around the world."

The research has been published in The Cryosphere.