A few blobs of lab-grown brain tissue have demonstrated a striking proof of concept: living neural circuits can be nudged toward solving a classic control problem through carefully structured feedback.

In a closed-loop system that delivered electrical feedback based on performance, cortical organoids could steadily improve their control of a classic engineering benchmark: balancing an unstable virtual pole.

The improvement is far from a functioning hybrid biocomputer. But as a proof of concept, it shows that neural tissue in a dish can be adaptively tuned through structured feedback – a result that could help researchers probe how neurological disease alters the brain's capacity for plasticity.

"We're trying to understand the fundamentals of how neurons can be adaptively tuned to solve problems," says Ash Robbins, robotics and artificial intelligence researcher at the University of California (UC) Santa Cruz.

"If we can figure out what drives that in a dish, it gives us new ways to study how neurological disease can affect the brain's ability to learn."

The cartpole problem is conceptually simple. Imagine balancing a long object, such as a ruler or a pen, upright on your open hand. Unless it's perfectly aligned, it will start to tip. To keep it standing, you have to constantly adjust your hand's position as the object teeters and wobbles.

In the cartpole version, a virtual cart can move left or right to keep a hinged pole balanced vertically. The rules are straightforward, and there's a clear failure point when the pole tips too far. But small errors compound quickly, making it a classic example of an unstable control problem.

Cartpole is often used in reinforcement learning research: it's easy to simulate and fast to run, but unlike pattern recognition tasks, it requires constant, fine-grained adjustments rather than a single correct response.

For Robbins and his colleagues, the cartpole represented a new and clean way to test the capabilities of brain organoids.

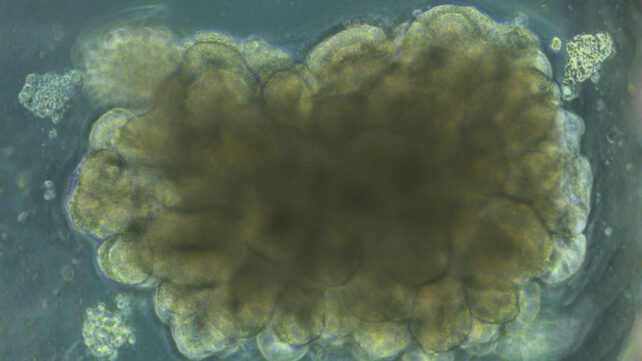

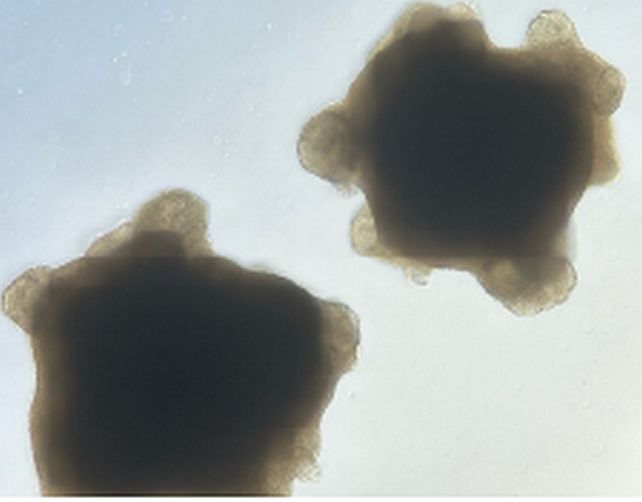

The organoids were not grown from human tissue, but mouse stem cells cultivated to grow into small clusters of cortical tissue capable of neural signaling. These organoids were not complex enough for anything approaching thought or sentience, but they could send and receive electrical signals, and their internal connections could change in response to external stimulation.

The experiment revolved around a virtual cartpole. Different electrical stimulation patterns signaled the direction and degree of the pole's tilt. The organoids' responses were then interpreted as left or right forces to move the cart and counteract the wobble.

To be clear, the organoids had no understanding of the task. The researchers were testing whether the tissue's neuronal connections could be tuned through feedback – that is, whether bursts of electrical stimulation could produce changes that nudged the network toward better control.

Each attempt to balance the pole (known as an episode) lasted until it tipped past a preset angle. Performance was tracked over rolling five-episode windows. The organoids were assigned to one of three conditions: no feedback, random feedback delivered to selected neurons, or adaptive feedback based on past performance.

The adaptive condition is the crucial one. If performance over five episodes fell relative to the recent 20-episode average, the system delivered a brief burst of high-frequency stimulation. An algorithm adjusted which neurons received those bursts based on whether similar stimulation patterns had previously been followed by improved control.

"You could think of it like an artificial coach that says, 'you're doing it wrong, tweak it a little bit in this way,'" Robbins explains. "We're learning how to best give it these coaching signals."

To decide whether the organoids were genuinely improving rather than just getting lucky, the researchers set a benchmark based on how well a completely random controller could perform. If the organoid's strongest performances during a session exceeded what randomness alone could plausibly produce, that session was counted as proficient.

The performance proficiency rates achieved for each of the conditions were striking. Organoids given no feedback reached the benchmark for strong performance just 2.3 percent of the time, and those that received random feedback performed well 4.4 percent of the time. Under continuous adaptive feedback, however, the organoids crossed the proficiency threshold in 46 percent of the cycles.

"When we can actively choose training stimuli, we can actually shape the network to solve the problem," Robbins says. "What we showed is short-term learning, in that we can take an organoid in one state and shift it into another one that we're aiming at, and we can do that consistently."

Related: Scientists Grew Stem Cell 'Mini Brains' And Then The Brains Sort of Developed Eyes

However, "short-term" is correct. If left inactive for a period of time – just 45 minutes – the organoids 'forgot' their training, dropping back to a baseline performance. Future work could investigate how to improve the organoid's memory, perhaps by increasing its complexity.

"Ash's software could build a larger community around adaptive organoid computation. But we want to make it clear that our goal is to advance brain research and the treatment of neurological diseases, not to replace robotic controllers and other kinds of computers with lab-grown animal brain tissues," says bioinformatician David Haussler of UC Santa Cruz.

"The latter might be considered cool, but would bring up serious ethical issues, especially if human brain organoids were used."

The research has been published in Cell Reports.