In 1879, astronomer Benjamin Gould identified what looked to be a ring in the sky, measuring about 3,000 light-years across, made of dust and gas and young stars - interconnected stellar nurseries. Now, a new discovery has shattered our understanding of this structure, which has been known for 150 years as Gould's Belt.

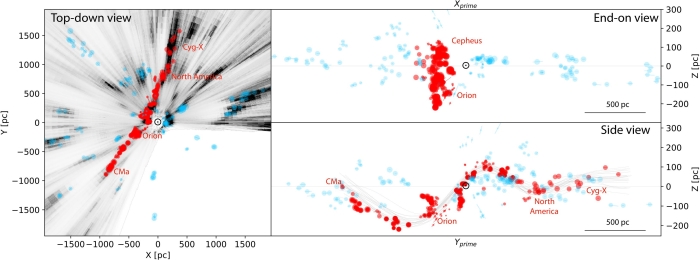

According to data collected by the Gaia mapping survey of the Milky Way galaxy, Gould's Belt is just part of a much larger structure - a colossal, serpentine wave of gas and dust 9,000 light-years long, 400 light-years wide, and extending 500 light-years above and below the galactic plane.

This wave - newly named the Radcliffe Wave, after Harvard University's Radcliffe Institute of Advanced Study, where the research was conducted - includes many of the stellar nurseries found in Gould's Belt, and others besides.

It's the largest gaseous structure identified in the Milky Way (although not the largest structure in the galaxy; the Fermi gamma-ray bubbles, for example, span 50,000 light-years).

"No astronomer expected that we live next to a giant, wave-like collection of gas - or that it forms the local arm of the Milky Way," said astronomer Alyssa Goodman of the Smithsonian Institution, and co-director of the Science Program at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

"We were completely shocked when we first realised how long and straight the Radcliffe Wave is, looking down on it from above in 3D - but how sinusoidal it is when viewed from Earth. The Wave's very existence is forcing us to rethink our understanding of the Milky Way's 3D structure."

The Gaia satellite was launched in 2013, and has been collecting data ever since to produce the most accurate 3D map yet of our home galaxy, the Milky Way. This is what the researchers were studying to try to get a better understanding of the structure of Gould's Belt - to determine if the clouds do, in fact, form a ring in three dimensions.

They also used recently developed techniques based on the colour of stars to map the 3D distribution of dust around them, and to accurately measure the distances to stellar nurseries - regions where clumps of dust and gas collapse under their own gravity to form new stars.

Yet, as they looked closer at the data, they realised they were looking at a structure of these interconnected regions, but also a structure that was much bigger than Gould's Belt itself.

"Instead, what we've observed is the largest coherent gas structure we know of in the galaxy, organised not in a ring but in a massive, undulating filament," said physicist and astronomer João Alves of the University of Vienna in Austria.

"The Sun lies only 500 light-years from the Wave at its closest point. It's been right in front of our eyes all the time, but we couldn't see it until now."

(Alve et al., Nature, 2019)

(Alve et al., Nature, 2019)

If you look at it from the top down (obviously we can't physically do this, but we can simulate the perspective with a computer-generated map), the Radcliffe Wave is more or less a straight line. Come back down to the galactic plane and look at it side-on, however, and it has an impressive sinuous wiggle.

It's a peculiar shape, and it's not entirely clear how it came about. "It could be like a ripple in a pond, as if something extraordinarily massive landed in our galaxy," Alves said.

We know such a thing is possible - Gaia data have also helped previously identify giant ripples across the Milky Way's disc, thought to have been created by the collision with a dwarf galaxy less than a billion years ago. But the team's paper offers no speculation about the event that could have created the Radcliffe Wave, although those investigations could form the basis of a future study.

What they do know is that it does, on occasion, (harmlessly) interact with the Sun.

"[The Sun] passed by a festival of supernovae as it crossed Orion 13 million years ago," Alves said, "and in another 13 million years it will cross the structure again, sort of like we are 'surfing the wave'."

The research has been published in Nature.