A dedicated scan for signs of radio-transmitting technology in interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS has come back with absolute cometary radio silence.

The Breakthrough Listen project used one of the world's biggest, most sensitive radio telescopes, the 100-meter Green Bank Telescope, to listen for several hours to the comet roughly a day before it reached perigee on 19 December 2025.

The team searched for artificial technosignatures across a wide range of radio frequencies, and while many signals were heard, not a single one turned out to be from the comet.

That's not a surprise – there's absolutely nothing about 3I/ATLAS that indicates anything other than "comet" – but, well, the Universe handed humanity this opportunity on a platter. We'd have been silly NOT to look.

Related: 4 Powerful Telescopes Agree: Interstellar Comet 3I/ATLAS Really Is Bizarre

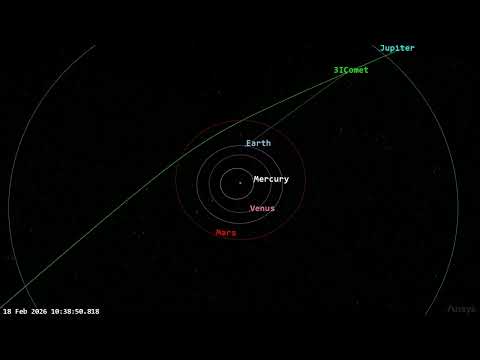

3I/ATLAS was discovered on 1 July 2025, and calculations of its trajectory revealed it had come from outside the Solar System. In late October, the comet made its closest approach to the Sun, or perihelion; its closest approach to Earth, or perigee, came nearly two months later, as it made its way back out towards interstellar space.

Perigee brought it to a distance of around 270 million kilometers (168 million miles). That's nearly twice Earth's 150 million-kilometer distance from the Sun, but still close enough to take some detailed observations.

On December 18, a team led by astronomer Ben Jacobson-Bell of the University of California, Berkeley deployed the Green Bank Telescope to listen to the comet over a period of five hours.

If the comet sent a radio transmission of the kind the search was designed to detect during that window, Green Bank would have picked it up.

To make sure that the signals picked up by the telescope were coming from 3I/ATLAS, the observations alternated between pointing at the comet and pointing at other patches of the sky in an expanding fractal pattern known as an ABACAD arrangement, switching every five minutes.

Once the signals that appeared in other patches of the sky had been removed, the researchers were left with nine candidate radio signals. Closer observations revealed that these nine signals were from technology; they just happened to be radio-frequency interference from human technology on and around Earth.

Sad trombone.

To be clear, that doesn't conclusively rule out the possibility that 3I/ATLAS may harbor alien technology. It's not unheard of for humanity's own probes to fall radio silent for long stretches at a time. In fact, by the time the Voyager probes travel for as long as 3I/ATLAS has, up to billions of years if they survive that long, their power supplies will have long since died.

Everything else we know about 3I/ATLAS, however, is entirely consistent with a comet.

"This object is a comet," NASA associate administrator Amit Kshatriya said in November. "It looks and behaves like a comet, and all evidence points to it being a comet. But this one came from outside the Solar System, which makes it fascinating, exciting, and scientifically very important."

So why look if we know we're not likely to find anything? Because looking is what science is all about. Even finding nothing tells us something. In this case, the 'nothing' tells us at the very least that 3I/ATLAS isn't an alien beacon sent to broadcast a message in radio frequencies across the Solar System.

We already knew that, mostly; now we know it even harder, which is useful for future research.

Plus, although scientists were reasonably certain that 3I/ATLAS was not an alien probe, can you imagine if it had been, and we missed the detection just because we were too 'reasonably certain' to take a straightforward measurement?

Observations like these are useful in other ways, too.

"These discussions give non-scientists an indication of the sorts of amazing observations being made, the fun that scientists have thinking about them, and the possibilities that are out there," physicist Paul Ginsparg of Cornell University, and the founder of arXiv, told ScienceAlert in 2019.

"Wild speculation can sometimes inform the next generation of instrumentation, which can then either confirm or refute the wild hypothesis, or see something else entirely and unexpected. And that too is what makes science fun."

The results of the campaign are available on preprint server arXiv.

Top image credit: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/Shadow the Scientist/Image Processing: J. Miller & M. Rodriguez (International Gemini Observatory/NSF NOIRLab), T.A. Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage/NSF NOIRLab), M. Zamani (NSF NOIRLab)