The Sun has been up to some pretty intense shenanigans lately, but a recent eruption on the far side looks to be absolute science gold.

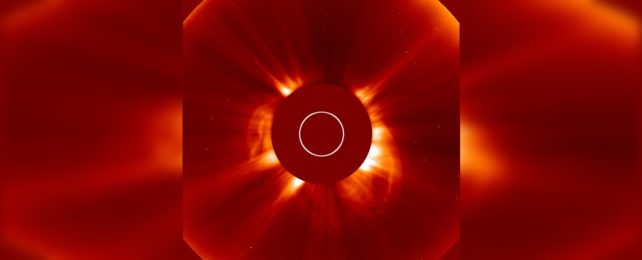

On the evening of September 5 GMT, an enormous coronal mass ejection (CME) was recorded exploding on the far side of the Sun, sending a radiation storm out across the Solar System. It was a type known as a halo CME, in which an expanding halo of hot gas can be seen spewing out around the entire Sun.

Sometimes this means that the CME is headed straight for Earth. However, this eruption was on the far side, so it's heading away, and we won't see any of the usual effects of a solar storm here on our home planet.

But Venus was right in the path of the oncoming storm – and with it, Solar Orbiter, a space probe jointly run by the European Space Agency and NASA that is currently near Venus after a September 4 gravity assist on its mission to take closeup observations of our home star.

This has given us the rare opportunity to observe and measure a gigantic, farside CME, something that is usually rather difficult for us to do.

"This is no run-of-the-mill event. Many science papers will be studying this for years to come," solar physicist George Ho of the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory told Spaceweather.

"I can safely say the Sept. 5th event is one of the largest (if not THE largest) Solar Energetic Particle (SEP) storms that we have seen so far since Solar Orbiter launched in 2020."

It's unclear exactly where the Sun erupted from, but it seems likely that the culprit is a sunspot region called AR 3088, which rotated away behind the disk of the Sun at the end of August.

SOLAR DISCO: AR3088 is stayin' alive - blasting out light and matter on its journey around the Sun. It's still providing an amazing show even out of our view. Here is a look at the region over 2.5 days ending with its big M2 blast directed away from us. SDO 171/193/131 🧐🙀🤩😆👋 pic.twitter.com/lXGiUQC3Os

— Dr. C. Alex Young (@TheSunToday) August 31, 2022

As it did so, it left a parting shot – a huge M2-class flare, directed away from Earth.

Helioseismology – the study of internal oscillations of the Sun, based on surface vibrations – can be used to detect sunspots on the far side of our home star.

That's because accumulations of magnetic fields, such as sunspots, can affect the speed of sound waves bouncing around inside the Sun.

Helioseismic measurements from NASA suggest that AR 3088 may have grown after it departed our side of the Sun.

It's relatively quiet on the Earth-facing side of the Sun compared to the recent action with AR3088. A large eruption recently occurred on the far side. A likely candidate, ole' AR3088. Helioseismology shows a big region. Probably our old friend. 🧐🌞🙀👏 pic.twitter.com/fjp97I4Sp2

— Dr. C. Alex Young (@TheSunToday) September 6, 2022

There are many spacecraft that might not survive such an intense buffeting from the Sun. But Solar Orbiter, as the name suggests, was built to withstand quite a solar pummeling.

And it's equipped with instrumentation to measure solar phenomena, including the Sun's violent eruptions.

In fact, Solar Orbiter had been in the path of an earlier CME that erupted on August 30 GMT, just prior to the gravity assist maneuver.

Its instruments recorded, in both events, a significant uptick in solar energetic particles. This is information that can help scientists categorize these events, and better understand the behavior of the Sun, and its impact on the space environment.

The high-energy particle intensities remain high; and looks like an interplanetary shock just passed through @ESASolarOrbiter early today. CME should be following soon. pic.twitter.com/yF5njp5QRu

— George Ho (@mrgho06) September 6, 2022

AR 3088 is still on the far side of the Sun, and, if it's going to re-emerge, won't do so for some days. So it's entirely possible that, by the time it gets back around to us, it will be smaller and quieter.

Currently, all is quiet in Earth-directed Sun-land, with no solar storms on the horizon.

There are a few sunspot regions visible, but they all seem to be fairly subdued for the time being, with only milder CMEs erupting on the solar near side.

However, the Sun is getting into the peak of its 11-year activity cycle, so we should see more powerful eruptions occurring in the not-too-distant future.

If you want to stay on top of solar weather forecasts, and what they mean for Earth, you can check in on you can follow the NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center, the British Met Office, the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, and SpaceWeatherLive at their respective websites.