We've known about the iconic Ring Nebula for nearly 250 years, but it's only now that astronomers have found a giant mystery right at its core.

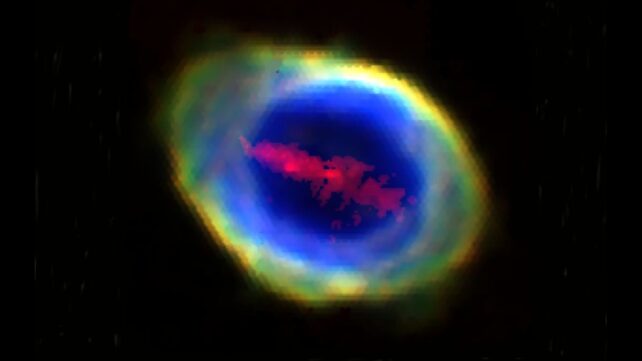

There, stretching across the heart of the cloud of cosmic dust and gas, lies a giant, oddly linear, bar-shaped cloud of glowing, ionized iron atoms. A structure of this nature has never been found in a nebula before, and it has a whole host of unusual properties that make it challenging to explain.

It's the hope of a team of astronomers led by Roger Wesson of Cardiff University in the UK that further observations of other nebulae will pick out more of these strange iron clouds, enough to piece together where in the heck it came from.

Related: Rainbow Discovered Around a Nearby Dead Star Puzzles Scientists

The Ring Nebula is a planetary nebula 2,570 light-years away in the constellation of Lyra, discovered by the French astronomer Charles Messier in 1779. These glowing blobs in the sky have nothing to do with planets, but are the beautiful guts of dying Sun-like stars.

At the ends of their lives, these stars gently sneeze off their outer layers, while the core of the star collapses into a white dwarf.

Because this process is so muted compared to the violent supernova deaths of massive stars, the ejected material can often form lovely, neat, spherical structures in the sky.

There are thousands of known and possible planetary nebulae in the Milky Way, so astronomers are pretty knowledgeable about what to expect. In addition, the Ring Nebula is one of the most famous and most well-studied, so it wasn't expected to yield any wacky surprises.

Yet, here we are.

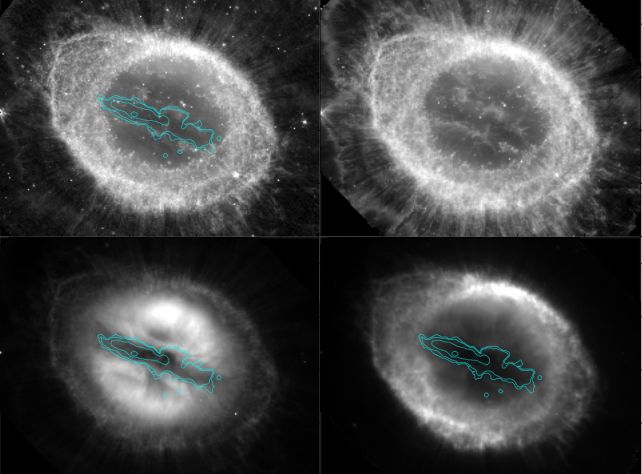

The observations were made using the Large Integral Field Unit (LIFU) mode of the new WHT Enhanced Area Velocity Explorer (WEAVE) instrument on the 4.2-metre William Herschel Telescope. This mode allows WEAVE to capture a large field in a single shot, providing a comprehensive spectroscopic observation of an entire object.

"Even though the Ring Nebula has been studied using many different telescopes and instruments, WEAVE has allowed us to observe it in a new way, providing so much more detail than before," says astronomer Roger Wesson of Cardiff University in the UK.

"When we processed the data and scrolled through the images, one thing popped out as clear as anything – this previously unknown 'bar' of ionized iron atoms, in the middle of the familiar and iconic ring."

Previous spectroscopic observations of the Ring Nebula had only been made using slit spectroscopy, which is exactly what it sounds like: viewing a single, thin slice of the nebula. This explains why the iron bar went unnoticed for so long; slit observations would have found it only if the slit was aligned exactly along the bar's orientation.

Its evasiveness is not the only strange thing about the iron bar. At first glance, it looks like a jet of material erupting from a star – but it's not. Closer examination revealed that the white dwarf responsible for the Ring Nebula is offset from the center of the bar, so it's not likely to be the source of the iron atoms.

The motion of the bar is wrong for a jet, too. Emission lines from the length of the bar suggest the entire structure is moving away from us; one end isn't getting closer as the other recedes, as you would expect from two jets pouring out of a star in opposite directions.

The mystery deepens with the bar's composition; some 14 percent of Earth's mass worth entirely of bare, glowing iron atoms (more than the mass of Mars) hanging out in the middle of a nebula, with very few clues about how it got there.

Iron in nebulae is usually locked away in dust, not hanging around naked and ionized. And there's no other emission in the nebula that has the same shape as the bar of iron.

One possibility is that a large amount of dust was somehow destroyed, releasing the iron. That lines up with JWST observations, which reveal dust on either side of the iron bar, but not overlapping it.

However, there's no evidence of the conditions required to release iron from dust in the nebula. To ionize the iron, you'd need either very powerful shocks or very high temperatures. The serene center of the Ring Nebula shows no evidence of either.

The press release on the bar proposes a torn-apart planet as an explanation… but the debris of a torn-apart planet doesn't form a neat, straight bar, and would also show a clear velocity pattern (orbital or expansion) that doesn't match the observations. Plus, it would have other elements mixed in, such as magnesium and silicon, which would have shown up in the observations.

We also need to consider that we can't see the full 3D shape of the iron cloud; it could extend farther beyond our line-of-sight, like a plank of wood being viewed edge-on.

The whole thing is just a big, squishy question mark with no easy answers. Which means looking for more examples and hoping they pony up some clues.

"It would be very surprising if the iron bar in the Ring is unique," Wesson says. "So hopefully, as we observe and analyse more nebulae created in the same way, we will discover more examples of this phenomenon, which will help us to understand where the iron comes from."

The research has been published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.