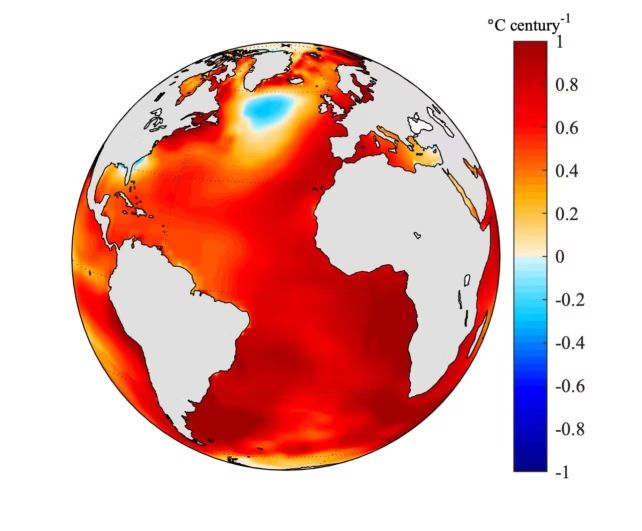

Over the last decade, Earth's oceans have been warming at unprecedented rates, yet one mysterious blob of water, just south of Greenland, has defied this trend. It has stubbornly remained colder than its surrounding waters for over a century now.

"People have been asking why this cold spot exists," says University of California Riverside climate scientist Wei Liu.

To find out, Liu and oceanographer Kai-Yuan Li analyzed a century's worth of temperature and salinity data. They found this mysterious cool patch wasn't limited to the ocean surface, but extended 3,000 meters (around 9,840 feet) deep. And only one scenario they explored could explain both sets of data.

It's the same scenario researchers have been warning the world about for years now: one of Earth's major ocean circulation systems, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), is slowing down.

Related: Giant 'Blobs' in The Pacific Ocean Finally Have Their Origins Revealed

"If you look at the observations and compare them with all the simulations, only the weakened-AMOC scenario reproduces the cooling in this one region," explains Li.

If the AMOC stalls, it will disrupt monsoon seasons in the tropics, and North America and Europe will experience even harsher winters. The knock-on effects will severely impact entire ecosystems and global food security.

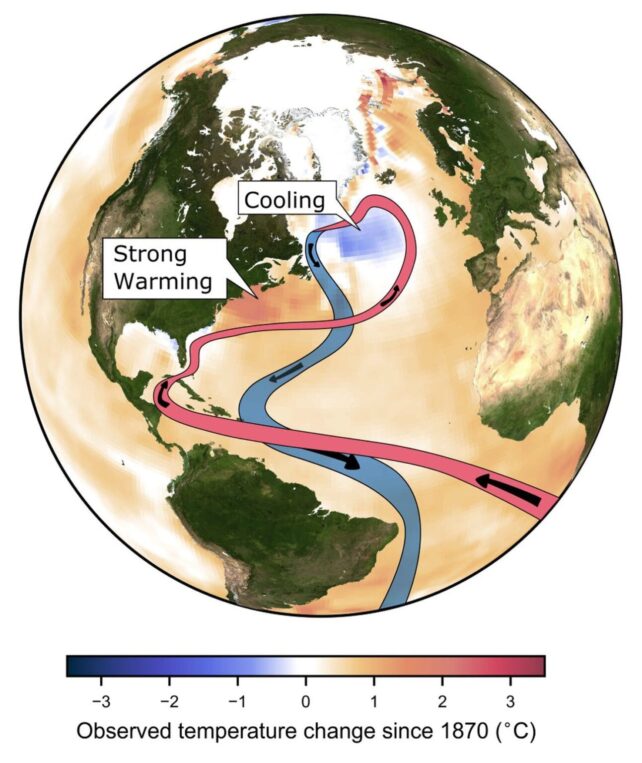

The AMOC is a large heat- and salt-driven system of ocean currents that sweeps warm salty water northward. This water cools on its wending journey north, which makes it denser. As the cooler water sinks, water from other oceans is pulled in to fill the surface, driving the cooler water back down south again.

With increasing contributions of freshwater from climate change-driven glacier melt, concentrations of salt in the sea water drop, and the water becomes less dense, disrupting the sinking-with-cooling process and weakening the entire physical cycle.

That's exactly what the sea surface salinity records showed. Li and Liu found the odd cold spot in the north, near the melting glaciers, had decreasing levels of salinity. Near the equator, however, salinity had increased as the weaker currents failed to stir things up as forcefully.

All up, the researchers calculated AMOC has slowed from -1.01 to -2.97 million cubic meters of water per second between 1900 to 2005.

"This work shows the AMOC has been weakening for more than a century, and that trend is likely to continue if greenhouse gases keep rising," Li concludes.

This research was published in Communications Earth & Environment.