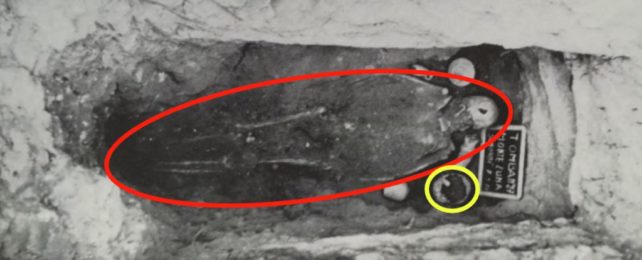

More than 2,000 years ago, a young woman on the Italian island of Sardinia died for unknown reasons. Her body was buried face down in a tomb at the Monte Luna necropolis, the front of her skull pierced by something sharp.

The grave, which dates to about the second or third century BCE, was uncovered and photographed in 1980, but archaeologists are still scratching their heads over the remains and the curious way in which they were buried.

Though the wound was inflicted around the time of her death, it's not considered to be responsible for ending her life, leaving researchers with something of a mystery.

Not only does the front of the woman's skull have a puncture left by a quadrangular-shaped implement of some kind, the back of her skull shows signs of blunt force trauma. Her clavicle also appears have once been fractured, possibly in childhood.

Researchers at the University of Cagliari in Sardinia and James Cook University in Australia have now teamed up to try and explain the mix of injuries.

It's possible, they say, that the young woman, somewhere between the ages of 18 and 22, might have once had epilepsy.

A series of seizures would explain why her skeleton had suffered so many apparent blows and falls in its lifetime.

Strange as it seems, the condition might also explain why her skull was pierced and her body laid face down in her grave.

At this time in human history, epilepsy was considered by many cultures, including the Greeks and Romans, to be the result of fumes wafting from decaying organic materials in what was once termed miasma.

Such fumes, often associated with filth and impurity, led many to assume epilepsy was contagious. One of the most famous Roman scholars, Pliny the Elder, advised the public in the first century CE "to thrust an iron nail into the spot where a person's head lay at the moment he was seized with a fit of epilepsy" to prevent the spread of any contagion to unwitting members of the community.

Perhaps locals living on Sardinia had heard similar advice centuries before, and used the technique after death to ensure the woman's disease didn't spread.

"The blunt force trauma after an epileptic seizure may have been the cause of death and the sharp force trauma was inflicted around this time to prevent the miasma associated with the epilepsy spreading to the community," the international team of archaeologists propose.

"The woman was then buried in the prone position, further symbolizing her aberrant life and/or death."

It's a compelling theory, but it's still quite speculative and almost impossible to prove with the evidence at hand. No nails were left in the grave, but it's possible that a nail-like object ultimately caused the hole in the woman's skull.

In ancient Rome and Greece, humans burials are often found accompanied by nails, possibly as a spiritual way to keep the body in its grave, nailed to the past so it can no longer return to the world of the living.

The island of Sardinia at this time had its own culture, separate to the Roman culture, but it's possible that they had similar views on disease and shared burial traditions.

The face-down position of a corpse, for instance, might be a superstitious way to keep a dead person from coming back to life.

Sometimes in ancient Rome, corpses were placed face down as a punishment for harsh crimes. But that probably isn't the case with the woman in Sardinia.

Her remains were laid to rest in a tomb already occupied by another: a young teenager aged around 15 years. It's unclear if the two were related, but if the woman was being punished for sinful behavior, it's unlikely that she'd be buried alongside an innocent, or in a community graveyard for that matter.

Today epilepsy is known to be a relatively common condition in which waves of electrical impulses coursing through the brain produce seizures. Caused by genetic variations, trauma, infection, or even the body's own immune system attacking itself, the origins of epilepsy are diverse and often complex.

What is clear is it isn't at all related to a person's morals, beliefs, or cleanliness. Nor is it at all contagious. Thanks to centuries of insights and decades of advances in medical research, seizures can be limited if not eliminated by medication and, in some cases, surgery.

In his time, Pliny the Elder put forward numerous 'cures' for epilepsy, all of which sound absolutely laughable today: from the pricking of toes, to the touch of a virgin, to eating a bear's testes, or drinking a wild boar's urine.

Given that context, a nail to the head might not sound quite so strange after all.

The study was published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.