Visitors to the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC will now be greeted by the first-ever portrait of Henrietta Lacks, the young woman from southern Virginia whose cancer cells helped advance the course of modern medicine.

The National Portrait Gallery was founded in 1962 to celebrate all those who have contributed to the "history, development and culture" of the US. While the gallery contains many paintings of scientists, for over half a century, there was no portrait of the woman whose illness gave rise to the first immortal human cell line.

Making amends for the oversight, a painting of Henrietta Lacks now hangs in one of the main entrances to the museum. Bill Pretzer, a senior curator at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, told NPR it is proof "that history can be remade, re-remembered."

In 1951, Henrietta Lacks was undergoing treatment for cervical cancer when doctors took a tissue sample from her without her knowledge or consent. Henrietta, a poor mother of five children, did not survive the cancer, but the immortalised cell line derived from her tumour has been continuously cultivated by scientists to this day.

From the literal tons of cells produced, the HeLa cell line, as it is known, has come to aid some of the greatest scientific discoveries of our time, including the polio vaccine, AIDS drug research, and treatments for haemophilia, herpes, influenza and leukaemia.

Henrietta's cells were even on the first space missions, used in experiments to figure out what happens to human cells in zero gravity. Today, they are being used for research on Parkinson's and Ebola, and much more.

Yet for decades barely anyone knew Henrietta Lacks' name; none of her family have received any compensation for the ten thousand-some patents and the billions of dollars made from discoveries that used HeLa cells. In fact, her family didn't even know about the cell line until 1975.

The remarkable story has only recently come to public attention, thanks in large part to Rebecca Skloot's award-winning book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. After turning the story into a movie, HBO commissioned a portrait of Henrietta Lacks that was jointly acquired by the National Portrait Gallery and the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Now, as soon as you walk in to the portrait gallery, there she is. Her place of prominence is not only a correction for past injustice, but also a reminder of her continued impact, in both medicine and bioethics.

"Just like they said she was in life: happy, outgoing, giving — and she's still giving," her grandson, Jeri Lacks-Why, remarked at the unveiling in May, according to NPR.

(Kadir Nelson/Smithsonian)

(Kadir Nelson/Smithsonian)

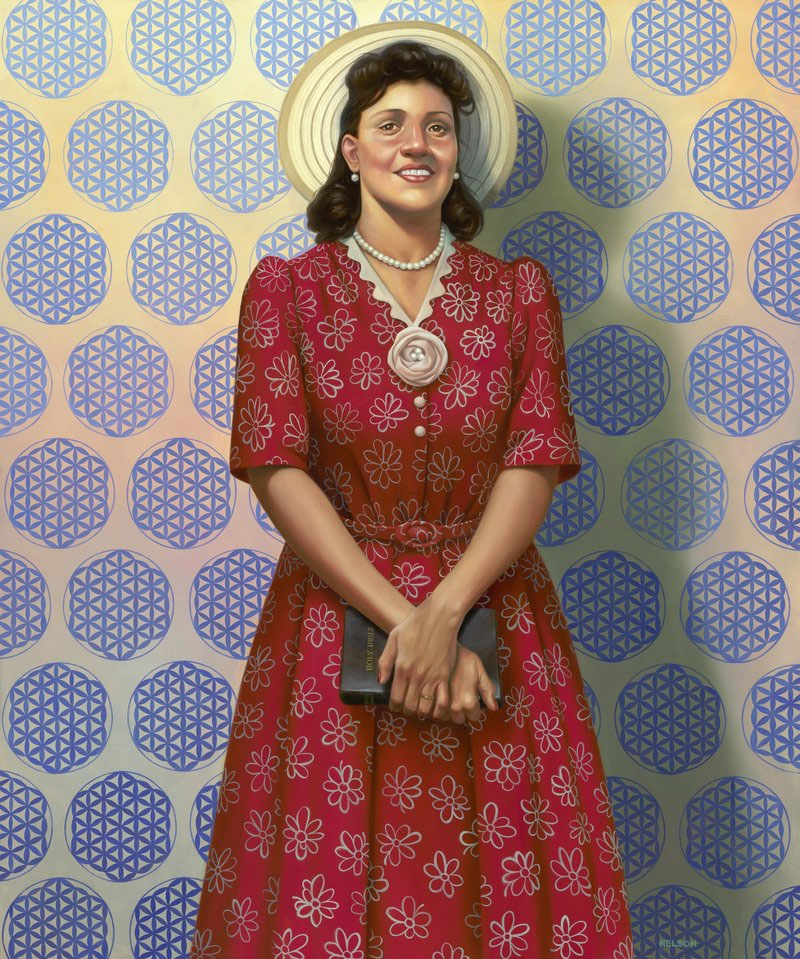

The painting by artist Kadir Nelson may appear bright and cheerful, but it is sprinkled with a darker meaning. In the portrait, Henrietta stands, smiling, with a bible covering the region of her body where the cells were taken from her.

Her bright red dress features a pattern reminiscent of cell structures, and the wallpaper's blue and purple hexagons resemble the "Flower of Life", a symbol of immortality.

Looking closer, you'll notice a couple of the buttons on Henrietta's dress are missing. These were left out by the artist to represent the cells that were taken from Henrietta without her consent.

Upon Henrietta's head is a straw hat mimicking a halo, and around her throat are pearls, reflecting the doctor's description of her studded tumours.

Yet, as with all art, interpretation is in the eye of the beholder. Henrietta's granddaughter, Kimberly Lacks, prefers a different explanation for the necklace.

"Pearls seem like it's classy, just a test of time - and that's what she was, she was classy," Kimberly said at the unveiling, according to NPR.

"I just think it's amazing. A great representation of our grandmother - our 'she-ro.' "

The museum hopes the portrait will spark a conversation about those who contribute to science, but are left out of history.

Science AF is ScienceAlert's new editorial section where we explore society's most complex problems using science, sanity and humor.