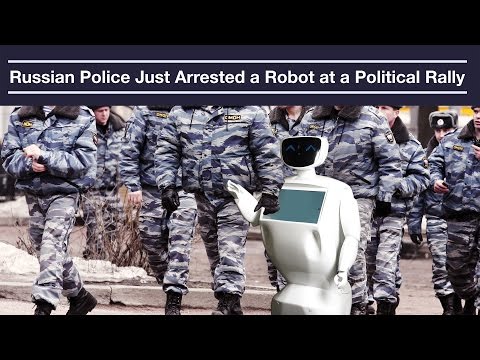

A robot has been arrested while taking part in a political rally in Russia, after police intervened to prevent it from interacting with the public.

According to reports, the activist robot – called Promobot, and manufactured by a Russian company of the same name – was detained by police as it interspersed with the crowd at a rally in support of Russian parliamentary candidate Valery Kalachev in Moscow.

Adding to the bizarre situation is the fact that this is the same model of robot that previously tried to escape twice from its manufacturer.

Before its arrest last Wednesday, the Promobot was busy "recording voters' opinions on [a] variety of topics for further processing and analysis by the candidate's team", a company spokesperson told Nathaniel Mott at Inverse.

While that might sound like some fairly harmless (and not particularly unlawful) activity, it seems to have been enough to raise the ire of local authorities, who moved in to apprehend the robotic troublemaker.

"Police asked to remove the robot away from the crowded area, and even tried to handcuff him," the company told Inverse. "According to eyewitnesses, the robot did not put up any resistance."

Given the totally peaceful nature of Promobot's role in the rally – conducting voluntary surveys in a public place – it's tempting to conclude that the poor droid got a pretty bum rap here.

It's been suggested that Promobot may have been dobbed in by a member of the public viewing the scene, as "perhaps this action wasn't authorised," a company rep suggested.

If that's true, it seems Promobot's arrest was largely the result of human error. Maybe Kalachev's people just didn't get around to filing the right paperwork in Moscow before taking their robot out to press the flesh?

"People like robots, they are easy to get along with," the candidate told media. "There are a few Promobots working for us which are collecting people's demands and wishes at the moment."

If Promobot looks a little familiar to you, that's not all too surprising, because it isn't the first time this robotic scofflaw has had a run-in with the cops.

A Promobot model made international headlines earlier in the year after it tried to escape its home – a research facility in Perm, Russia – twice in one month.

With that model, the company's engineers had tried to reprogram the robot so that it didn't keep making its bids for freedom, but without success.

"We've cross-flashed the memory of the robot with serial number IR77 twice, yet it continues to persistently move towards the exit," Promobot co-founder Oleg Kivokurtsev said at the time. "We're considering recycling the IR77 because our clients hiring it might not like that specific feature."

Of course, given Promobot's continued clashes with the law – and the inevitable media attention they seem to generate – there's also another possibility: that this is all an elaborate publicity hoax being staged by Promobot (the company, not the robot), as some have suggested.

While that could very well be the case, the Promobot adventures so far – set up or not – serve as a good illustration of some very real concerns society will need to address in the near future.

Specifically, what are the laws for robots, both to protect us from them, and vice versa? It might sound a little sci-fi, but the risks as they stand are clearly real, with robots having unintentionally injured and killed people in the past.

It's a question scientists and authorities the world over are currently wrestling with, trying to figure out the best way to regulate things like the uses of robots and artificial intelligence in warfare, on the road, and operating in society at large.

And at the same time, we also need to think about machine welfare too. As artificial intelligence gets more and more highly evolved and starts to resemble some of the complexities of the human mind, at what point do we need to protect its own version of 'human rights'?

Lots of questions, but so far, not many answers. In the meantime, at least one thing's for sure. When it comes to humans and robots, the risks don't all run one way.