As we get older, our brains start to change in ways that make them increasingly vulnerable to disease – and a detailed new study of these changes points to a way some of this wear and tear might be prevented or reversed.

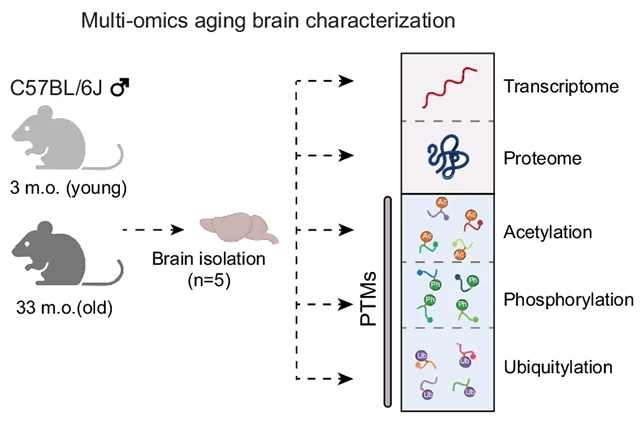

Researchers from the Leibniz Institute on Aging – Fritz Lipmann Institute in Germany used mass spectrometry to analyze the balance of brain proteins in both young and old mice, finding differences in a process called ubiquitylation as the animals aged.

Ubiquitylation adds chemical tags to proteins, telling the brain which of these busy molecules are past their peak and should be recycled. In older mouse brains, the ubiquitylation tags really start to pile up on certain proteins.

Related: Cheap Daily Supplement Appears to Boost Brain Function in Older Adults

"Our analyses have shown that aging leads to fundamental changes in how the proteins in the brain are chemically labeled," says molecular biologist Alessandro Ori.

"The ubiquitylation process acts like a molecular switch – it determines whether a protein remains active, changes its function, or is degraded."

Through further tests on human neurons grown in a laboratory from stem cells, the researchers determined that around a third of this accumulation was due to the slowing of the proteasome, the brain's protein-recycling system.

While scientists have long known that protein management and cleanup become less efficient as brains age, what's new is the detailed link to ubiquitylation and the gradual accumulation of tags that the proteasome should be acting on.

"This finely tuned system becomes increasingly unbalanced: many labels accumulate, and some are even lost, regardless of how much of a particular protein is present," says Ori.

The researchers also tried feeding older mice a calorie-restricted diet for four weeks before returning them to a normal diet to see if this would affect ubiquitylation. For some (but not all) of the proteins, this dietary intervention restored the chemical tagging to the state observed in younger animals when the normal diet was resumed.

While the researchers didn't study the underlying mechanisms in detail, the implication is that protein tagging in the brain – hugely important for brain health – can be adjusted through diet, even in old age.

Now, there are lots of caveats to consider – including that none of this has been tested in living humans yet – but the research takes us several steps forward in understanding some of the shifting processes that happen in the brain in later years.

That could be important in efforts to improve treatments for conditions where brain protein balance plays a role – including Alzheimer's.

Related: Scientists Pinpoint One Key Molecule Behind Exercise's Anti-Aging Power

The brain is an incredibly complex piece of biological machinery, making the study of it (and problems thereof) challenging. Even within this research, the observed changes weren't universal across all of the proteins and protein management processes in the brain.

"Our results show that even in old age, diet can still have an important influence on molecular processes in the brain," says Ori.

"However, diet does not affect all aging processes in the brain equally: some are slowed down, while others hardly change or even increase."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.