A world-first study has found almost nowhere left on Earth with consistently safe levels of air pollution.

The study, led by Monash University in Australia, found that only 0.001 percent of the world's population was exposed to low levels of air pollution in 2019; globally, 70 percent of days exceeded safe limits.

Air pollution causes around 8 million deaths each year. Tiny particles less than 2.5 micrometers in width (known as PM2.5) can invade the airways and blood vessels, causing strokes, lung cancer, and heart disease.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has set the safety threshold for daily PM2.5 exposure to 15 μg/m3, but between 2000 and 2019, the average level of air pollution across the globe was more than double that limit (32.8 µg/m3).

This study is the first to show the change in daily air pollution exposure globally over several decades. Data were drawn from 5,446 monitoring stations in 65 countries and processed using machine learning and simulations.

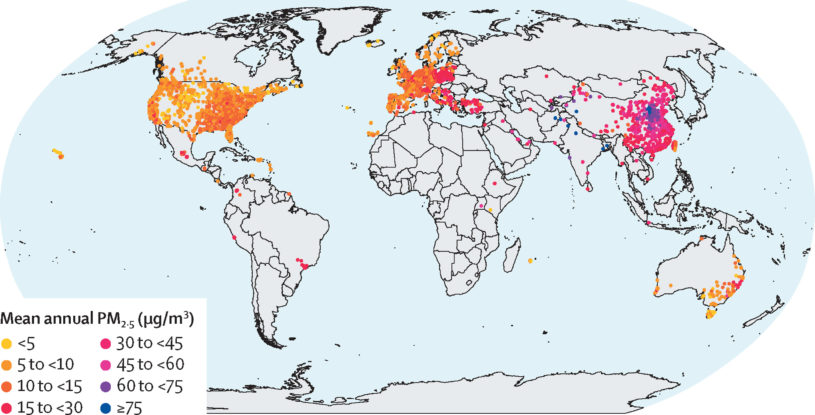

Eastern Asia had the worst air pollution over this two-decade period, with an average annual PM2.5 exposure of 50 μg/m3, followed by southern Asia (37.2 μg/m3) and northern Africa (30 μg/m3).

The regions with the lowest PM2.5 air pollution over two decades were Australia and New Zealand (8.5 μg/m³), other regions in Oceania (12.6 μg/m³), and southern America (15.6 μg/m³).

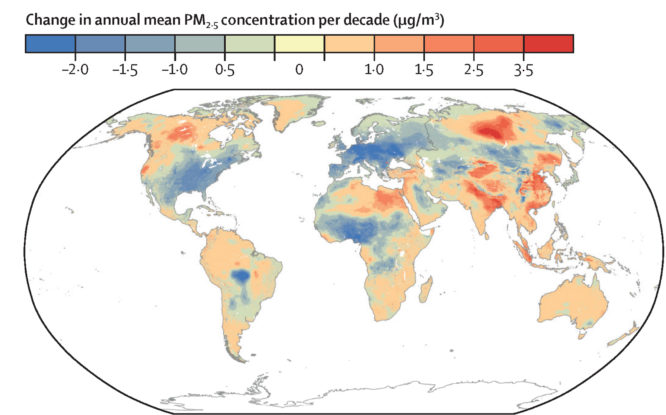

Air pollution decreased in Europe and North America between 2000 and 2019, but increased in southern Asia, Australia and New Zealand, South America, and the Caribbean.

Air pollution had a seasonal pattern. In northeast China and north India, using fossil fuels to heat homes created a peak in air pollution during winter. But the opposite pattern was seen on North America's east coast, where PM2.5 peaked in the summer months.

Climate change-related bushfires and dust storms may also have contributed to air pollution in south-eastern Australia in 2019, the researchers said.

"[This study] provides a deep understanding of the current state of outdoor air pollution and its impacts on human health," says Monash University air quality researcher Yuming Guo.

"With this information, policymakers, public health officials, and researchers can better assess the short-term and long-term health effects of air pollution and develop air pollution mitigation strategies."

PM2.5 pollution is created when fossil fuel combustion, car exhausts, wood fires, gas stoves, bushfires, or dust storms produce a toxic cocktail of nitrates, carbon, sulfates, lead, and arsenic that get suspended in the air.

When we breathe in these tiny particles, they pass through the lining of the lungs.

This can trigger inflammation, aggravating asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The toxic particles can pass into the blood vessels, causing them to inflame and restrict, which triggers strokes in some people. They can dislodge fatty plaque build-ups in the blood vessels, creating clots that damage the heart or brain.

This paper was published in The Lancet Planetary Health.