Astrophysicists are closer than ever to solving the mystery of what makes up almost 70 percent of the Universe.

A complete analysis of data from the full six-year run of the Dark Energy Survey has now been released, and it contains some tantalizing clues that suggest we might have it all wrong.

The Universe is not only expanding, but that expansion seems to be accelerating. Scientists aren't really sure why, so they've dubbed the unknown force " dark energy" and have spent decades trying to figure out what it actually is.

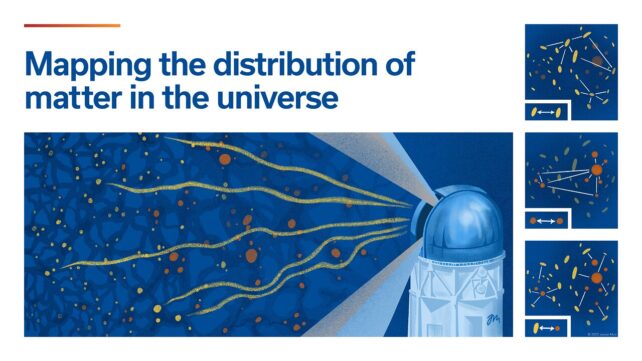

The most ambitious attempt to do so was the Dark Energy Survey (DES), an international collaboration that scanned a huge swathe of sky between 2013 and 2019. The mission used four different methods to measure the speed of the Universe's expansion at different points in its history.

Related: Our Universe Appears Lopsided, And It Could Break Cosmology Entirely

Those methods include baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO), which are ripples from the early epochs of the Universe; changes in the apparent brightness of Type Ia supernovae; the distribution of galaxy clusters; and how the light from distant galaxies is warped by the gravity of matter closer to us.

For the first time, the new analysis combines data from all six years and all four methods, giving us the most complete picture yet of how dark energy behaves.

The results are still consistent with the standard model of cosmology – but there are threads to pull that could unravel the whole mystery.

Currently, the model that best explains how the Universe functions is known as lambda-CDM. The lambda represents dark energy with a constant density over time, which accounts for around 68 percent of the cosmos's total energy.

"CDM" stands for "cold dark matter," which describes a hypothetical, invisible, slow-moving mass that would contribute about 27 percent of the Universe's energy.

The remaining five percent isn't deemed important enough to get a mention in the model's name. It is regular matter – you and I, Betelgeuse, whatever you had for breakfast, the Hercules-Corona Borealis Great Wall of galaxies, and everything in between.

But it's the lambda part of the equation that the DES was investigating. The new analysis tested whether dark energy has a constant density over time, as lambda-CDM predicts, or if it changes at different points, as described in an extended model called wCDM.

The analysis found that generally, DES observations lined up with the predictions of the standard model of cosmology.

However, they also fit the wCDM model, to a similar degree.

Intriguingly, it was also found that the way galaxies cluster in more recent times doesn't quite line up with predictions from earlier times, in either the lambda-CDM or wCDM models.

It's too early to say for sure if this means anything yet – the find is still a far cry short of five-sigma certainty – but more data could either cover the crack or open it up to reveal new physics.

The DES collaboration is already planning to use the new data to investigate how well alternative models fit, which could involve making tweaks to our understanding of how gravity itself works.

The new analysis is explored in a whopping 19 papers, with a summary submitted to the journal Physical Review D.