According to new research, communication between the gut and the brain is sophisticated enough to be classed as a new and distinct sense – one capable of affecting our appetite and even our mood.

This two-way link has previously been associated with a variety of health issues, though the physical processes at work have never been clearly identified.

Building on what we already know about our digestive and neurological systems, a team from Duke University in the US traced a series of biochemical actions from the digestive tracts of mice to their brains.

"We were curious whether the body could sense microbial patterns in real time and not just as an immune or inflammatory response, but as a neural response that guides behavior in real time," says neuroscientist Diego Bohórquez.

Related: Yo-Yo Dieting May Trigger Long-Lasting Changes in Gut Bacteria

For this study, the researchers looked closely at the protein flagellin, which is found in gut bacteria and already known to trigger immune system responses. What the team wanted to see was if flagellin could also send direct messages to the brain.

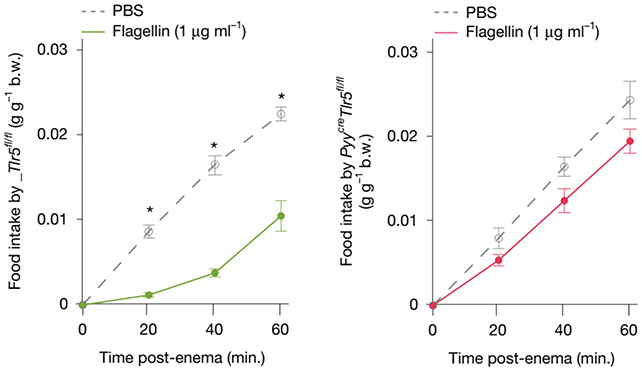

By giving mice small doses of flagellin after fasting, the researchers identified mechanisms connecting gut bacteria and the brain via colon cells called neuropods and the vagus nerve. These mice ate less than they normally would, with flagellin apparently acting as a type of messenger.

Further experiments showed that when the flagellin-sensitive receptors were turned off in mice, those animals kept on eating – further evidence that this signaling operated the way the researchers thought.

While it has previously been established that the brain's response to cues in the gut regulates our appetites, the researchers argue the fact gut bacteria trigger communication that is responded to in real-time through a complex series of mechanisms qualifies the process as a novel sense.

"This sense enables the host to adjust its behaviour in response to a molecular pattern from its resident microorganisms," write the researchers in their published paper.

"We call this sense at the interface of the biota and the brain the neurobiotic sense."

Further studies will be needed to confirm that this same sensing and signal processing is happening in humans, but there's a good chance that it is considering similarities between our digestive systems and those in rodents.

The study authors are keen to expand their research to look at other types of bacteria-driven communication between the gut and the brain that might be working in the background, and to analyze how these signals might change over time.

Further down the line – as with all research looking at how our guts and our brains are connected – the study may prove useful in understanding and treating eating disorders and obesity. Eventually, we might be able to control this distinct sense in beneficial ways.

"Looking ahead, I think this work will be especially helpful for the broader scientific community to explain how our behavior is influenced by microbes," says Bohórquez.

"One clear next step is to investigate how specific diets change the microbial landscape in the gut. That could be a key piece of the puzzle in conditions like obesity or psychiatric disorders."

The research has been published in Nature.