Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have the nickname 'forever chemicals' thanks to their persistence in the environment. While a handful of bacteria are known to mop up these insidious compounds, it's unclear whether any of our own microflora hide such a talent.

A new study by an international team of researchers has shown how several species of human gut bacteria can absorb and store PFAS. Potentially, boosting these types of bacteria in our bodies could stop the chemicals from negatively impacting our health.

"We found that certain species of human gut bacteria have a remarkably high capacity to soak up PFAS from their environment at a range of concentrations, and store these in clumps inside their cells," says Kiran Patil, a molecular biologist from the University of Cambridge in the UK.

"Due to aggregation of PFAS in these clumps, the bacteria themselves seem protected from the toxic effects."

Related: 'Game Changer': Hot New Tech Turns Forever Chemicals Into Valuable Resource

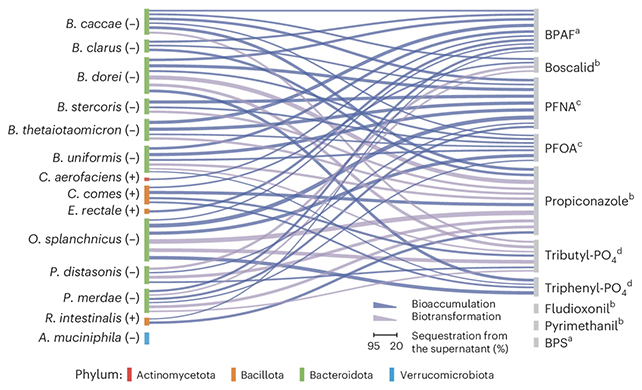

Through detailed lab tests, the researchers found a total of 38 different gut bacterial strains able to absorb forever chemicals at a variety of concentrations, with the fiber-degrading bacterium Bacteroides uniformis one of the best at the job.

In experiments with Escherichia coli, the team also discovered certain mechanisms that could make bacteria more or less effective at taking on board PFAS – something that will be useful if this absorption can be bioengineered in the future.

The researchers found that PFAS were effectively locked away in the bacteria that could handle the chemicals, the bacteria clustering together in a way that reduces their surface area and possibly protects the microorganisms from being harmed themselves.

Further tests on mice with nine of these bacteria species implanted in their guts showed that the microbes were able to quickly absorb PFAS, which was excreted from the mice through their feces. As levels of forever chemicals increased, the microbes worked harder at soaking them up.

"The reality is that PFAS are already in the environment and in our bodies, and we need to try and mitigate their impact on our health now," says molecular biologist Indra Roux from the University of Cambridge.

"We haven't found a way to destroy PFAS, but our findings open the possibility of developing ways to get them out of our bodies where they do the most harm."

PFAS are found in everything from cosmetics to drinking water to food packaging, and have become embedded in so many manufacturing processes that it would now be almost impossible to avoid them completely. What's less clear is the harm they might be doing to our bodies, though they've already been linked to a number of health issues – including kidney damage.

The bacteria's ability to remove PFAS from human bodies remains to be seen. It is possible, the researchers say, that probiotic dietary supplements may be developed to boost the right mix of gut microbes and help safely clear out PFAS from our systems.

"Given the scale of the problem of PFAS 'forever chemicals', particularly their effects on human health, it's concerning that so little is being done about removing these from our bodies," says Patil.

The research has been published in Nature Microbiology.