Sea anemones may look alien, but scientists just found out they're hiding an ancient body 'blueprint' – one that most animals, including humans, still follow. The discovery could shake up the timeline of evolution.

You might not be familiar with the term 'bilaterian,' although you are one. These are creatures with a body plan that's symmetrical along a single plane: from worms to whales, ants to elephants, and humans to hummingbirds.

Another major animal body plan is radial symmetry, meaning these creatures organize their bodies around a central axis. Picture a jellyfish, and then try to figure out which side is the 'front', and you'll likely understand.

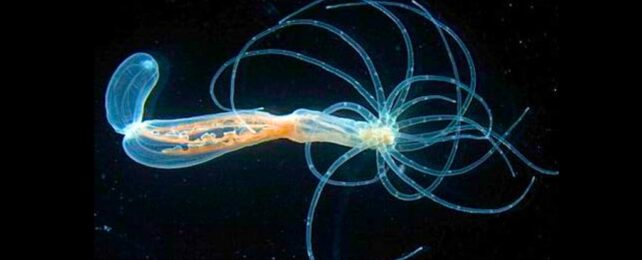

Most animals belonging to the cnidaria phylum, which includes invertebrates like jellyfish, sea anemones, and corals, have this body plan.

Related: New Discovery of Deep Sea 'Spiders' Is Unlike Anything We've Seen Before

But the categories aren't as neat as biologists might like them to be. Although it's a cnidarian, the sea anemone shows bilateral symmetry, which raises the question of when the feature evolved, and how many times.

To find out, researchers at the University of Vienna in Austria conducted experiments on starlet sea anemones (Nematostella vectensis) to see how they develop as embryos.

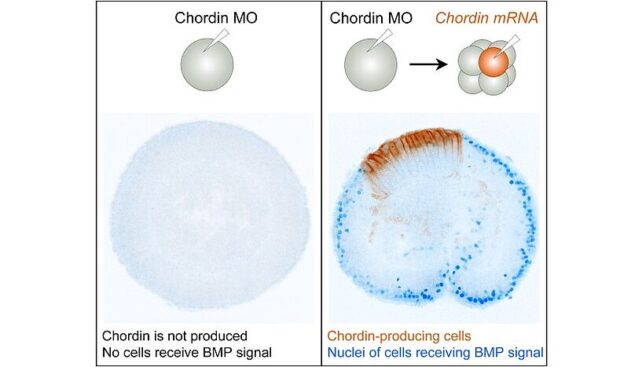

Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) is crucial to how bilaterians build their bodies. Essentially, a gradient of BMP tells developing cells what tissues they should become, based on where in the body they are.

In some bilaterians, like frogs and flies, this gradient is created thanks to another protein called chordin shuttling BMP around the body.

The team found that sea anemones also use this BMP shuttling mechanism. That suggests that the mechanism evolved before bilaterians and cnidarians diverged, more than 600 million years ago.

"The fact that not only bilaterians but also sea anemones use shuttling to shape their body axes tells us that this mechanism is incredibly ancient," says developmental biologist David Mörsdorf, first author of the study.

"It opens up exciting possibilities for rethinking how body plans evolved in early animals."

The research was published in the journal Science Advances.