A century or so before the pyramids graced the Egyptian horizon, around the same time as the erection of Stonehenge, hunters and gatherers half a world away were building megalithic stone structures to rival those of farmers.

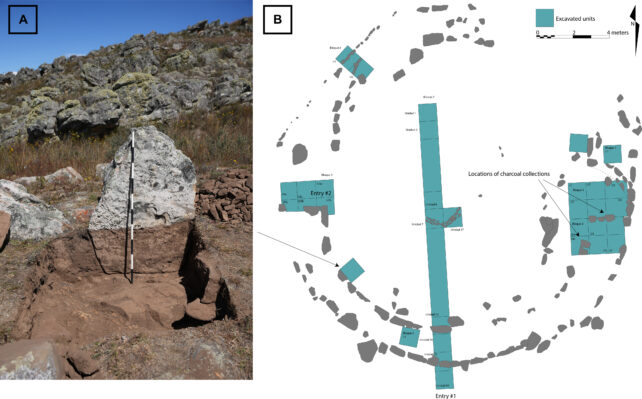

One of the earliest examples to date – an 18 meter (about 60 foot) wide circular plaza made from large upright stones – was recently excavated in a valley of northern Peru called Callacpuma.

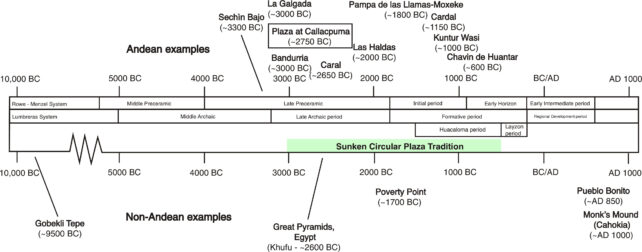

Findings from the ancient site, which was originally found nearly six decades before, now suggest that the plaza is around 4,750 years old. That makes it one of the oldest monolithic structures found in all of the Americas.

Not only was the monumental structure built before the true rise of farming in this region, it also predates technology like ceramics.

"In the northern highlands of Peru, the people that built the plaza at Callacpuma may have begun to experiment with food production, but they were also probably still relatively mobile hunter-gatherers," write the archaeologists behind the study.

The plaza may, therefore, be a long-lost meeting place of early nomadic societies, coming together to negotiate new group identities for the first time.

"[The Callacpuma plaza] is a critical early example of collective construction, place building, and social integration among people in the Andes," writes the team of researchers.

The remarkable site is bound by two concentric walls, constructed from unshaped and unmortared megalithic stones, each of which was probably chiseled out of exposed bedrock roughly 50 meters away.

Once these large and heavy slabs were transported to the site, the stones were tipped vertically and placed in close succession to one another. The circular structure they formed held two entrances and contained two or three rooms.

The style of architecture is rare for the region, archaeologists say.

Radiocarbon dating of charcoal found nearby suggests the plaza was used on occasion between 2632 and 2884 BCE, probably for religious or social purposes.

To bookend those dates for perspective, the Inca built Machu Picchu in the 15th century around 1450 CE and the Maya are thought to have built their earliest monoliths between 1050 and 750 BCE.

An older megalithic structure found on the Peruvian coast, called Sechin Bajo, contains a sunken plaza built around 3000 BCE. While older, this monument was made from stone-faced walls filled with cobbles and soil – a different architectural style.

The plaza at Callapcuma could be an offshoot of similar, early plaza-building traditions in the region. The site's discovery supports the emerging idea that farming is not necessarily required for human societies to build permanent, megalithic structures.

To assume that nomadic hunters and gatherers lack the incentive or skill to accomplish such feats is an outdated perspective that is facing growing scrutiny.

After all, the oldest known megalith in the world, called Göbekli Tepe, was built 11,000 years ago in what is now Turkey by a society of hunter-gatherers. Experts think these people probably came together at the site to farewell their dead or to stage sacred ceremonies.

"As with the case of early monumental collective architecture outside Andean South America, for instance at Gobekli Tepe," argue the researchers of the Callacpuma site, "the construction of monumental ritual architecture in the Late Preceramic of the coastal and highland central Andes represented a shifting social world perhaps involving a change from small group-related belief systems to more collective and regionally focused belief and action."

The circle of stones may not look like much today, but they tell an important story about humankind.

The study was published in Science Advances.