Scientists have announced the shock discovery in Germany of ancient teeth fossils that are nearly 10 million years old, and which they say don't fit in with our established timeline of human history.

What's causing a commotion is the researchers say one of these fossils is similar to that of humanity's primitive ancestors, hominins – except up until now, we've only seen teeth like this in Africa, not Europe, and even then, the existing fossil record is millions of years younger.

"This is not only the first time something like this has been found here in over 80 years, but it's something completely new, something previously unknown to science," palaeontologist Herbert Lutz from the Mainz Natural History Museum in Germany told ResearchGate.

The find, made near the German town of Eppelsheim in September 2016, uncovered two well-preserved teeth dated to about 9.7 million years ago.

Bastian Lischewsky

Bastian Lischewsky

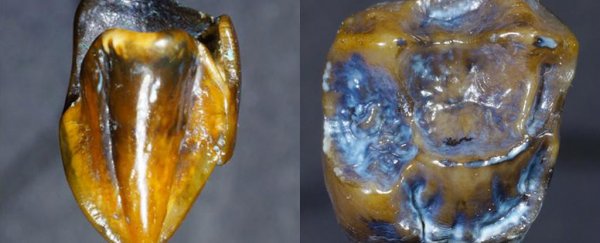

Historically, the Eppelsheim region is well-known for producing fossils, and one of these teeth, an upper right first molar, shares characteristics with other specimens discovered in the area.

But the other tooth, an upper left canine, is something else, and the researchers say its outline and shape give it close affinities with the teeth of hominin species including Australopithecus afarensis, the most famous example of which is a skeleton called Lucy.

The thing is, Lucy is estimated to only be a little over 3 million years old, and humanity's early ancestors are only thought to have begun their migration out of Africa and into Europe and Asia some 100,000 years ago.

So the question is: who did these teeth out of time and space belong to, and how in the name of human history did they get there?

"We've got two teeth from a single individual. That means there must have been a whole population," Lutz told ResearchGate.

"It wouldn't have been just one, all alone like Robinson Crusoe… if we're finding primate species all around the Mediterranean area, why not any like this? It's a complete mystery where this individual came from, and why nobody's ever found a tooth like this somewhere before."

The upper canine. Credit: Mainz Natural History Museum

The upper canine. Credit: Mainz Natural History Museum

The team thinks it's possible the species the teeth come from could be related to more recent hominins from Africa – in which case it means this mysterious and so-far-unknown group of primates existed in Europe before they were in Africa.

Alternatively, the upper canine similarities could be the result of convergent evolution – with the resemblance in shape to African hominin teeth being a genetic, environmental fluke, which just happened to arise in two different species in different locations.

"We want to hold back on speculation," Lutz said.

"What these finds definitely show us is that the holes in our knowledge and in the fossil record are much bigger than previously thought."

After holding off on publishing their research for more than a year while they continued their investigations – which are still ongoing – the team has now made their findings available in a pre-print.

But while news of the discovery has created significant headlines – no doubt assisted by the mayor of Mainz, who sensationally claimed "we shall have to start rewriting the history of mankind after today" – not everybody is convinced the findings are so dramatic.

For starters, a more likely explanation for the fossils is they belong to the broader primate group of hominoids, not hominins, which means they would be more distantly related to us than species like Australopithecus afarensis – and some commentators don't want to even go that far.

"I think this is much ado about nothing," palaeoanthropologist Bence Viola from the University of Toronto in Canada told National Geographic.

"The second tooth (the molar), which they say clearly comes from the same individual, is absolutely not a hominin, [and] I would say also not a hominoid."

Instead, it's possible the teeth belong to a much more distant group called pliopithecoids – something Lutz's team themselves acknowledge in their research.

But we won't know more about that for sure until the team have a chance to analyse the teeth in greater detail, which could tell them about the individual's age, dietary habits, and – maybe – its place in our ancient ancestors' story (or that of their cousins).

Until then, claims that we have to rewrite the textbooks need to be taken with a grain of salt, because the science on this one hasn't been fully cooked yet.

Watch this space.

The findings are reported in a pre-print available online.