A molten lava world cloaked in a thick envelope of vaporized rock could be the strongest evidence we have yet of a rocky exoplanet with an atmosphere beyond our Solar System.

The planet TOI-561 b is an ultra-hot super-Earth with what appears to be a global magma ocean beneath a thick atmosphere of volatile chemicals, according to a new study led by Carnegie Science researchers.

TOI-561 b is also an ancient astrophysical enigma that challenges what we thought we knew about searingly hot exoplanets trapped in a dizzingly fast dance around their stars.

Related: Astronomers Find an Astonishing 'Super-Earth' That's Nearly as Old as The Universe

The exoplanet orbits its star at a distance of less than 1.6 million kilometers (0.99 million miles), or just one-fortieth the distance between the Sun and Mercury, making it a tidally locked hellscape with one side bathed in eternal light and the other side plunged in perpetual darkness.

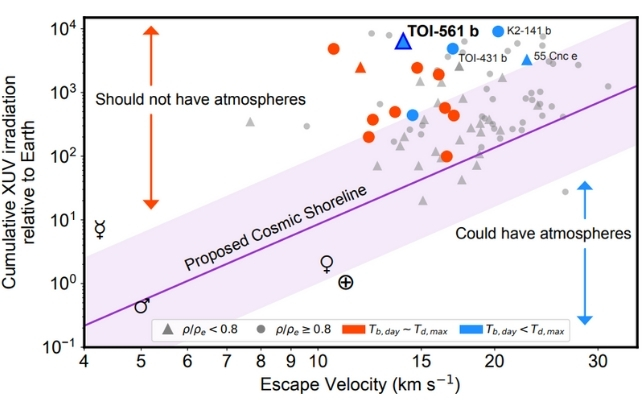

Curiously, it has somehow held onto its atmosphere for billions of years, despite the intense stellar irradiation that's thought to strip similar planets of their gaseous cloaks and leave them as naked, smoldering rocks, if not molten balls of lava.

"Based on what we know about other systems, astronomers would have predicted that a planet like this is too small and hot to retain its own atmosphere for long after formation," says Carnegie Science astronomer Nicole Wallack.

TOI-561 b is known as an ultra-short period (USP) planet due to its tight orbit, which takes fewer than 11 hours to complete. Size-wise, it is around twice the mass of Earth and 1.4 times Earth's radius.

It orbits an exceedingly elderly star that's slightly less massive and cooler than the Sun. This star is low in iron and rich in alpha elements like oxygen, magnesium, silicon, which were fused by massive stars in the early Universe.

It's also located in the Milky Way's thick disk, a galactic area akin to a stellar retirement community. These factors reveal the star to be around 10 billion years old, more than twice the age of the Sun.

Researchers also noted that TOI-561 b has an unusually low density, only about four times denser than water. That might be because TOI-561 b has a relatively small iron core and could be made of rocks that are less dense than those in Earth's crust, a composition that makes sense if TOI-561 b formed in the early Universe, when less iron was present.

On the other hand, it could also be because TOI-561 b has an atmosphere that makes it look larger than it actually is.

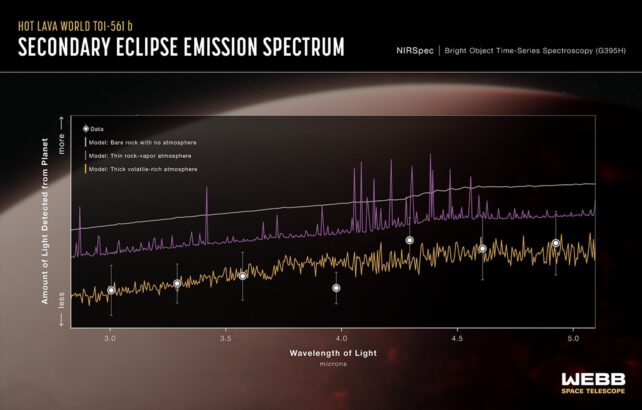

To ascertain whether TOI-561 b's lower-than-expected density was due to an atmosphere, the researchers used data from the JWST, which viewed the planet's system for 37 hours and nearly four full orbits around its star.

By measuring TOI-561 b's dayside brightness in near-infrared with Webb's NIRSpec (Near-Infrared Spectrograph), the researchers could calculate its temperature, and therefore whether it was likely to have an atmosphere.

Without an atmosphere, TOI-561 b should be around 2,700 degrees Celsius (4,900 degrees Fahrenheit), but the measurements showed it to be closer to a cooler 1,800 degrees Celsius.

The researchers speculate that an atmosphere could be 'cooling' the star-side of TOI-561 b in a few ways: Winds in an atmosphere may transport some of the heat from the dayside to the nightside, while water vapor could absorb near-infrared light from the planet's surface, making it appear colder.

But how has TOI-561 b managed to maintain this thick atmosphere for billions of years when flying so close to its host star?

The team thinks the exoplanet may have struck an equilibrium between its atmosphere and surface-covering magma ocean, which would have frozen solid on the nightside without an atmosphere.

Instead, the researchers think gases may have seeped from the exoplanet's crust to feed the atmosphere, with some unavoidably escaping into space. At the same time, the massive magma ocean may have been acting like a sink, drawing gases back into the planet's interior.

The exoplanet's iron content may play a role here: The same element that binds oxygen in our red blood cells may help TOI-561 retain its atmosphere by trapping volatile chemicals in its magma ocean or core.

"From the sample of rocky planets with dayside brightness temperature constraints, it appears that planets with irradiation temperatures exceeding ∼2000 K are able to replenish volatile envelopes faster than they are lost," the researchers write in their paper.

However, "pinpointing exactly why TOI-561 b has a thick atmosphere will require further theoretical and observational investigation."

This research is published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.