It's the midst of winter in the Southern Hemisphere and Antarctica is missing an obscene amount of ice.

"One might think that the huge remote continent of Antarctica with its kilometers-thick ice sheet could withstand extremes brought about by climate change, but this is absolutely not the case," says University of Leeds glaciologist Anna Hogg.

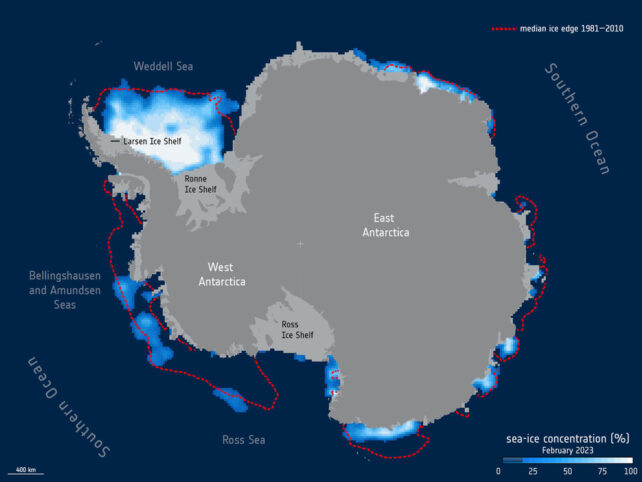

The missing sea ice is currently the size of Greenland, a country that spans nearly 2.2 million square kilometres (836,330 square miles).

As a six sigma event, it should only occur once in 7.5 million years. But times are changing. New research led by University of Exeter geophysicist Martin Siegert suggests such extremes are now virtually certain to continue.

The rate of #Antarctic sea ice growth has slowed down even more in the last few days...

— Zack Labe (@ZLabe) August 12, 2023

More visualizations at: https://t.co/V0Lt0w1sTi. More information on this extreme event at: https://t.co/4QzBhL1jQc and https://t.co/IVqbfh3zrH. pic.twitter.com/VCccaWjD0u

Reviewing changes in Antarctic atmosphere, weather, ice and the response from wildlife, Siegert and colleagues note concerning signs that many of these changes are now locked in. Particularly since we've now already added enough fossil-fuels to the atmosphere to hit the 1.5 °C Paris limit, and we're not yet even experiencing the impacts of about 0.4 °C (0.7 °F) of that yet.

For example, on top of the missing sea ice, last year Antarctica experienced the most extreme heat wave on record, reaching 38.5 °C (69.3 °F) above its average temperature.

"It is virtually certain that continued greenhouse gas emissions will lead to increases in the size and frequency of events," Siegert and team write in their paper.

This is because Antarctica's ice plays a massive role in keeping Earth cool. Its highly reflective white surface doesn't absorb sunlight, so the huge loss of ice we're witnessing means a big chunk of sunlight is now no longer being reflected back into space, triggering even more heating.

This guarantees increasingly extreme weather events and rising seas.

"Ice shelves are important because they provide buttressing support that stabilizes the rate of flow from the ice sheet on land," says Siegert.

"When ice on land is lost to the sea, it adds to sea-level rise."

The icy continent also shapes global ocean and atmospheric currents and we don't yet understand the full ramifications of messing with those.

"The feedback loops involved in the climate system are very complex and we still have much to learn," explains Hogg. "Satellites orbiting Earth such as the Copernicus Sentinel-1, ESA's CryoSat and missions to be launched in the future, are vital for measuring and monitoring this remote part of our world."

However the researchers conclude it is now "highly likely that with continued high levels of greenhouse gas emissions global sea level may increase by more than 1 meter this century and much more thereafter."

The review echoes a spate of recent studies and events all demonstrating climate consequences are happening faster than previous estimates.

And all this is only at 1.1 °C of heating. We're on track for much more.

Politically, physically, socially, the world is going to be unrecognisable within ten years. Beyond all our imaginations if we are honest. Either for the better or the worse. Up to us. But it’s physically impossible that it will continue as is. 🎲 #ClimateAction pic.twitter.com/6WJYhquTHN

— Matthew Todd 🌏🔥 (@MrMatthewTodd) August 10, 2023

"Antarctic change has global implications," says Siegert. "Reducing greenhouse gas emissions to net zero is our best hope of preserving Antarctica, and this must matter to every country – and individual – on the planet."

Researchers are understandably frustrated as their warnings continue to be ignored.

"We've been saying this for 30 years," University of Colorado glaciologist Ted Scambos, who was not involved in the new research, told Melina Walling at Japan Today. "I'm not surprised, I'm disappointed. I wish we were taking action faster."

The research is published in the journal Frontiers in Environmental Science.