At an average altitude of around 1,800 metres (1.1 miles), high in the Jotunheim Mountains of Norway, a patch of ice is melting. It's called the Lendbreen ice patch, and for millennia, it has been frozen year-round, accumulating a new layer every year.

But in the past two decades, the ice has been slowly melting as the climate grows progressively hotter. This melting of permanent ice is occurring around the world - but in the case of Lendbreen, the melting ice is like Santa Claus for archaeology.

As the Lendbreen ice patch recedes, it's revealing an absolute treasure trove of artefacts, some of which have been buried under the ice for thousands of years.

After a careful study of these objects, archaeologists have now confirmed that the region was once a heavily trafficked mountain pass around a millennia ago - and not just a pass. The presence of horseshoes and other travel accoutrements indicates the region could have once been a bustling (for the time) Viking highway.

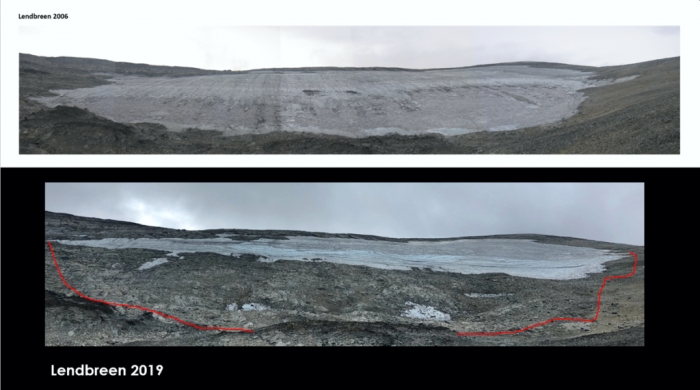

The ice patch in 2006 (top) and 2019 (bottom). (Espen Finstad/secretsoftheice.com)

The ice patch in 2006 (top) and 2019 (bottom). (Espen Finstad/secretsoftheice.com)

Not all the artefacts have been studied yet, but the radiocarbon dating conducted on around 60 objects so far shows that the region was well trafficked during the Middle Ages, before becoming forgotten following the Black Plague that wracked Europe in the 14th century.

"Artefacts exposed by the melting ice indicate usage from c. CE 300-1500, with a peak in activity c. CE 1000 during the Viking Age - a time of increased mobility, political centralisation and growing trade and urbanisation in Northern Europe," the team writes in their paper.

"Lendbreen provides new information concerning the socioeconomic factors that influenced high-elevation travel, and increases our understanding of the role of mountain passes in inter- and intra-regional communication and exchange."

Over the years, a few artefacts had been discovered in the region. In the 1970s and 1980s, some were reported and turned in to local archaeologists, including a spectacular Viking Age spear discovered in 1974.

A bit for a kid or lamb. (secretsoftheice.com)

A bit for a kid or lamb. (secretsoftheice.com)

The summer of 2011 was extremely warm, resulting in a huge melt that exposed a plethora of artefacts. Archaeologists returning to the region from the previous year were shocked at the melt - and scurried to collect and catalogue the history littering the newly exposed ground before snows returned to cover it all up again.

They returned every year until 2015, and again in 2018 and 2019, collecting hundreds of artefacts over a site that covered 250,000 square metres - the size of 35 football fields, of icy, rocky scree and punishing conditions.

"It has been a demanding fieldwork, in often appalling weather conditions," wrote archaeologist Lars Pilø of the Innlandet County Council in a blog post.

"However, the reward has made it all worthwhile. The results from the fieldwork have made it clear that we have indeed discovered a lost mountain pass - the dream site for glacial archaeologists."

This exceptional blue textile dates back to the 10th century CE. (secretsoftheice.com)

This exceptional blue textile dates back to the 10th century CE. (secretsoftheice.com)

The glacial ice preserves all kinds of organic materials that would otherwise be lost to weathering. Objects of leather, bone, wood, and wool have been uncovered in excellent condition, giving us a rare glimpse into the everyday lives of the people moving through the Jotunheim Mountains over the centuries.

Objects include shoes, mittens and clothing, even a complete wool tunic dating back to the third century CE; a wooden tinderbox; sleds and parts of sleds; a wooden whisk that could have doubled as a tent peg; a small knife; and a small bit, carved from juniper, likely used to keep young goats and lambs from suckling, thus ensuring a supply of milk for human consumption.

But it was the presence of horseshoes - including a snowshoe made to fit a horse's hoof - that provided clues that the region was a road. And then the team discovered cairns, distinctive piles of stacked rocks. These have been used repeatedly throughout history as waymarkers for travellers, to prevent people from losing their path.

A horse snowshoe. (Espen Finstad/secretsoftheice.com)

A horse snowshoe. (Espen Finstad/secretsoftheice.com)

"It is now clear that Lendbreen was a focal point for regional transhumance and probably also long-range travel starting during the Roman Iron Age (CE 1-400) through until the end of the Middle Ages (CE 1050-1537)," the researchers wrote in their paper.

"The site's exceptionally rich archaeological material illustrates a long-lived transhumance system in seasonally changing mountain terrain, and provides a model pertinent to the study of mountain passes globally. Such passes played key roles in past mobility, facilitating and channelling transhumance, intra-regional travel and long-distance journeys."

The ice that covered the Lendbreen pass is likely all melted by now; 2019 was the last archaeological season on the site. But there is still more work to be done. The new paper only covers artefacts discovered up to and including 2015. There's a great deal more to be tested and analysed.

And the ice patch has shown that these melting regions can be incredibly rich time capsules. The team is already casting their eyes to other sites.

"Just after finishing work at Lendbreen in 2019, finds started melting out in a mountain pass further west on the ridge," Pilø wrote.

"During a quick survey on the last day before winter snow arrived, we managed to recover an Iron Age shoe and a piece of leaf fodder here. There will be more to come."

The research has been published in Antiquity.