Some of the oldest evidence of humans modifying the shape of their skulls has just been uncovered in what is now northeastern China. Up to 12,000 years ago, people who lived there were intentionally reshaping their heads - and the practice continued for thousands of years.

In tombs at the Neolithic Houtaomuga archaeological site in Jilin, archaeologists recovered 25 skeletons, 11 of which showed evidence of intentional cranial modification - or, as it's more commonly known, artificial cranial deformation - dating from between 12,000 and 5,000 years ago.

Although it's dying out today (you can see some fascinating examples of it here), it's an ancient practice, and there's evidence for it dating back thousands of years all around the world.

The earliest known example of this practice was thought to be of two Neanderthal skulls in Iraq that date back around 45,000 years ago. Published in 1982, that finding has since been called into question, but archaeologists are more confident in other skulls dating back to 13,000 years ago in Australia.

But, prior to the Houtaomuga discovery by archaeologists at Jilin University in China and Texas A&M University, no other archaeological site had provided evidence for skull shaping that spanned a massive timeframe of 7,000 years.

The skulls of two 8-year-old children, unmodified (left) and modified. (Zhang et al., American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2019)

The skulls of two 8-year-old children, unmodified (left) and modified. (Zhang et al., American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2019)

"The area as part of the Northeast Asia has arguably served as a centre for the radiation of human populations to territories beyond northern China, such as central China, the Korean Peninsula, the Japanese archipelago, eastern Siberia, and possibly the American continents," the researchers wrote in their paper.

"Therefore, the new materials found at the Neolithic Houtaomuga Site in Northeastern China may hold secrets about the origin, diffusion, and meaning of intentional cranial modification."

Cranial modification is usually performed in infancy, when the baby's skull is still quite soft and malleable, the bones not yet fused. The head can be wrapped tightly with cloth, or shaped with boards, so that it grows in a flattened, elongated shape, somewhat resembling Ridley Scott's xenomorph.

Curiously, this seems to have no negative impact on cognitive function.

We can't know exactly why the Houtaomuga people performed it, and over millennia it's possible there were a number of different motivations. In addition, reasons for the practice seem varied globally throughout history - from a marker of social status, to a side-effect of binding a baby's soft head to protect it while it grows.

The site was excavated between 2011 and 2015, during which time it yielded 25 individual skeletons. Only 19 of these had skulls in good-enough condition to examine. CT scans revealed that 11 skulls showed signs of modification.

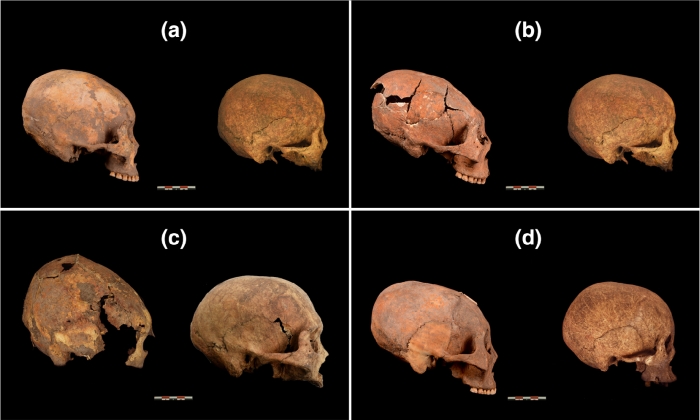

(Zhang et al., American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2019)

(Zhang et al., American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2019)

Above: Four intentionally modified adult skulls, on the left of each box, compared to nonintentionally modified skulls.

They were five adults (four men and one woman), and six children, with ages ranging between around 3 to 40 years.

The oldest was an adult male, radiocarbon dated to around 12,000 years ago. The others were from two layers of sediment, one from 6,500 years ago and the other from 5,000 years ago.

"We noticed that not all individuals carried the sign of intentional cranial modification, indicating that it might be a selective intentional cultural behaviour among this population," the researchers wrote.

All the burials were placed in the same type of vertical tomb, and there seemed to be no sex-based preference for modified skulls. Some of the burials - in particular the three-year-old child and the adult woman - were buried with opulent grave goods, generally an indicator of high status.

There were also two shared tombs, one with an adult and child, and another with three individuals. The adult and child buried together both showed signs of modification, but the three-person tomb did not; this could mean that sometimes there was a familial element to it.

"All of this evidence indicates that among the whole population, the practice of intentional cranial modification was a type of cultural practice only implemented on certain individuals," the researchers wrote.

"Although the selective criterion and meaning of this cultural behaviour are still unknown, the distinction of identity, perhaps depending on family affiliation or socioeconomic status, should be principle reasons for the cranial modification."

Further research will be conducted to compare the Houtaomuga site to other Neolithic sites around the area to try to learn more about this curious practice.

The research has been published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology.