Galaxy mergers are not particularly rare, but they are important events. Not only for the galaxies involved, but for scientists trying to piece together how galaxies evolve. Now, astronomers using ALMA have found the earliest example yet of merging galaxies.

The pair of merging galaxies in question is called B14-65666, an unwieldy name, but scientifically useful. (For now we'll refer to it as "the object.") The object is 13 billion light years away, in the constellation Sextans.

That means that the light we're seeing now left the object 13 billion years ago, shortly after the beginning of the Universe.

This isn't the first time this object has been spotted. Previously, the Hubble spotted this object, but it appeared to the Hubble as two separate objects, probably star clusters.

But the team using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), perhaps the world's most sensitive radio telescope, has shown that the object is in fact two merging galaxies 13 billion years ago.

The results of these new observations are published in Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan on June 18, 2019. The name of the paper is "Big Three Dragons': a z = 7.15 Lyman Break Galaxy Detected in [OIII] 88 um, [CII] 158 um, and Dust Continuum with ALMA." Lead author of the study is Takuya Hashimoto from Waseda University, Japan.

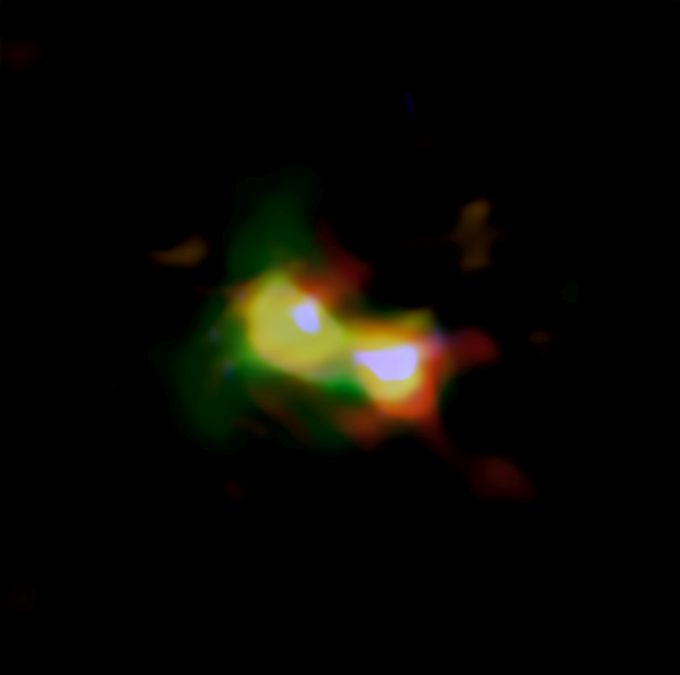

When Hubble looked at the object, it was limited to the ultraviolet spectrum. With that restriction, the object appeared to be two star clusters, one in the northeastern and one in the southwestern.

But when Hashimoto and his team used Alma's power to study the object, they saw something else: the telltale fingerprints of chemical elements.

ALMA was able to see the radio wave emissions of carbon, oxygen, and dust in the object. The detection of those three signals was the key to unlocking the object's nature.

Analysis showed that the object does indeed have two parts, just like Hubble saw. But the signals from carbon, oxygen, and dust added another layer of information on the object, thanks to ALMA.

It showed that while the two blobs are distinct, they form a single system. Each blob is moving at a different speed, which shows that they are two galaxies merging.

"With rich data from ALMA and HST, combined with advanced data analysis, we could put the pieces together to show that B14-65666 is a pair of merging galaxies in the earliest era of the Universe," explains Hashimoto in a press release.

"Detection of radio waves from three components in such a distant object demonstrates ALMA's high capability to investigate the distant Universe."

According to the study, the object is now the earliest-known example of a galaxy merger. The researchers also estimated the total stellar mass of B14-65666 as less than 10 percent of the Milky Way's mass. This means that the object is in the earliest stages of its evolution. This makes sense, since it is ancient.

(NASA/ESA)

(NASA/ESA)

Even though the object is young, it's much more active in star production than our own galaxy is. ALMA observations detected high temperatures and brightness in the dust. The authors say that's probably a result of very powerful ultraviolet radiation produced by active star formation.

That active star formation is another indication of merging galaxies, because colliding galaxies undergo a lot of gas compression, which triggers bursts of star formation. As the authors say in their paper, "…we argue that B14-65666 is a starburst galaxy induced by a major-merger."

"Our next step is to search for nitrogen, another major chemical element, and even the carbon monoxide molecule," said Akio Inoue, a professor at Waseda University, and part of the research team.

"Ultimately, we hope to observationally understand the circulation and accumulation of elements and material in the context of galaxy formation and evolution."

Galaxy mergers are an important part of the evolution of galaxies. Often, a larger galaxy swallows a smaller one. Small galaxies can merge to form larger ones, though that's thought to be rare. Our very own Milky Way has experienced mergers which helped it grow to its present enormous size.

In a 2018 paper, astronomers presented evidence based on a century of observations showing that the Milky Way contains a population of stars from a different galaxy.

Roughly ten billion years ago, another galaxy collided with our own, leaving behind a distinct population of stars in the galactic inner halo. The authors of that paper argued that those stars are from a small galaxy that was roughly the size of the Small Magellanic Cloud.

In about 4.5 billion years, the Milky Way will collide with the Andromeda Galaxy and merge. The resulting galaxy will be called, possibly, Milkdromeda. And right now, the Milky Way is merging with, or eating, the much smaller ghost galaxy called Antlia 2 (Ant 2).

The authors of the study think that, much like our Milky Way, there may be more mergers in the objects future (past?) that are so far undetected. In the paper they say, "Although our current data do not show companion objects around B14-65666, future deeper ALMA data could reveal companion galaxies around B14-65666."

They conclude that the object is a prime candidate for follow-up observations. "Given the rich data available and spatially extended nature, B14-65666 is one of the best targets for follow-up observations with ALMA and the James Webb Space Telescope…"

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.