Sometimes the most amazing discoveries can happen just by chance. Case in point: an international team of astronomers accidentally photographed what they think is a planet in the process of growing bigger, 600 light-years away.

The star in question is a binary called CS Cha, located in a star-forming region in the southern constellation of Chamaeleon. It's a T Tauri star - very young, only 2 to 3 million years old, the perfect age to be surrounded by a protoplanetary disc of dust and gas, in the process of forming planets.

It was just such a disc that the research team, led by Dutch astronomers from Leiden University, was hoping to find when they studied the star using the Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch (SPHERE) instrument on the Very Large Telescope in the Chilean desert in February 2017.

CS Cha has what is known as a circumbinary disc, which surrounds both stars in the binary system.

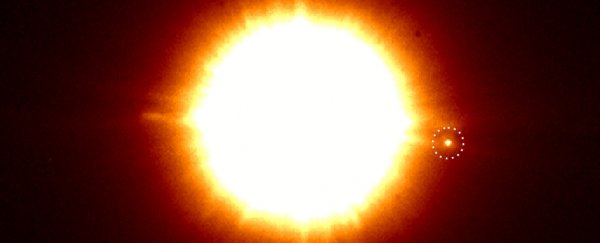

But when they were looking at the images, the researchers saw a small dot of light near the binary, outside the circumbinary disc.

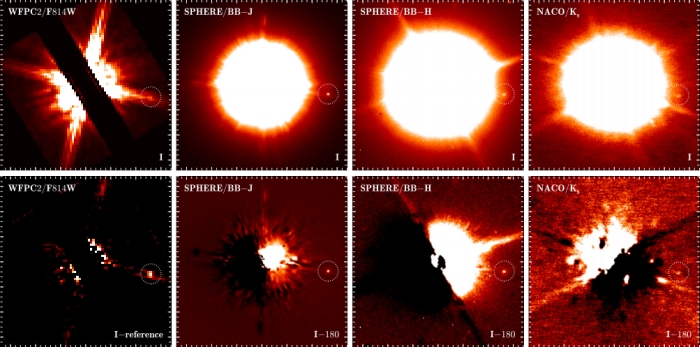

Images from the different instruments showing CS Cha's companions. (Ginski et al.)

Images from the different instruments showing CS Cha's companions. (Ginski et al.)

When they looked at images taken by the VLT's NACO instrument 11 years ago, they saw the dot again. And again in photos taken by the Hubble Space Telescope's Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 19 years ago.

So it wasn't a glitch, or a transient anomaly - it was something that was really there persistently over time.

And it was moving with CS Cha - it's definitely a companion to the binary star.

Now, the researchers don't know with certainty what it is, yet. The options are relatively limited for a visible object orbiting a star. It could be a brown dwarf, a type of very low mass "failed" star too small to sustain hydrogen fusion, but too big and too hot to be categorised as a gas giant.

It could, however, also be a large gas giant that's still growing, what is referred to as a super- Jupiter.

Spectroscopic analysis to try and figure out which has proven difficult, but the reason why has the research team intrigued.

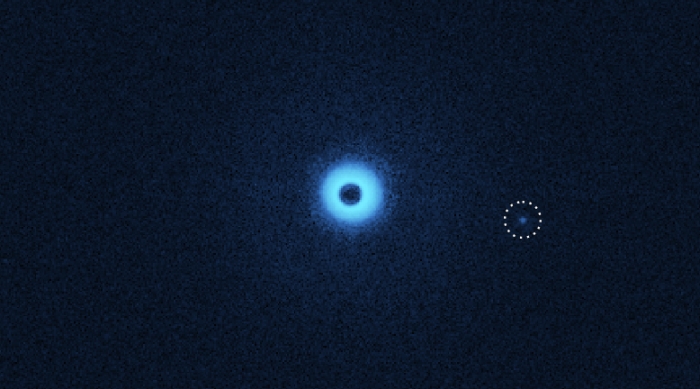

"The most exciting part is that the light of the companion is highly polarised. Such a preference in the direction of polarisation usually occurs when light is scattered along the way," explained astronomer Christian Ginski of Leiden University, lead author on the new paper.

"We suspect that the companion is surrounded by his own dust disc. The tricky part is that the disc blocks a large part of the light and that is why we can hardly determine the mass of the companion.

"So it could be a brown dwarf but also a super-Jupiter in his toddler years. The classical planet-forming-models can't help us."

Infrared image of CS Cha and its companion, polarised to make the dust disks visible. (C. Ginski/SPHERE)

Infrared image of CS Cha and its companion, polarised to make the dust disks visible. (C. Ginski/SPHERE)

If it's either of one of those two things, the find will be an extraordinary one. Most exoplanets are too far away to be photographed directly.

We can only infer their presence based on the way they change the light of their host star, whether they dim it as they pass between it and our telescopes, or if the tug of their gravity ever so slightly changes the star's position in the sky, leading to a Doppler shift.

The list of exoplanets that have been directly observed is incredibly short, and the first direct observation of a possible brown dwarf was only announced in 2009, a discovery that researchers were deeply excited about.

"Brown dwarf companions to solar-type stars are extremely rare," researcher Michael McElwain of Princeton University told Space.com at the time.

Never mind one with its own disc.

Ginski's team is going to be working to find out exactly what their object is using the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array in Chile.

"The CS Cha system is the only system in which a circumplanetary disc is likely present as well as a resolved circumstellar disc. It is also to the best of our knowledge the first circumplanetary disk directly detected around a sub-stellar companion in polarised light, constraining its geometry," the researchers wrote in their paper.

"Once the system is well understood it might be considered a benchmark system for planet and brown dwarf formation scenarios."

The research has been accepted for publication in Astronomy & Astrophysics, and can be read in full on preprint resource arXiv.