The discovery of a giant, ghostly circle in extragalactic space is bringing us closer to understanding what these mysterious structures actually are.

The so-called odd radio circle, named ORC J0102-2450, joins just a handful of previously discovered space blobs. Given the low sample size, the new discovery adds important statistical data that suggest these objects could somehow be related to galaxies. The paper has been accepted into MNRAS Letters, and is available on preprint server arXiv.

Humanity has been staring up and wondering about the sky for tens of thousands of years, but even so, space retains many secrets. Odd radio circles - ORCs - were only discovered last year, in 2019 observations collected by the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP), one of the world's most sensitive radio telescopes.

As the name suggests, they're apparently giant circles of relatively faint light in radio wavelengths, appearing brighter around the edges, like bubbles. Although circular objects are relatively common in space, the ORCs seemed to correspond with no known phenomenon.

Follow-up observations with a different telescope array confirmed the presence of two of the original three ORCs, while a fourth was soon found in data collected by yet another instrument. So, we can be pretty confident these aren't the result of some ASKAP glitch or artifact, or a phenomenon local to the telescope (like the Murriyang microwave oven) either.

We don't know how far away the ORCs are, which makes their size hard to gauge, but finding more of them could give us more clues. That's where ORC J0102-2450 enters the picture.

ASKAP conducted a series of radio continuum observations between 2019 and December 2020. To find the ORC, a team led by astronomer Bärbel Koribalski of CSIRO and Western Sydney University in Australia combined eight of the radio continuum images, a process that reveals objects too faint to be seen in just one or two images.

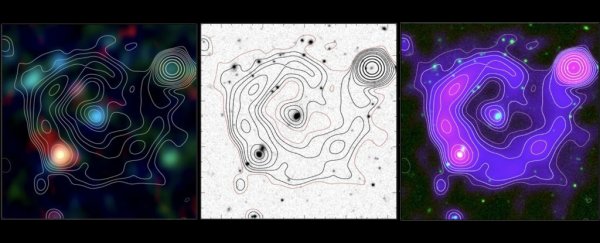

From the combined data, a faint ring emerged. Comparison with observations from other surveys revealed no radiation in other wavelengths than radio, which can help rule out some sources of the emission.

Interestingly, however, almost bang in the center of the ORC, the team found something: an elliptical radio galaxy, named DES J010224.33-245039.5.

Sure, this could be a coincidence - but two of the other four ORCs described last year also had an elliptical radio galaxy bang in the middle. The probability of finding a radio source randomly coincident with the center of an ORC is one in a couple of hundred, the researchers said - never mind finding three of the things.

This suggests that the circles may have something to do with elliptical radio galaxies. We know that radio galaxies often have radio lobes, huge elliptical structures that only emit in radio wavelengths ballooning out on either side of the galactic nucleus. One possibility is that the ORCs are these lobes viewed end-on, so that they appear circular.

The ORCs could also, the researchers noted, be the product of a giant blast wave from the central galaxy, but it would have to be truly giant, produced by something like the merger of two supermassive black holes.

If either of these scenarios is the case, the link with the galaxy can help us work out the size of the ORC. In the case of ORC J0102-2450, we know the distance to DES J010224.33-245039.5. That distance gives us a rough size estimate for ORC J0102-2450 of around 980,000 light-years. If this size is confirmed, it could help us to learn more about radio lobes or blast waves.

The third possibility the researchers considered is an interaction between a radio galaxy and the intergalactic medium, possibly involving DES J010224.33-245039.5, although this seemed relatively unlikely to be able to produce the observed ring, the team noted.

Although the sample size is still extremely small, and we can't tell anything for sure just yet, the discovery of ORC J0102-2450 points to some promising directions for future observation and analysis.

If we can find even more ORCs, they should be able to help astronomers determine how common they are, and find more similarities between them that could further narrow down their potential formation mechanisms.

Low-frequency radio observations and X-ray observations will be of particular interest, they noted.

"The discovery of further ORCs in the rapidly growing amount of wide-field radio continuum data from ASKAP and other telescopes will show if the above scenarios have any merit, contributing to exciting times in astronomy," the team wrote in their paper.

The paper has been accepted into MNRAS Letters, and is available on arXiv.