An international team of astronomers has announced the discovery of a new dwarf planet in our Solar System, finding a distant object beyond Neptune that circles the Sun in a spectacularly wide orbit.

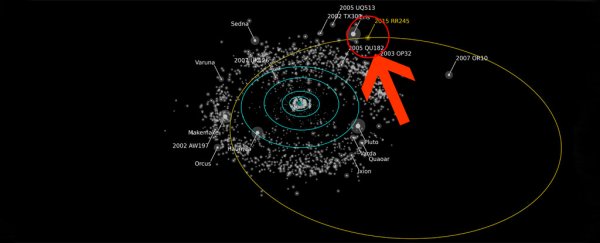

Dubbed 2015 RR245 by the International Astronomical Union while they come up with a better name, the dwarf planet is about 700 kilometres in diameter, and its elongated orbit sends it out some 120 times further from the Sun than Earth. So it's a pretty distant neighbour.

Astronomers are finding more of these dwarf planets in the Kuiper belt all the time, but even so RR245 stands out for its size and orbit. In fact, the scientists who found it – as part of the Outer Solar System Origins Survey (OSSOS) – say it's the largest OSSOS discovery to date, of more than 500 trans-Neptunian objects identified by the Survey.

"The icy worlds beyond Neptune trace how the giant planets formed and then moved out from the Sun. They let us piece together the history of our Solar System," said researcher Michele Bannister from the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada. "But almost all of these icy worlds are painfully small and faint: it's really exciting to find one that's large and bright enough that we can study it in detail."

RR245's huge orbit – which you can see in the image above – takes it about 700 years to circle the Sun, and the researchers say it's currently travelling in for its closest approach, which will see it get within 5 billion kilometres of the Sun sometime around 2096.

That's after spending hundreds of years at more than 12 billion kilometres from the Sun, although the team acknowledges there's still a lot to be confirmed about RR245's precise movements, as we've only been able to observe just a tiny fraction of its epic loop so far.

Scientists think there were once many more of these dwarf planets in our Solar System, but most were destroyed or ejected when the larger planets in our Solar System moved to their current positions. But now RR245 joins the ranks of other survivors from this period – such as Ceres, Pluto, Haumea, Makemake, and Eris, which have all been recognised as dwarf planets by the International Astronomical Union – amidst the tens of thousands of much smaller objects beyond Neptune.

The researchers first spotted the dwarf planet in February, when astronomer JJ Kavelaars from the National Research Council of Canada was sifting through OSSOS data recorded in September 2015.

"There it was on the screen," said Bannister, "this dot of light moving so slowly that it had to be at least twice as far as Neptune from the Sun."

The team suggests it's possible that RR245 may be one of the last large worlds detected beyond Neptune with today's telescopes, as the brightest dwarf planets have already been mapped – although the debut of the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope next decade could turn up new discoveries we haven't been able to detect so far.

"OSSOS was designed to map the orbital structure of the outer Solar System to decipher its history," said one of the researchers, Brett Gladman of the University of British Columbia in Canada. "While not designed to efficiently detect dwarf planets, we're delighted to have found one on such an interesting orbit."

But beyond helping us map the outer reaches of our Solar System, the discovery of these dwarf planets – and their unique geological composition – helps us understand more about the cosmic past in our corner of the galaxy.

"They are the closest thing to a time capsule that transports us to the birth of the Solar System," astrophysicist Pedro Lacerda from Queen's University Belfast in Northern Ireland, who wasn't involved with the discovery, told Ian Sample at The Guardian. "You can make an analogy with fossils, which tell us about creatures long gone."

The discovery hasn't been published yet, so we're still waiting on further details from the researchers for now, but RR245 has been formally noted by the International Astronomical Union.