Using the most detailed map of the galaxy produced so far, astronomers have spotted more than a dozen high-speed stars that seem to be zooming in our direction – and they are potentially just a fraction of the total number of stars on similar headings.

Interestingly, the study was intended to find high velocity stars heading out of the Milky Way; instead, the team ended up identifying more that were travelling in the opposite direction.

Such long-distance travelling stars could hold crucial clues to what lies out there in the furthest reaches of space, and the history of nearby galaxies.

When a star isn't gravitationally tied to the rotation of a galaxy, astronomers call it an unbound star.

The fastest of these types of stars - known as hypervelocity stars, travelling at speeds of up to 700 km/s (435 mi/s) - are thought to be flung out of the centre of the Milky Way after having a brush with the supermassive black hole in its middle. Only a small number of these have been discovered before now.

But while looking for potential new hypervelocity stars, the team from Leiden University in the Netherlands instead found a bunch of candidates for speedy, unbound cosmic bodies heading towards us - hyper-runaway stars.

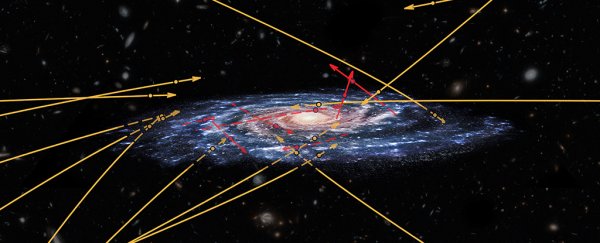

According to the researchers, some of these stars are shooting inwards from the galactic disc, but others could even be intergalactic visitors, coming from the Large Magellanic Cloud, or somewhere further afield.

"Rather than flying away from the galactic centre, most of the high velocity stars we spotted seem to be racing towards it," says one of the team, Tommaso Marchetti.

"These could be stars from another galaxy, zooming right through the Milky Way."

The discovery has been made possible by the most recent data dump from the European Space Agency's Gaia satellite, including information at an unprecedented level of accuracy on around 1.7 billion stars.

For seven million of the brightest of these stars, Gaia has logged 3D motion data as well as 2D plots, and from that sample the researchers were able to spot 20 new unbound high velocity star candidates. Seven of them appear to be travelling in from the galactic disc, and 13 can't be traced back to the Milky Way at all.

If these cosmic immigrants have indeed arrived from outside our galaxy, they could tell us about the characteristics of other galaxies we can't yet see, in the same way that falling meteorites give us a wealth of information about what's out there in deep space.

There are over 100 billion stars in the Milky Way, most arranged in the familiar disc shape you might have seen in pictures. As in other galaxies, at the centre of this dense disc is a supermassive black hole, which might explain some of these super-fast speeds.

"Stars can be accelerated to high velocities when they interact with a supermassive black hole," says one of the researchers, Elena Maria Rossi. "So the presence of these stars might be a sign of such black holes in nearby galaxies."

"But the stars may also have once been part of a binary system, flung towards the Milky Way when their companion star exploded as a supernova. Either way, studying them could tell us more about these kinds of processes in nearby galaxies."

We're going to need more data to know for sure, both from future Gaia measurements and from observations carried out by telescopes down here on Earth.

One alternative explanation put forward by the researchers is that they're from inside the Milky Way's halo – that falling remnants of dwarf galaxies within our own could explain the unusual way they're shooting through space. More data on the composition and age of the stars will help us know for sure.

"We eventually expect full 3D velocity measurements for up to 150 million stars," says one of the astronomers, Anthony Brown, who is also chair of the Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium Executive.

"This will help find hundreds or thousands of hypervelocity stars, understand their origin in much more detail, and use them to investigate the galactic centre environment as well as the history of our galaxy."

The study has been published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.