As far as stars go, SDSSJ013333 resembles the quiet kid in school nobody remembers. Small, dim, and unremarkable, it does little to gain attention. That is until it throws a whopping big tantrum.

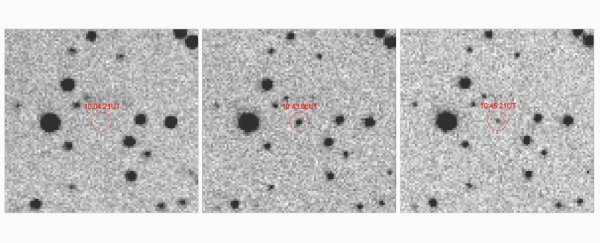

Days before 2018 drew to a close, the Ground-based Wide Angle Camera (GWAC) at Xinglong Observatory in Beijing alerted researchers to a burst of light worth paying attention to.

After hitting its peak in just under a minute, the entire event – a solar flare dubbed GWAC 181229A – lasted a matter of a few hours. But given where it came from, it would be one worth considering for the record books.

A flick through star catalogues quickly revealed SDSSJ013333 sulking on its own roughly 490 light-years away, so dark and distant the astronomers had a hard time pinning down exactly how far away it truly was. Not a star you'd expect to blast out something so bright.

SDSSJ013333 belongs to a category of stellar objects called ultra-cool dwarfs. Typically around a third of the mass of our own Sun, they have an effective temperature that's only half as hot, and a slow-burning furnace that can last hundreds of billions of years.

But although ultra-cool dwarfs might take things slow, every now and then their magnetic fields snap and reconnect in ways that see them erupt with tremendous bursts of radiation and plasma.

We're not talking a tiny roasting either. Thanks to the brilliance of many such emissions, these flares can only be described as super.

Usually, superflares are the work of youngsters, especially the slightly warmer red dwarfs. One from a red dwarf was caught by a Japanese research team last year, measuring roughly 20 times as powerful as anything seen coming out of our Sun.

But the flare put out by ultra-cool SDSSJ013333 let one rip that would put most to shame.

Typically measured in a unit of energy called an erg (from an old Greek word for work, ergon), a typical flare might put out around 10^30 ergs. Superflares can reach up as high as around 10^36 ergs.

Astronomers estimated SDSSJ013333 released just over 10^34 ergs of energy; an insane effort for such a cold-hearted star, and possibly among the largest ever recorded for one in its particular class.

To put it another way, the flare briefly made the star 10,000 times brighter, taking its magnitude from just over 24 down to a more dazzling 15. Not something we'd see with the naked eye, but bright enough for a good telescope to capture.

The researchers have made their results available on the pre-publish arXiv database for public perusal, where we can read their take on it while it awaits peer review.

As remarkable as the event is, it's only in context of other flares that we can learn how ultra-cool dwarfs – which make up around 15 percent of all stellar objects in our corner of the galaxy – form and develop.

"Thanks to the large field of view and the high survey cadence, GWAC is well-suited for the detection of white-light flares. Actually, we have hitherto detected more than 130 white-light flares with an amplitude more than 0.8 mag," the team reports.

"More GWAC units are planned to work in the next two years, aiming to increase the detection rate of high-amplitude stellar flares by monitoring more than 5,000 square degrees simultaneously."

That's a lot of space. But we'll need to cast a wide net to see what else is lurking out in our galaxy.

Having solid evidence of what these stars are capable of ejecting can help astronomers better understand the physics churning away beneath their surface.

It also has implications for the possibility of life around these stars.

One ultra-cool dwarf turned celebrity in recent years is TRAPPIST-1. Found to be surrounded by an extensive family of exoplanets – some of which are in a zone that could make them damp with liquid water – it was once speculated as a hot spot for future alien hunters.

That was all until astronomers did the sums on how often TRAPPIST-1 might bake its brood of tiny worlds in a sterilising tsunami of high energy solar wind.

Similarly, if SDSSJ013333 was home to an alien paradise before, chances are slim we'd find much standing there now.

This research was published on arXiv.org.