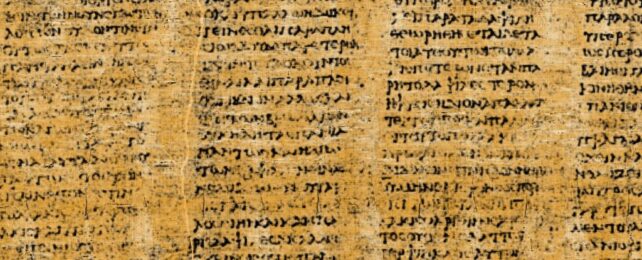

The great libraries of the ancient classical world are legendary. From Alexandria to Rome to Athens, Baghdad, and Constantinople, these vast archives of times gone by are said to have contained stacks of texts on religion, politics, philosophy, poetry, literature, and the sciences.

Only one's collection has survived to the present day, and we can now start reading its contents.

A worldwide competition to decipher the charred texts of the Villa of Papyri – an ancient Roman mansion destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius – has revealed a timeless infatuation with the pleasures of music, the color purple, and, of course, the zingy taste of capers.

The so-called Vesuvius challenge was launched a few years ago by computer scientist Brent Seales at the University of Kentucky with support from Silicon Valley investors. The ongoing 'master plan' is to build on Seales' previous work and read all 1,800 or so charred papyri from the ancient Roman library, starting with scrolls labeled 1 to 4.

In 2023, the annual gold prize was awarded to a team of three students, who recovered four passages containing 140 characters – the longest extractions yet. The winners are Youssef Nader, Luke Farritor, and Julian Schilliger.

"After 275 years, the ancient puzzle of the Herculaneum Papyri has been solved," reads the Vesuvius Challenge Scroll Prize website.

"But the quest to uncover the secrets of the scrolls is just beginning."

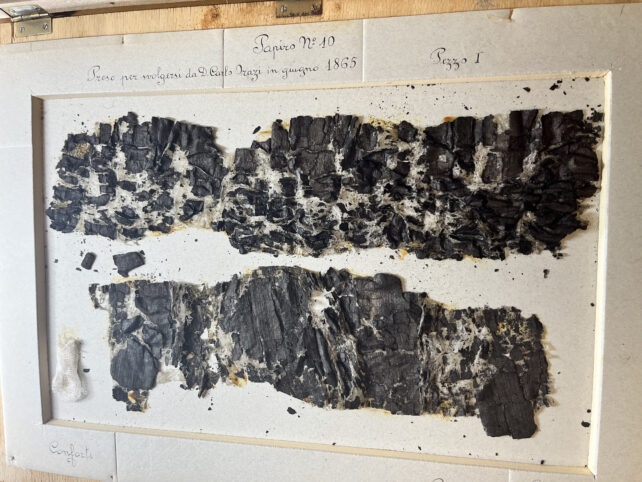

By looking at one of these charcoaled cylinders today, it's hard to imagine how anyone could actually read one.

Indeed, no one could manage it for centuries.

The blackened, rolled-up documents were first unearthed in the city of Herculaneum in the mid-18th century. They had been buried under 20 meters (66 feet) of 'cement' after a massive wall of hot volcanic mud and ash pummeled the city in 79 CE.

Against the odds, many of the scrolls survived. They were carbonized to a crisp, but because they were buried away from the decaying effects of air, they were also remarkably preserved.

Given their extremely fragile state, which some scientists compare to a butterfly's wings, many scrolls were unfortunately destroyed in past unfurlings, as can be seen below.

Only now, with the advent of X-ray tomography and machine learning, can their inky words be pulled from the darkness of carbon.

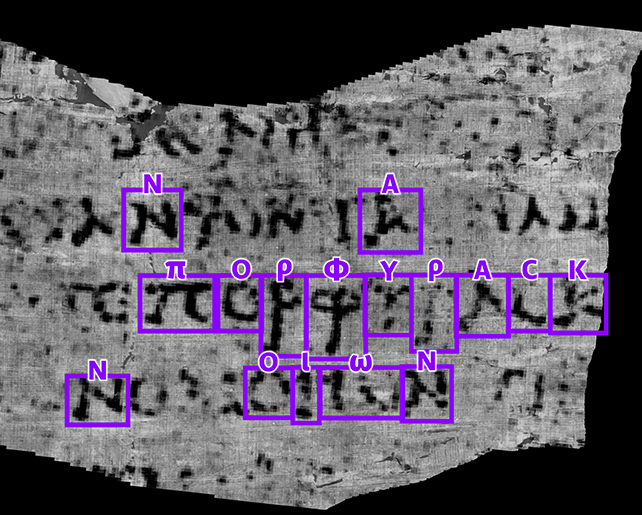

In October of 2023, officials of the Vesuvius Challenge announced that the first letters had been gleaned from a Herculaneum scroll.

Two students had separately trained the artificial intelligence software, first put together by Seales, to identify strokes of ink. Their work highlighted the word "πορϕυρας" (or "porphyras" using modern Greek characters), which means 'purple'.

That winning code was then made available for all competitors to build upon.

Within three months, passages in Latin and Greek were blooming from the blackness, almost as if by magic.

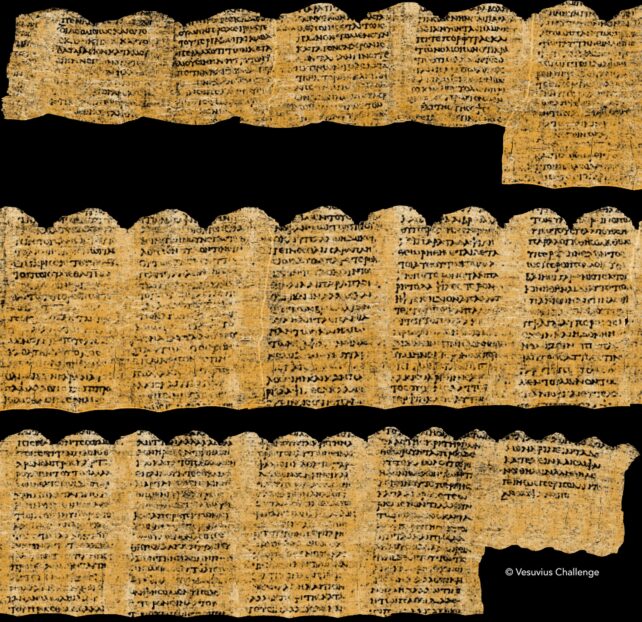

The team with the most readable submission at the end of 2023 included both previous finders of the word 'purple'.

Their unfurling of scroll 1 is truly impressive and includes more than 11 columns of text. Experts are now rushing to translate what has been found.

So far, about 5 percent of the scroll has been unrolled and read to date. It is not a duplicate of past work, scholars of the Vesuvius Challenge say, but a "never-before-seen text from antiquity."

One line reads: "In the case of food, we do not right away believe things that are scarce to be absolutely more pleasant than those which are abundant."

Another reads: "… for we do [not] refrain from questioning some things, but understanding/remembering others. And may it be evident to us to say true things, as they might have often appeared evident!"

According to scholars from the Vesuvius Challenge, "the general subject of the text is pleasure, which, properly understood, is the highest good in Epicurean philosophy. In these two snippets from two consecutive columns of the scroll, the author is concerned with whether and how the availability of goods, such as food, can affect the pleasure which they provide."

Classicist Richard Jenko from the University of Michigan thinks the author of the text may be a follower of Epicurus, as someone of that description is thought to have lived and worked at the Villa of Papyri.

"Is the author Epicurus' follower, the philosopher and poet Philodemus, the teacher of Vergil? It seems very likely," Jenko writes for the challenge website.

"Is he writing about the effect of music on the hearer, and comparing it to other pleasures like those of food and drink? Quite probably. Does this text come from his four-part treatise on music, of which we know Book 4? Quite possibly: the title should soon become available to read."

Because some of the passages contain Latin text and others are written in ways that are quite poetic or broad in content, scholars of the Vesuvius Challenge are holding out for "an Aristotle dialog, a lost history of Livy, a lost Homeric epic work, a poem from Sappho" or other, much-desired texts.

This is one ancient library from classical antiquity that we can one day hope to peruse.