A major volcanic cataclysm may have been ultimately responsible for the spread of the Black Death across Europe in the 1340s.

In a lovely example of scientific investigation at its best, researchers pieced together multiple lines of evidence to reveal what appears to have been a volcanically induced climate micro-crisis – and showed how it influenced trade and travel, bringing plague pathogens to just the wrong moment in time and space.

It was a perfect storm of conditions that could have unleashed the world's second plague pandemic, resulting in the deaths of millions of people across the European continent.

Related: The Black Death Shaped Human Evolution, And We're Still in Its Shadow

Peaking in the middle of the 1300s, the Black Death is widely regarded as one of the most devastating events in human history, claiming tens of millions of lives across the world.

It was caused by the Yersinia pestis bacterium and transmitted to humans via fleas, leading to plague, a disease that can be fatal within a day in its most severe forms.

There's a lot we still don't know about how it kicked off and spread. One open question is whether the bacterium remained in Europe since the first plague pandemic, which began with the Plague of Justinian in 541 CE, or whether it was reintroduced from outside the continent.

A new analysis by historian Martin Bauch of the Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe in Germany and paleontologist Ulf Büntgen of the University of Cambridge in the UK favors the latter explanation – one that aligns with very recent evidence that the second plague emerged in Kyrgyzstan and spread along trade routes.

To figure out how the plague made its way from the high-altitude mountains of Central Asia to the warm seaports of the Mediterranean, Bauch and Büntgen studied cores extracted from ice of Antarctica and Greenland, analyzed tree ring data from eight regions across Europe, and investigated 14th-century European accounts of the weather conditions they experienced.

The ice cores provide the strongest physical evidence of a volcanic eruption occurring at a critical moment in history. Snapshots of the atmosphere's composition at the time the ice was deposited as snow preserve an exceptionally detailed record of past climate and major volcanic events.

Cores from the middle of the 14th century revealed a massive spike in sulfur levels coinciding with snow deposited around 1345 CE – an ice core signature almost always associated with a major volcanic eruption. They also found smaller sulfur spikes in 1329, 1336, and 1341 CE, but the 1345 spike is notable – the 18th largest such spike in the last 2,000 years.

Next, the researchers examined tree-ring data. Every year, more or less, trees add a layer to their trunks, and subtle changes in that growth – especially in the density of the latewood – reflect how warm or cool the growing season was.

In 1345, 1346, and 1347, temperature reconstructions based on these rings from eight regions across Europe show a run of unusually cold summers, with the signal particularly strong around the Mediterranean.

This is a classic hallmark of a massive eruption: a volcano blasts sulfur-rich gases into the stratosphere, where they form a veil of sulfate particles that reflects sunlight and cools the planet for a few years. That short-term cooling can be enough to disrupt growing seasons and devastate crop cycles, leading to famines.

Finally, historical accounts from across Europe and Asia report conditions consistent with volcanic activity, including fog and hazy skies; exceptionally cold, wet summers; and harvest failures.

All the pieces of the puzzle appear to fit. An unidentified volcano, likely somewhere in the tropics, underwent a massive, violent eruption in 1345. The climate cooled; crops failed; grain prices skyrocketed; and famine hit Spain, southern France, northern and central Italy, Egypt, and the Levant.

The plague reached Italy in 1347, the same year Venice lifted its trade embargo on the Golden Horde, and grain shipments flowed in from across the Black Sea.

Previous research has found that fleas carrying Y. pestis could easily have survived these voyages.

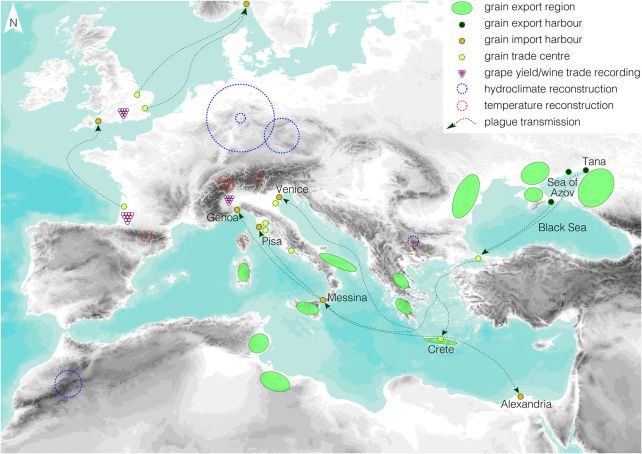

The first European outbreaks of plague occurred in the ports receiving these shipments: Messina, Genoa, Palma, Venice, and Pisa. As the grain was distributed across the country, the plague it carried spread.

This wasn't limited to Europe. Plague also likely arrived via grain ships to Alexandria across the Mediterranean in Egypt. A map of plague dispersal in the paper shows the pathogen later moving from Mediterranean grain ports northward into the English Channel and the North Sea, reaching the coasts of England and Norway along established maritime routes.

The research is one of those remarkable pieces of multidisciplinary detective work that slots all the clues into place to build a comprehensive timeline, hundreds of years later.

"We used climate proxy and written documentary archives to argue that a yet unidentified volcanic eruption, or a cluster of eruptions around 1345 CE, contributed to cold and wet climate conditions between 1345 and 1347 CE across much of southern Europe," the researchers write.

"This climatic anomaly and subsequent transregional famine forced the Italian maritime republics of Venice, Genoa, and Pisa to reconfigure their supply network and import grain from the Mongols of the Golden Horde around the Sea of Azov in 1347 CE.

"The unusual change in long-distance maritime grain trade prevented large parts of Italy from starvation and distributed the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis via infected fleas in grain cargo across much of the Mediterranean basin, from where the second plague pandemic emerged into the largest mortality crisis in pre-modern times."

The research has been published in Communications Earth & Environment.