Might brain damage linked to Alzheimer's be one of the reasons dolphins lose their way and end up stranded? It's a possibility explored in a new study of 20 common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) stranded in the Indian River Lagoon, Florida, between 2010 and 2019.

What's more, the researchers behind the study have linked the signs of dolphin neurodegeneration to climate change – via toxic blooms of algae and bacteria that are becoming more frequent and widespread in warmer waters.

An analysis of the brains of the stranded dolphins revealed changes to gene expression that are associated with Alzheimer's in humans, as well as damage typical of the disease, like clumped proteins.

Related: Fat Buildup in Brain Cells Could Provide New Target For Alzheimer's Treatment

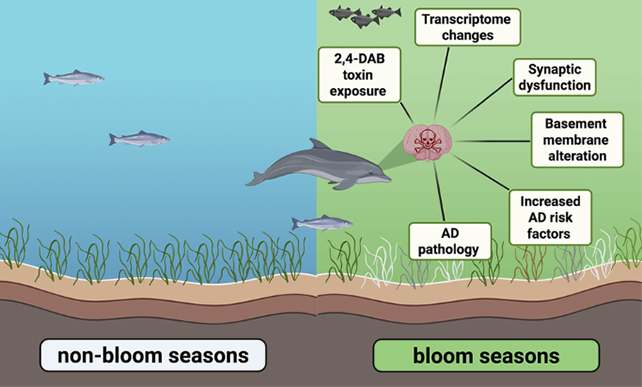

There was a significant difference in the dolphins stranded during algal bloom seasons though: Their brains showed levels of the neurotoxin 2,4-diaminobutyric acid (2,4-DAB) that were a whopping 2,900 times more concentrated than in other dolphins that beached themselves when no algal blooms were around.

It's evidence of the harmful effects of blooms filled with cyanobacteria, and it could explain some of the loss of navigational skills and memory that would lead these dolphins to become stranded.

"Since dolphins are considered environmental sentinels for toxic exposures in marine environments, there are concerns about human health issues associated with cyanobacterial blooms," says toxicologist David Davis, from the University of Miami.

For context, it's important to note that dolphins normally develop brain problems that look a lot like Alzheimer's as they get older. We also know that toxins given off by cyanobacteria can harm neurons in animals and people, though links to human neurodegenerative diseases are still under investigation.

The suggestion the team is making now is that these problems might be accelerated and made worse in dolphins by harmful algal blooms. The study adds details on the neurotoxins doing the damage, the key consequences in the dolphin brains, and the seasonal variations.

"The co-occurrence of Alzheimer's disease neuropathological changes and the natural accumulation of algal toxins observed in dolphins allows a unique opportunity to study the impact of these two converging events on the brain," write the researchers in their published paper.

The risks aren't just limited to dolphins, either: these blooms are causing harm to plenty of other kinds of marine life, which then has knock-on effects going up the food chain, leading eventually to humans.

Past research has already linked algal blooms to toxins that can lead to memory loss, which is of course a key characteristic of Alzheimer's. If these chemicals get into our food in large enough amounts, that could be a serious problem.

This study looks at dolphins and not humans, but some of the fundamental, Alzheimer's-like shifts in the brain are the same, the researchers note. There's no direct link yet, but the signs are there, and that's at least worthy of further investigation.

Some of the same researchers have previously looked at cyanobacteria and the neurotoxins they produce in cycad trees, finding that these toxins can persist in the environment and can accumulate up the food chain. That's a potential pathway where exposure to these toxins might lead to different types of neurodegeneration in human beings, including dementia.

"Although there are likely many paths to Alzheimer's disease, cyanobacterial exposures increasingly appear to be a risk factor," says Davis.

The research has been published in Communication Biology.