Scientists have grown small but complex models of human organs from live fetus cells for the first time, giving experts new insight into our development and potential treatments for malformations while in the womb.

These organoids aren't full replicas of organs, but they're close enough to the real deal that they can be used to study disease and other aspects of human biology that are difficult to investigate in living people.

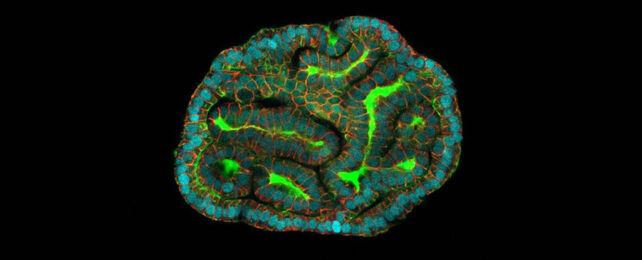

In a new study carried out by an international team of researchers, lung, kidney, and intestine organoids were grown from living stem cells in amniotic fluid. This fluid helps to protect the growing baby and feed it with nutrients, and is taken from the mother without harming her baby as part of regular pregnancy tests.

"The organoids we created from amniotic fluid cells exhibit many of the functions of the tissues they represent, including gene and protein expression," says biologist Mattia Gerli, from University College London (UCL) in the UK.

"They will allow us to study what is happening during development in both health and disease, which is something that hadn't been possible before."

Organoids have previously been grown from the cells of terminated fetuses, which comes with ethical concerns and tight regulation restrictions. They can also be grown from adult stem cells, but this is much later in the body's development.

What the new tissue potentially gives scientists is a way of studying problems in the womb, many weeks before the baby is born. Plenty of further study will be needed to get to that stage, but it's something that we're now closer to doing.

In particular, the team looked at congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH), which can lead to respiratory problems. By examining organoids grown from fetuses with and without CDH, the researchers were able to track down any genes linked to the condition, informing potential future treatments.

"This is the first time that we've been able to make a functional assessment of a child's congenital condition before birth, which is a huge step forward for prenatal medicine," says Paolo de Coppi, a consultant pediatric surgeon at UCL.

"Diagnosis is normally based on imaging such as ultrasound or MRI and genetic analyses. When we meet families with a prenatal diagnosis, we're often unable to tell them much about the outcome because each case is different."

This opens a potential avenue for treating a condition before it even develops significant consequences.

Drugs that are developed for congenital diseases such as cystic fibrosis could be tested on organoids before being given to unborn babies, the researchers say. It's a window into fetal development that we didn't have before.

That the study authors were successful in identifying the types of cells in the amniotic fluid and develop these mini organs is a major and promising step forward – but there's still lots of work to do.

"We know so little about late human pregnancy, so it's incredibly exciting to open up new areas of prenatal medicine," says Gerli.

The research has been published in Nature Medicine.