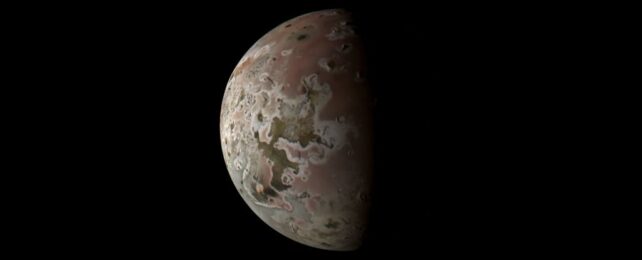

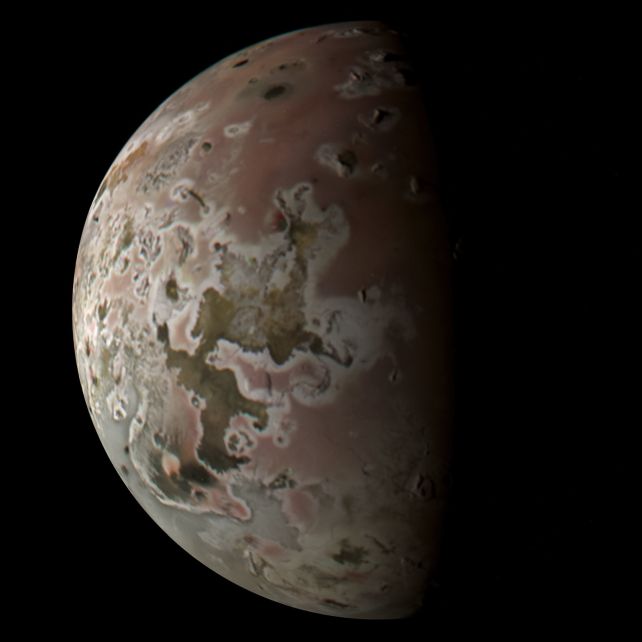

The scarred and sulfurous surface of the most volcanically active body in the Solar System has just appeared in spectacular new images from Jupiter probe Juno.

The NASA spacecraft flew by Jupiter's moon Io on 15 October, swooping in as close as just 11,680 kilometers (7,260 miles) from the hellish surface. The new images showcase the moon's north polar region, and even captured some volcanic plumes from ongoing eruptions.

Given an estimated 150 or so of the 400-ish known volcanoes on Io are erupting at any given time, this is not necessarily a huge surprise, but it is pretty neat to be able to see the moon in action.

Scientists are saying that these images are the best and clearest we've had of Io since Jupiter probe Galileo, which studied the gas giant and its moons between 1995 and 2003.

"Images such as these will provide Io research with plenty of analysis work for years to come," writes Jason Perry of the University of Arizona, formerly of the Galileo mission, who processed some of the raw images. "They cover Io's anti-Jovian hemisphere before going over Io's north polar region and settling out over the satellite's sub-Jovian hemisphere."

Io is a fascinating object. The innermost Jovian moon is just a little bit bigger than Earth's Moon, and absolutely bristling with volcanoes. Infrared images show it speckled with heat as molten material from below the surface surges up, creating vast lakes of lava.

This is because of its hectic gravitational environment. Io's orbit around Jupiter is an ellipse, which means the gravitational influence of Jupiter varies, changing the shape of the moon as it orbits. And the other Galilean moons – Callisto, Europa, and Ganymede – all exert their own gravitational pull on Io. This creates frictional heating in the tiny moon that melts its insides, which then spew out everywhere all over the surface.

The effect this has is tremendous. The constant stream of sulfur dioxide gas erupting forth from Io is ripped out into Jupiter's orbit, where it forms a huge torus of plasma that gets constantly diverted and accelerated along the giant planet's magnetic field lines.

When it reaches the poles, this material falls down into Jupiter's atmosphere, interacting with the material therein to generate permanent ultraviolet aurorae – invisible to the naked eye, but the most powerful in the Solar System. Io is proof that you don't gotta be big to make a mark.

The new images reveal new details of the moon's north polar region, which has non-volcanic mountains reaching up to 6,000 meters (20,000 feet) in height. Because it's non-volcanic, it doesn't change as much over time as some of the more active regions.

Around the edge of the disk, at least two volcanic plumes have been captured, too. There may be more to be found as the images are cleaned up and processed.

And Juno's not even done yet. The probe will be conducting spectacularly close flybys in the coming months; on 30 December 2023 and 3 February 2024, it is slated to swoop in as close as 1,500 kilometers (930 miles) from the surface of Io. We can't wait to see the photos.