Compared to Earth, the Moon doesn't have much going on. Where our planet's surface features an impressive mix of windswept plains, ice-carved ravines, and volcanic mountain peaks, the lunar surface has impact craters. Lots of impact craters.

Earth's satellite is pocked and scarred from being pummeled with space shrapnel over billions of years, without the dynamic geological and atmospheric processes that keep our world's face relatively fresh.

But it's not all ancient history. The Moon's bombardment is ongoing, and the rain of debris is constant.

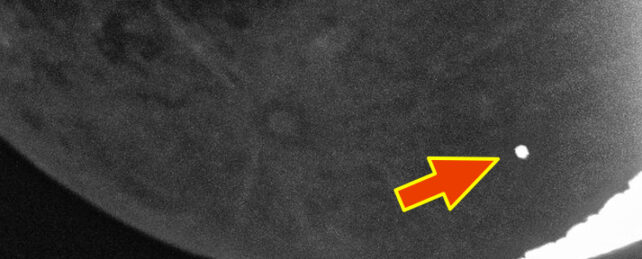

Most of it goes unseen, but a particularly bright impact flash was caught by astronomer Daichi Fujii of the Hiratsuka City Museum in late February, using Moon-viewing equipment at his home in Hiratsuka.

Most objects in space are too small and dark to be seen as they approach the Moon, so we only know they've hit from the impact flash. In order to capture one, you need to be looking at exactly the right time – so astronomers hoping to see an impact set up monitoring equipment to ensure they don't miss a moment.

"I was able to catch the biggest lunar impact flash in my observation history!" Fujii wrote on Twitter.

"This is a picture of the lunar impact flash that appeared at 20:14:30.8 on February 23, 2023, taken from my home in Hiratsuka (replayed at actual speed). It was a huge flash that continued to shine for more than 1 second. Since the moon has no atmosphere, meteors and fireballs cannot be seen, and the moment a crater is formed, it glows."

私の観測史上最大の月面衝突閃光を捉えることができました!2023年2月23日20時14分30.8秒に出現した月面衝突閃光を、平塚の自宅から撮影した様子です(実際の速度で再生)。なんと1秒以上も光り続ける巨大閃光でした。月は大気がないため流星や火球は見られず、クレーターができる瞬間に光ります。 pic.twitter.com/Bi2JhQa9Q0

— 藤井大地 (@dfuji1) February 24, 2023

Actually, the fact the Moon is under constant bombardment shouldn't come as a huge surprise. Near-Earth space is peppered with small rocks, a number of which tumble into our planet's atmosphere daily. A 2020 study estimated that some 17,600 rocks with masses greater than 50 grams fall every year.

The reason why they typically don't make the news is the thick layer of gas they're forced to pass through usually robs them of any fanfare. Meteors falling through Earth's atmosphere tend to burn up or explode without our knowing; what doesn't vaporize eventually hits the ground as much smaller rock pieces, or dust that doesn't leave a significant mark… never mind an impact crater.

The Moon doesn't have an atmosphere, and meteors travel fast. Consider a rock hitting Earth's atmosphere at speeds up to 72 kilometers (45 miles) per second. Anything that slams into the Moon's surface is going to slam hard.

2023年2月23日20時14分30.8秒の月面衝突閃光を、別の望遠鏡で捉えた様子です(実際の速度で再生)。このとき月の高度はわずか7度で、ぎりぎりまで粘ってよかったです。観測時のTLEで月面を通過する人工衛星はなく、光り方からも月面衝突閃光の可能性が高いです。 pic.twitter.com/GqG8CkYeRr

— 藤井大地 (@dfuji1) February 24, 2023

Most of what hits is going to be pretty small. We're not going to see it even with a telescope. But a few years ago, a project by the European Space Agency designed to study lunar impacts using more powerful technology found that objects big enough to create a flash hit the Moon, on average, 8 times an hour.

Among those frequent collisions will be an occasional impact from a larger object, one visible with backyard equipment. It doesn't have to be a huge rock, either. In 2019, an astronomer caught a lunar impact flash during a lunar eclipse; the estimated size of that rock was around 2 kilograms (4.4 pounds), about the size of a football.

We won't know more about Fujii's impact until follow-up observations are taken. The size of the crater should help astronomers calculate the size and speed of the object that caused it; which information, in turn, will help better characterize the constant hail of rocks slamming into our satellite, and the evolution of its craggy, pitted surface.