For humans, getting whacked in the face by heavy raindrops is a mere annoyance. But for tiny and delicate organisms - like butterflies - drops of rainwater are the equivalent of a person being pummelled by bowling balls falling from the sky. Ouch.

"[Getting hit with] raindrops is the most dangerous event for this kind of small animal," said biological and environmental engineer Sunghwan "Sunny" Jung, from Cornell University in New York.

Jung explains that the force of impact alone isn't the only problem raindrops can cause for fragile living things. Rain wreaks havoc on insects' flight momentum and can strip birds of their warmth, so limiting time in contact with each raindrop is critical for many animals.

Seungho Kim, Jung and colleagues took a closer look at how different animals and plants mitigate this potential danger. They used a high-speed camera capturing between 5,000 and 20,000 frames per second to observe the impact of water falling onto butterflies, moths, dragonflies, gannet feathers, and katsura leaves.

Previous studies had made similar observations on drop impacts at speeds much lower than real raindrops - which can reach up to 10 metres (33 feet) per second. In this new study the team dropped water on their subjects at high speeds, and recorded the different impact dynamics that came into play.

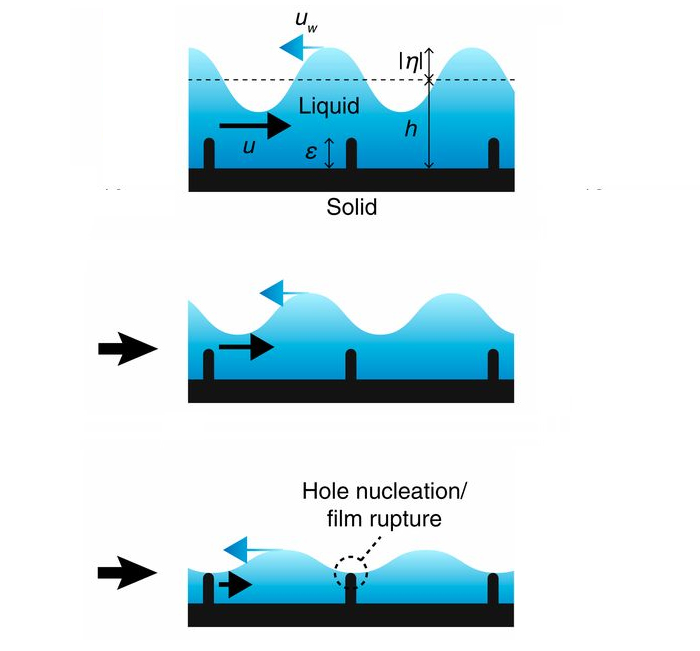

They observed that as a drop collides with the surface of a leaf or a butterfly wing, it falls onto microscopic bumps or spikes that create shock-like waves through the miniature body of water. These waves interfere with each other, causing the droplet to form a wrinkled pattern as it spreads, with different thicknesses across its volume.

Then, just as the drop is about to bounce away, the wave effect allows the spikes on the surface of the wing to poke holes right through the water film, which ruptures the drop into tiny fragments. (This effect was further investigated by dropping water onto an artificial surface that mimicked the surface spikes.)

Diagram of post-impact rippling drop on super-hydrophobic surface. (Kim et al, PNAS, 2020)

Diagram of post-impact rippling drop on super-hydrophobic surface. (Kim et al, PNAS, 2020)

A nanoscale-structured wax layer on these natural surfaces helps to repel the water; this, along with the fragmentation of the drop, reduces the contact time between liquid and surface by up to 70 percent, the researchers found.

In turn, that reduces the amount of heat and momentum transfer. This would make a huge difference for insects who need to retain some warmth in their muscles to be able to fly and escape predators.

"By having these two-tiered structures - one microscale (the rough bumpy structure) and the other nanoscale (the wax structure)," explains Jung, these organisms "can have a super hydrophobic [water-repelling] surface."

(Cornell University)

(Cornell University)

Kim and colleagues also caught these fragmented rain shards smuggling pathogenic fungal spores - revealing how fungi can use plant defences to enhance their own dispersal powers.

"This is the first study to understand how high-speed raindrops impact these natural hydrophobic surfaces," said Jung.

This enhanced understanding of how micro-spikes on butterfly wings shatter raindrops could help engineers to develop more advanced waterproofing materials, an area which has already drawn from nature, like the water-repelling coating on clothes that's inspired by lotus leaves.

"There's a huge market for these kinds of surfaces," said Jung, but if you want to make "engineering products inspired by this material, durability is the biggest issue."

This research was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.