Silicon has had a very good run as the material upon which all of our electronics are based, but it's starting to reach its limits. Now there's a new contender for running our computers and smartphones: carbon nanotubes.

Scientists just made the largest working computer chip to date out of this hugely promising material. And it could represent the start of an entirely new kind of computing revolution.

As silicon transistors (the devices that carry the 1s and 0s of computers) start to bump up against the limits of physics in terms of size and density, the evidence so far points to carbon nanotubes being a faster and more energy efficient option.

Processors (lots of transistors packed together) made from carbon nanotubes could help computing take the next leap forward.

In this new study, researchers used rolled up sheets of carbon, each a single atom thick, to form 14,000 carbon nanotube field-effect transistors (CNFETs) – up from a previous attempt in 2013 that managed 178 transistors.

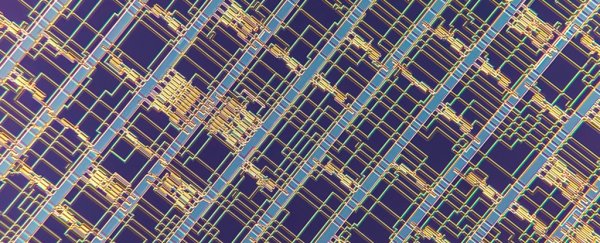

(MIT)

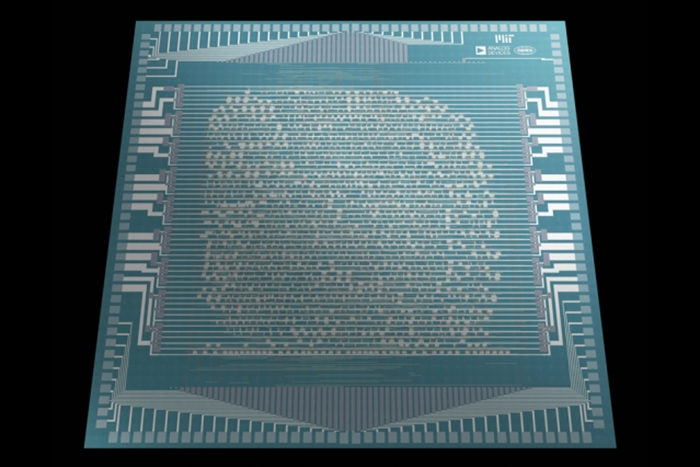

(MIT)

"This is by far the most advanced chip made from any emerging nanotechnology that is promising for high-performance and energy-efficient computing," says computer scientist Max Shulaker, from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

"There are limits to silicon. If we want to continue to have gains in computing, carbon nanotubes represent one of the most promising ways to overcome those limits. [The paper] completely reinvents how we build chips with carbon nanotubes."

The 16-bit processor (the more bits, the more complexity) was even functional enough to run a basic program, producing the words "Hello, World! I am RV16XNano, made from CNTs" (Carbon Nanotube Transistors).

What's even more impressive is that the previous attempt at a chip involved only one a single bit.

While carbon nanotubes have a lot of potential, manufacturing them into transistors is a real challenge. That's due to defects in the material that mean some CNFETs don't keep their semiconductor properties (the ability to conduct a current when voltage is applied), while others 'clump together' and impair the workings of the processor.

Both these problems were overcome by the researchers. One of the fixes involved working out circuit designs that wouldn't be affected by any CNFETs not semiconducting as they should be, allowing a little more room for error in the manufacturing processes.

Currently, the material used in these chips requires 99.999999 percent purity, which is virtually impossible. The new technique only requires 99.99 percent purity, which still sounds high, but is actually 10,000 times less.

While the team tweaked various parts of the manufacturing process, including adding an oxide compound layer, much of the processor construction process is the same as it is with silicon, and that bodes well for eventually replacing silicon with carbon nanotubes.

"This work takes a big step forward and gets much closer to a commercial chip," physicist Yanan Sun from the Shanghai Jiao Tong University in China, who wasn't involved in the research, told Nature.

These are promising times for computer scientists looking to explore a world of machines that go beyond the limitations of silicon – finding a replacement for silicon is also an important part of developing practical quantum computers.

We're not all the way there yet though: what we're seeing here is a proof-of-concept that hasn't yet been proved to be faster or more energy efficient than a comparable silicon processor. The team admits there's plenty of room for improvement.

However, 14,000 transistors is a major step up from 178 transistors, and with the improvements made to the manufacturing process, the researchers reckon these chips could be viable within five years.

"We think it's no longer a question of if, but when," says Shulaker.

The research has been published in Nature.