If there's one thing we know about SARS-CoV-2, is that its effects on people vary. A lot. As the pandemic rolls on, this coronavirus continues to bring new surprises.

A team of researchers and doctors has now reported the case of one woman with leukemia who had no symptoms of COVID-19 but 70 days after her first positive test, she was still shedding infectious SARS-CoV-2 particles.

This result is much longer than previous reports of hospitalised adults found shedding infectious SARS-CoV-2 virus up to 20 days after their COVID-19 diagnosis, plus other accounts of people shedding genetic material from the virus up to 63 days after their symptoms first appeared.

The new report should alert doctors and public health experts alike to the fact that people without symptoms and with weakened immune systems, such as cancer patients, can seemingly shed the SARS-CoV-2 virus for a really long time. In this case, even months.

"Although it is difficult to extrapolate from a single patient, our data suggest that long-term shedding of infectious virus may be a concern in certain immunocompromised patients," the research team wrote in their paper describing the case.

An estimated 3 million people in the US have some kind of condition that compromises or weakens their immune system, making them vulnerable to infections. Cancer patients on chemotherapy and transplant recipients who take immunosuppressant drugs are some examples.

"As this virus continues to spread, more people with a range of immunosuppressing disorders will become infected, and it's important to understand how SARS-CoV-2 behaves in these populations," said virologist and co-author Vincent Munster from the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Virologists like Munster would have been on the lookout in this pandemic for prolonged viral shedding of SARS-CoV-2. It has been well established that immunocompromised people can shed common seasonal coronaviruses for weeks after infection.

Studies of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) have likewise shown immunocompromised people shedding the virus that causes this illness for up to one month after infection.

But the proportion of asymptomatic COVID-19 cases still remains unclear. The danger is that these carriers of the virus could easily go about their days unaware of their capability of spreading the virus.

In this case, doctors detected, isolated and tracked one woman's SARS-CoV-2 infection using diagnostic PCR tests and throat swabs. A decade ago, the 71-year-old woman was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), a cancer of white blood cells that most commonly affects older adults and progresses slowly.

She first tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on 2 March 2020 after she was admitted to hospital for severe anaemia related to her cancer. She then tested positive for COVID-19 another 13 times and yet showed no symptoms of the disease.

Twice she received plasma from people who had recovered from COVID-19, and eventually cleared the virus from her system sometime in mid-June.

Doctors don't know exactly when she acquired the coronavirus, but most likely it was at a rehabilitation facility which had a large COVID-19 outbreak in February, where the woman had stayed days earlier.

From the throat swabs collected over the course of her 15-week infection, the researchers showed that the woman was shedding infectious SARS-CoV-2 particles for 70 days. Some of its genetic material was also detected up to 105 days after she first tested positive.

We have to be careful here to distinguish between infectious viral particles and the results of a diagnostic test, which just detects shreds of viral RNA. Importantly, in this study the researchers actually isolated SARS-CoV-2 from a few swab samples – day 70 included – to test whether the virus collected was able to replicate in lab-grown cells, which it was.

"This indicates that, most likely, the infectious virus shed by the patient would still be able to establish a productive infection in contacts upon transmission," the researchers wrote.

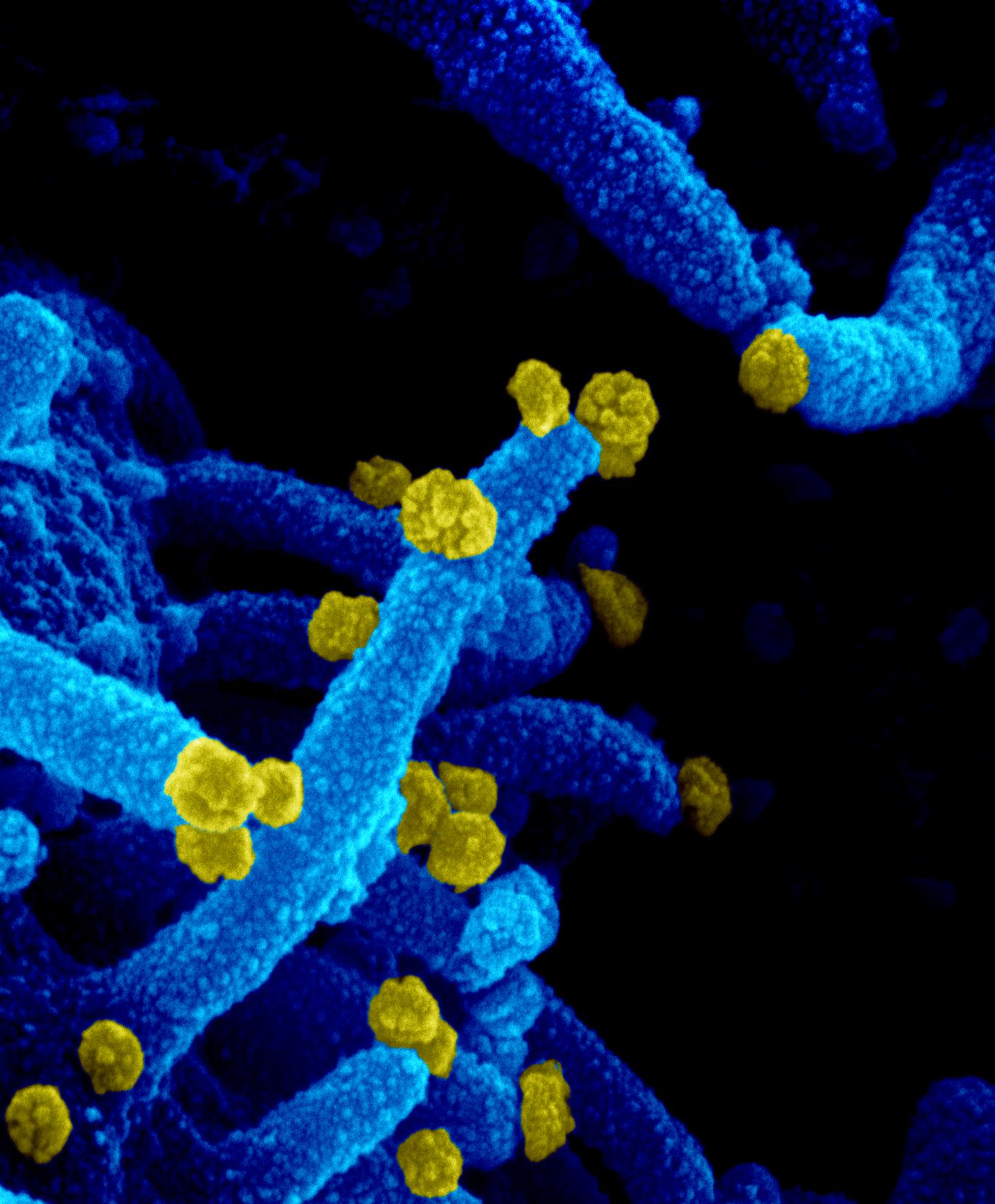

SARS-CoV-2 particles obtained from the woman's throat swab and cultured in lab-grown cells. (NIAID-RML)

SARS-CoV-2 particles obtained from the woman's throat swab and cultured in lab-grown cells. (NIAID-RML)

Additionally, once the doctors were alerted to the woman's case, they also quickly recognised it as an opportunity to study how SARS-CoV-2 might evolve over the course of such a long infection.

The researchers sequenced the virus' genetic material from various samples to see how this particular SARS-CoV-2 virus changed while circulating through the woman's body. Different viral variants became more dominant at certain times, but the turnover was high and none stuck.

Further experiments with the isolated virus in lab-grown cells also showed that these genetic changes didn't affect how fast the virus replicated.

While these are some valuable insights, more research still needs to be done.

"Understanding the mechanism of virus persistence and eventual clearance will be essential to providing appropriate treatment and preventing transmission of SARS-CoV-2, as persistent infection and prolonged shedding of infectious SARS-CoV-2 occur more frequently," the study authors wrote in their paper.

And yes, this is a single case study, so we can't make any generalisations about persistent viral shedding in people with other immunocompromising conditions, or how effective convalescent plasma is as a treatment for COVID-19, the study authors warn.

It is, however, "the longest case of anyone being actively infected with SARS-CoV-2 while remaining asymptomatic," according to the medical research team. They think the woman remained infectious for so long because her compromised immune system never allowed her to mount a response.

"We've seen similar cases with influenza and with Middle East respiratory syndrome, which is also caused by a coronavirus," Munster said. "We expect to see more reports like ours coming out in the future."

With each one, we'll surely learn more about this virus, how long it persists, and what we need to do to take care of the most vulnerable people in our communities.

The study was published in the journal Cell.